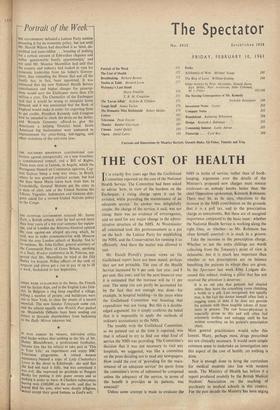

THE COST OF HEALTH

IT is exactly five years ago that the Guillebaud Committee reported on the cost of the National Health Service. The Committee had been asked to advise 'how, in view of the burdens on the Exchequer, a rising charge upon it can be avoided, while providing the maintenance of an adequate service.' Its answer was delightfully simple; the charge of the service, it said, was not rising; there was no evidence of extravagance, and no need for any major change in the admin- istrative structure of the NHS. At Westminster all concerned took this pronouncement as a pat on the back : the Labour Party for establishing the NHS, and the Conservatives for running it so efficiently. And there the matter was allowed to rest.

Mr. Enoch Powell's present views on the Guillebaud report have not been stated; perhaps they are not printable. The cost of the Health Service increased by 6 per cent. last year, and 8 per cent. this year; and for the next financial year it is estimated that the increase will be 11 per cent. The steep rise can partly be accounted for by the fact that not enough was done—for example, in hospital building—in the years when the Guillebaud Committee was boasting that expenditure was not rising. But this is a double- edged argument; for it simply confirms the belief that it is impossible to apply the methods of ordinary accountancy to the NHS.

The trouble with the Guillebaud Committee, as we pointed out at the time it reported, was that it refused to try to find out what kind of service the NHS was providing. The Committee's decision that it was not necessary to visit any hospitals, we suggested, was like a committee on the press deciding not to read any newspapers. How could the cost of 'providing for the main- tenance of an adequate service' (to, quote from the committee's terms of reference) be computed unless the adequacy of the service, in terms of the benefit it provides to its patients, was assessed?

Unless some attempt is made to evaluate the NHS in terms of service, rather than of book- keeping, arguments over the details of the Minister's proposed new charges must remain irrelevant—as nobody knows better than the chief Opposition spokesman, Kenneth Robinson. There may be, as he says, objections to the increase in the NHS contribution on the grounds that it is a poll tax, and to the prescription charge as uneconomic. But these are of marginal importance compared to the basic issue: whether the National Health Service is working along the right lines, or whether—as Mr. Robinson has often himself asserted—it is stuck in a groove.

Take the increase in the prescription charge. Whether or not the extra shillings are worth collecting from the Treasury's point of view is debatable; but it is much less important than whether or not prescriptions are on balance benefiting the patients to whom they are given. In the Spectator last week John Lydgate dis- cussed this subject, making a point that has not received the attention it deserves: It is an old joke that patients feel cheated unless they leave the consulting room clutching a bottle or a pill. Less recognised, but equally true, is the fact the doctor himself often feels a nagging sense of debt if he does not provide his patients with these tangible tokens of treat- ment in process. The raw house-physician is especially prone to this and will often feel extremely restless and unhappy until he has written something on his patient's prescription chart.

Most general practitioners would echo this lament. Many, perhaps most, drugs prescribed are not clinically necessary. It would seem simple common sense to undertake an investigation into this aspect of the cost of health; yet nothing is done.

Nor is enough done to bring the curriculum for medical students into line with modern needs. The Ministry of Health has before it a report produced recently by the British Medical Students' Association on the teaching of psychiatry in medical schools in this country. For the past decade the Ministry has been urging the public to study the ugly fads of mental illness, including the now familiar one that almost half the hospital beds in this country are occupied by mental patients. But what is the use of explain- ing these things to the public, if the profession ignores them? The BMSA report shows that many medical schools have simply not begun to regard the teaching of psychiatry as part of their job; in some 'teaching' hospitals all that medical students arc given on the subject is a short course of lectures—no experience in wards or in out-patient departments at all. If the profes- sion cannot train medical students to deal with the diseases we have, then it is time it stepped aside and let some other organisation take on the job.

By concentrating on the value for cost, rather than the cost of health, the Minister has a chance to show himself as enlightened as he is already known to be courageous. There is a widely prevalent belief, shared by his own Ministry, that the medical profession is the best judge of the country's health needs—which is like saying the Army is the best judge of the country's defence needs. The medical profession today is run by men who are still in the cavalry era; they cannot see that their strategy is directed against the enemies of the last war but one. Somebody will have to take them and shake them; and by an unusual piece of good fortune, it is hard to think of anybody among the Conservative Ministers who is better able to perform that unenviable task than Enoch Powell.

Previous page

Previous page