Dance

Romeo and Juliet (Royal Opera House)

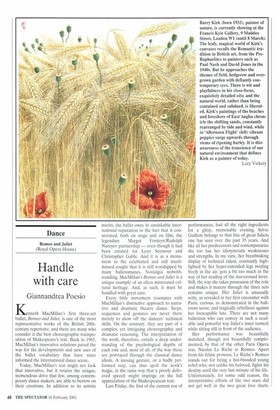

Handle with care

Giannandrea Poem

Knneth MacMillan's first three-act ballet, Romeo and Juliet, is one of the most representative works of the British 20thcentury repertoire, and there are many who consider it the best choreographic transposition of Shakespeare's text, Back in 1965, MacMillan's innovative solutions paved the way for the developments and new uses of the ballet vocabulary that have since informed the international dance scene.

Today, MacMillan's text might not look that innovative, but it retains the unique, tremendous drive that few, among contemporary dance makers, are able to bestow on their creations. In addition to its artistic merits, the ballet owes its unsinkable international reputation to the fact that it consecrated, both on stage and on film, the legendary Margot Fonteyn/Rudolph Nureyev partnership — even though it had been created for Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable. And it is as a monument to the celebrated and still muchmissed couple that it is still worshipped by many balletomanes. Nostalgia notwithstanding, MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet is a unique example of an often mistreated cultural heritage. And, as such, it must be handled with great care.

Every little movement resonates with MacMillan's distinctive approach to narrative and dramatic theatre dance. Steps, sequences and gestures are never there merely to show off the dancers' technical skills. On the contrary, they are part of a complex, yet intriguing choreographic and dramatic reasoning. The interpretation of the work, therefore, entails a deep understanding of the psychological depths of each role and, most of all, of the way these are portrayed through the classical dance idiom. A missing gesture, or a badly performed step, can thus spoil the work's magic, in the same way that a poorly delivered speech might impinge on the full appreciation of the Shakespearean text.

Last Friday, the first of the current run of

performances, had all the right ingredients for a glitzy, memorable evening. Sylvie Guillem belongs to that line of great Juliets one has seen over the past 35 years. And like all her predecessors and contemporaries she too has her idiosyncratic weaknesses and strengths. In my view, her breathtaking display of technical talent, constantly highlighted by her hyper-extended legs twirling freely in the air, gets a bit too much in the way of her reading of the star-crossed lover. Still, the way she takes possession of the role and makes it mature through the three acts remains unique. Her Juliet is unusually witty, as revealed in her first encounter with Paris; curious, as demonstrated in the ballroom scene, and tragically rebellious against her inescapable fate. There are not many ballerinas who can convey in such a readable and powerful way Juliet's inner turmoil while sitting still in front of the audience.

Her performance was beautifully matched, though not beautifully complemented, by that of the other Paris Opera star, Nicolas Le Riche as Romeo. Apart from his feline prowess, Le Riche's Romeo stands out for being a hot-blooded young rebel who, not unlike his beloved, fights his destiny until the very last minute of his life. Unfortunately, for some odd reason, the interpretative efforts of the two stars did not gel well in the two great love duets. The sparkling passion and the tense drama of the two love scenes were thus replaced by a rather uninspiring, lukewarm display of balletic mannerism with no trace of chemistry between them whatsoever. One can only hope that things will get better once the two artists have had more chances to get in tune with each other.

As Mercutio, Johan Persson has opted for a noble reading instead of turning his role into the jester-like figure most of his colleagues favour rather erroneously. Persson, however, has yet to discover the subtle undertones other great noble interpreters, such as Egon Madsen, used to enrich the part. The detrimental effects of such a cool-blooded approach become fully evident, alas, in the death scene, one of the most unmoving and uninspiring I have ever seen.

There was a lack of dramatic depth also in the amazingly non-villainous Tybalt of William Tuckett who, like Persson, should take some lessons in how to die effectively on stage.

Previous page

Previous page