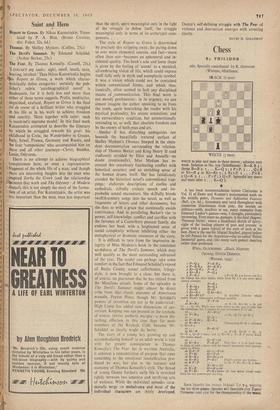

Saint and Hero

Thomas. By Shelley Mydans. (Collins, 25s.) The Fear. By Thomas Keneally. (Cassell, 25s.)

`I COLLECT my tools: sight, smell, touch, taste, hearing, intellect: Thus Nikos Kazantzakis begins 'leis Report to Greco, a work which charac- teristically defies categories: certainly the pub- lisher's rubric 'autobiographical novel' is inadequate, for it is both less and more than either of those terms suggests. Prolix, meditative, anguished, exultant, Report to Greco is the final cti de coeur of a brilliant writer who struggled in his life as in his work to achieve freedom and sanctity. `Hero together with saint: such is mankind's supreme model.' In this final work Kazantzakis attempted to describe the itinerary by which he struggled towards his goal: his childhood in Crete, the Wanderjahre in Greece, Italy, Israel, France, Germany and Russia, and the four 'companions' who accompanied him on these and all other journeys—Christ, Buddha, Lenin, Odysseus.

There is no attempt to achieve biographical completeness here, or even a representative fragment of the whole life of a man; and though there are interesting insights into the man who Inspired Zorba the Greek (and the relationship ' between that work and The Odyssey : A Modern Sequel), this is not simply the story of the forma- tion of an artist. For Kazantzakis, the artist was less important than the man, man less important

than the spirit, spirit meaningful only in the light of the struggle to define itself, the struggle meaningful only in terms of its archetypal com- ponents. . . .

The style of Report to Greco is determined by precisely this stripping away, the paring down to ever more elemental sources, and fact—more often than not—becomes an ephemeral and in- cidental quality. The book's sole and loose shape is given by the feeling of `ascent' to a mystical, all-embracing vision of life, which could express itself fully only in myth and esemplastic symbol. It was a vision which could not be contained within conventional forms, and which thus, ironically, often seemed to lack any disciplined means of .communication. This final work is not merely posthumous: in its urgency, we can almost imagine the author speaking to us from the tomb, again bewitching the reader with his mystical profundity, his ornate sensualism, and his extraordinary erudition, but unintentionally reminding us, as well, that absolute freedom can be the enemy of both man and art.

Similar if less disturbing ambiguities rest beneath the beautifully textured surface of Shelley Mydans's Thomas. Steeped in the abun- dant documentation surrounding the relation- ship of Thomas Becket and King Henry II (and studiously avoided by Eliot and Anouilh—no doubt intentionally), Miss Mydans has re- created this ceaselessly fascinating conflict with historical accuracy and an enriching sense of the human drama itself. She has fastidiously avoided the historical novel's conventional trap- pings: elaborate descriptions of castles and cathedrals, stiltedly archaic speech and im- probable sexual encounters. She skilfully blends twelfth-century songs into the novel, as well as fragments of letters and other documents, but she does so with a grace that continually avoids contrivance. And in paralleling Becket's rise to power, self-knowledge, conflict and sacrifice with the fortunes of a Canterbury peasant family, she endows her book with a heightened sense of social complexity without inhibiting either the metaphysical or dramatic resources of the story.

It is difficult to turn from the impressive in- tegrity of Miss Mydans's book to the consistent sordidness of The Devil's Summer, which may well qualify as the most outstanding sub-novel of the year. The reader can perhaps take some comfort in the fact that Edmund Schiddel's exposé of Bucks County sexual callisthenics, trilogy- style, is now brought to a close, but there is, of course, no guarantee that he has retired from the Metalious circuit. Some of the episodes in The Devil's Summer might almost be direct cribs from that classic anatomy of Americana sexualis, Peyton Place, though Mr. Schiddel's powers of invention are not to be underrated: High Camp has added new dimensions of per- version. Keeping one eye pressed to the keyhole, of course, invites aesthetic myopia—a more dis- turbing affliction in this case than for most members of the Keyhole Club, because Mr. Schiddel so clearly might do better.

The story of a young boy growing up and accommodating himself to an adult world is told with far greater consequence in Thomas Keneally's The Fear. Set in wartime Australia, it achieves a concentration of purpose that owes something to the emotional intensification pro- duced by war, but also to the tautness and economy Of Thomas Keneally's style. The thread of young Danny Jordan's early life is stretched tightly between two senseless and terrifying acts of violence. While the individual episodes occa- sionally verge on melodrama and most of the individual characters are thinly developed. Danny's self-defining struggle with The Fear of violence and destruction emerges with arresting clarity.

DAVID D. GALLOWAY

Previous page

Previous page