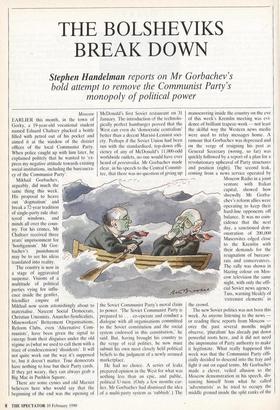

THE BOLSHEVIKS BREAK DOWN

Stephen Handelman reports on Mr Gorbachev's

bold attempt to remove the Communist Party's monopoly of political power

Masco w EARLIER this month, in the town of Gorky, a 19-year-old vocational student named Eduard Chaltsev plucked a bottle filled with petrol out of his pocket and aimed it at the window of the district offices of the local Communist Party. When police caught up with him later, he explained politely that he wanted to 'ex- press my negative attitude towards existing social institutions, including the bureaucra- cy of the Communist Party'.

Mikhail Gorbachev, arguably, did much the same thing this week. His proposal to heave out 'dogmatism' and break a 72-year tradition of single-party rule shat- tered windows, and minds all over the coun- try. For his crimes, Mr Chaltsev received three years' imprisonment for 'hooliganism'. Mr Gor- bachev's punishment may be to see his ideas translated into reality.

The country is now in a stage of aggravated suspense. Visions of a multitude of political parties vying for influ- ence inside the gentler, friendlier empire of Mikhail now seem astonishingly about to materialise. Nascent Social Democrats, Christian Unionists, Anarcho-Syndicalists, Mineworkers' Betterment Organisations, Reform Clubs, even 'Alternative Com- munists', have been given the signal to emerge from their disguises under the old regime as (what we used to call them with a trace of condescension) 'dissidents'. It will not quite work out the way it's supposed to, but it doesn't matter. True democrats have nothing to lose but their Party cards. If they get weary, they can always grab a Big Mac in Pushkin Square.

There are some cynics and old Marxist believers here who would say that the beginning of the end was the opening of

McDonald's first Soviet restaurant on 31 January. The introduction of the technolo- gically perfect hamburger proved that the West can even do 'democratic centralism' better than a decent Marxist-Leninist soci- ety. Perhaps if the Soviet Union had been run with the standardised, top-down effi- ciency of any of McDonald's 11,0(N)-odd worldwide outlets, no one would have ever heard of perestroika. Mr Gorbachev made clear, in his speech to the Central Commit- tee, that there was no question of giving up

the Soviet Communist Party's moral claim to power. 'The Soviet Communist Party is prepared to . . . co-operate and conduct a dialogue with all organisations committed to the Soviet constitution and the social system endorsed in this constitution,' he said. But, having brought his country to the verge of real politics, he now must submit his own most closely held political beliefs to the judgment of a newly aroused marketplace.

He had no choice. A series of leaks prepared opinion in the West for what was nothing less than an epic, and public, political U-turn. (Only a few months ear- lier, Mr Gorbachev had dismissed the idea of a multi-party system as 'rubbish'.) The manoeuvring inside the country on the eve of this week's Kremlin meeting was evi- dence of brilliant trapeze-work — not least the skilful way the Western news media were used to relay messages home. A rumour that Gorbachev was depressed and on the verge of resigning his post as General Secretary (wrong, so far) was quickly followed by a report of a plan for a revolutionary upheaval of Party structures and position (right). The second leak, coming from a news service operated by Moscow Radio in a joint venture with Italian capital, showed how shrewdly Mr Gorba- chev's reform allies were operating to keep their hard-line opponents off balance. It was no coin- cidence that the next day, a sanctioned dem- onstration of 200,000 Muscovites edged close to the Kremlin with their demands for the resignation of bureauc- rats and conservatives. The rally was shown in blazing colour on Mos- cow television the same night, with only the offi- cial Soviet news agency, Tass, warning bleakly of 'extremist elements' in the crowd.

The new Soviet politics was not born this week. As anyone listening to the news or reading these reports from Moscow over the past several months might observe, 'pluralism' has already put down powerful roots here, and it did not need the imprimatur of Party authority to make it legitimate. What really happened this week was that the Communist Party offi- cially decided to descend into the fray and tight it out on equal terms. Mr Gorbachev made a clever, veiled allusion to the Moscow demonstration in his speech, dis- tancing himself from what he called 'adventurists' as he tried to occupy the middle ground inside the split ranks of the leadership. But everyone is aware that there is no longer any middle ground.

At its most important levels, in district and republic headquarters, the Party is in terminal disarray. Entire Party organisa- tions have been kicked out of office over the past several weeks in dozens of central Russian cities. Among the most humiliat- ing blows was the expulsion of Yuri Solovyev, a former Leningrad Party chief and member of the Politburo, when a local television programme revealed that he had used his influence to buy a Mercedes car for the price of a second-hand Russian one. The chaos in the non-Russian republics is already well documented.

The apparatchiks apparently did not know, or would not believe, the distaste with which they were regarded everywhere in the homeland of the working class, A public opinion poll conducted in December showed 86 per cent of Party members wanted a `drastic' purge in upper Party ranks. Only ten per cent had responded positively to the idea six months before.

One recent incident in the town of Chernigov illustrates the point. Two cars collided in the middle of the town. One of them, a black Volga operated by a city official, turned over, spilling its contents on to the road. Passers-by saw an unbeliev- able assortment of canned goods and con- sumer items, none of which was available in local shops. The next day an angry crowd marched on the main square. Most townspeople expect there won't be a Com- munist Party official left after the local elections scheduled later this month.

Mr Gorbachev knew these facts and many others before he decided to open the door to genuine political struggle in his country. But he also cannot fail to be aware of the darker side of what such a struggle entails. Among the `factions' emerging into the sunlight of Soviet demo- cracy are Russian chauvinists, Stalinists, anti-semites, militarists, monarchists and a multitude of others who are united in their distrust of the West and everything Mr Gorbachev stands for. The Soviet leader in tact was probably right when he said months ago that the Soviet Communist Party was the only organisation strong enough to hold the country together and ensure its body politic did not disintegrate into a seething, anarchic mass.

His decision roughly to force the Party Out of its privileged cocoon was a measure of the frustration triggered by events over the past 12 months. Just before the plenum opened, Mr Gorbachev met with a group of 100 miners from the regions which had gone on strike last summer. They told him bluntly, 'It's time you made clear whose side you were on.' The Soviet leader looked at them with surprise. 'You mean, it wasn't clear?' he asked. Now, for better or worse, it is.

Stephen Handelman is Moscow bureau chief of the Toronto Star.

Previous page

Previous page