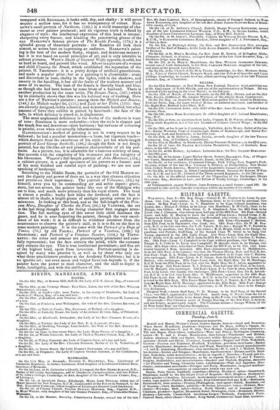

FINE ARTS.

ANCIENT AND MODERN PICTURES AT THE BRITISH INSTITUTION.

THE selection of pictures by the Old Masters and by deceased English painters, at the British Institution, affords striking proofs of the infe-

riority of the modern manner of painting as compared with the method

adopted by Sir JOSHUA REYNOLDS, the founder of the British school, and by the great masters of other schools. The North Room is wholly filled by the works of Sir Josnoz, to the number of sixty, including many of his most famous pictures: and a magnificent display of por- traiture it is ; equally remarkable for strength of character in the drawing and power and splendour of colouring. The South Room contains specimens of several English painters of various periods, from COPLEY, HOGARTH, and GAINSBOROUGH, to JACKSON, NEWTON, and LAWRENCE; a medley of styles, in which no two observe the same method, and nearly all—so far as the mere process of painting is concerned— appear to be wrong. The Middle Room is devoted to the Old Masters ; and, although the selection is meagre, it embraces a few very fine por- traits, which demonstrate that the principles on which they proceeded were understood and observed by one English painter at least.

Our present purpose being to point out the difference between the modern and ancient manner of painting, as exemplified in this exhibi- tion, we shall mention only such pictures as subserve to this object, Passing by, therefore, the Laughing Girl, Sleeping Girl, Strawberrt Girl, Piping Boy, Snake in the Grass, and other studies of rustics character by REYNOLDS—which, the Strawberry Girl excepted, are more admirable for sentiment and effect than the method of painting-- we turn to his portraits. In looking round at these noble productions of art, we feel as if standing in the living presence of the men whose intellectual and personal characteristics have been perpetuated by the pencil : thus stood Rodney and Keppel on the quarter-deck—so sat Camden on the woolsack. The bald head and round features of the Marquis of Granby, familiar as they are to us in the numerous engrav- ings, appear in the canvass of REYNOLDS endowed with traits of Indi- viduality not before noted. The portrait of Lord Camden, (23,) is ex- traordinary for the rapidity and vigour with which it is painted : it is a sketch, seemingly dashed off at a sitting, and afterwards heightened by a few spirited touches. Compare this slight and hasty work with an elaborate portrait of the same learned man by DANCE, (169,) where the curls of the wig, the lace lappets, and the damask curtain vie with the head and hands in importance—and in hardness : the oae is a "staring likeness," all substance and detail, without animation ; the other lives and breathes and thinks, though little more than a suggestive indication. REYNOLDS aimed at portraying the character of the man as shown in the expression of his countenance at a particular moment, and has succeeded, with only a few hours' work : DANCE en- deavoured to imitate every article of dress to illusion, and has failed even in that, after months of labour ; the lappets and wig look more real than the face—though their appearance is not such as it would have been when seen in connexion with other parts of the costume—and in proportion as they seem "palpable to feeling as to sight" the head becomes a lifeless clod : for there is no imitating the breath. REYNOLDS'S portrait of Lord Camden, however, is not a model for the student ; it is a wonderful sketch, not a completely finished picture. His own portrait of Himself, (6,) and that of Sir William Chambers, (15,) are worthy to be studied, equally for design, colour, and that appearance of rotundity which is wanting in the works of contemporary artists. These two fine portraits belong to the Royal Academy ; and as they hang among the Diploma-pictures presented by successive Academicians on their elec- tion, strong though silent is their rebuke of the falliog-off in the British school of painting. The unfinished portrait of Dr. Johnson, (54,) the head of which has been left uncoloured, is an example of the "dead colouring" which REYNOLDS used in his more elaborate works, at one period of his career—for his mode of painting varied, and he tried ex- periments in different ways. Nor was he equally successful at all times, either in the modelling of the form in light and shade or in the after painting : the vehicle of his pigments was often too thick, and cracked ; and his colouring sometimes overpowered the light and shade, so as to destroy or lessen the appearance of rotundity : but whatever he did was characterized by force of effect and richness of colour. How poor and fiat the portraits of Sir THOMAS LAWRENCE look after those of Ray- MOLDS ! they appear like imitations in oil-colour of crayon paintings. That of Mrs. Allnutt, (1800 is only a mask; head there is none : and Vis- countess Palmerston when a Child, (145,) is a mere film of paint. nom- NElet3 Portrait of the late Lord Farnborough, (l63,) and The late Duke of Grafton, (175,) too, are very flimsy. JAessores celebrated Portrait cf Flarnuut, (146,) which made such a sensation in the Academy Exhibi- tion some twelve or fourteen years ago, is an excellent likeness, strongly impressed with living character, and an admirable work of art; yet

compared with REYNOLDS, it looks cold, dry, and chalky : it will never acquire a mellow tone, for it has no transparency of colour. Hen:

LOWE'S small portrait of Northcote, (123,) is a vivid transcript of cha-

racter as ever painter produced ; and its vigorous truth is refined by elegance of style: the intellectual expression of this head is intense ; sharpening every feature, and kindling the penetrating glance of the

eye. Heru.owe's famous picture of The Kemble Family, (178,) is a splendid group of theatrical portraits : the Kembles all look their

utmost, as actors bent on impressing an audience. HARLOWE'S paint- ing is the best of the modern flashy, elegant, and dexterous manner ; but it is not based on sound principles of art, and is only tolerable in

cabinet pictures. WEST'S Death of General Wolfe, opposite, is solid, but as hard as board, and painted like wood. Above is a picture of a woman and child Crossing the Brook, which established the reputation of the painter, H. THOMPSON : it is a pretty design of artificial gracefulness, and made a popular print; but as a painting it is abominable : crude and discordant it tone, chalky in the lights, cold in the shadows, and smeary in the handling, it has all the faults of the modern manner and none of its merits. The bust of the female is literally black and blue, as though she had been beaten by some brute of a husband. There is another production by the same artist, The Roman Nurse, (167,) which by its similarity shows that this was his habitual way of daubing. Here are a few of NEWToN'S pictures ; among them the Shyloch and Jessica, (148,) Le Malade malgri lui, (153,) and Lady at her Toilet, (155): they are cleverly designed,richly coloured, and dexterously handled, but what amount of force they exhibit is gained by heaviness : the face of the lady, in which delicacy is aimed at, is diaphonous. The most unpleasant deficiency in the works of the moderns is want of tone : flimsiness is more endurable-when the style is elegant and the touch free and dexterous-than hardness ; but rawness of colouring is painful, even when not actually inharmonious.

GAINSBOROUGHS method of painting is not in every respect to be followed ; he bad a peculiar mannerism-a loose, but vigorous touch- which detracts from the excellence of his style : yet his whole-length portrait of Lord George Sackville, (186,) though the flesh is not firmly painted, has the life-like air and presence characteristic of all his por- traits. As a picture, too, it is admirable for a lustrous sobriety of tone, that accords with the simplicity of his treatment and the integrity of his likenesses. WILSON'S full-length portrait of John Mortimer, (162,) a cabinet picture, is a good specimen of his powers as a limner, and of his most finished and careful style of painting : we are not now speaking of landscape. Returning to the Middle Room, the portraits of the Old Masters as- sert the dignity and power of their art in a way that silences objection and proclaims their supremacy. The portrait of Velasguez, (83,) by himself, awes you by its commanding air and noble aspect: grave, stern, but not severe, the painter looks like one of the Hidalgos who sat to him, and much more princely than his royal sitters. The head is almost a profile; bushy hair hides the forehead, and the face is almost all in shade, a bright gleam of sunlight passing across its pro- minences. In looking at this head, and at the full-length of the Prin- cess Mary, Daughter of Charles the First, (96,) by VANDYKE, the art is the last thing thought of: the living character first engages atten- tion. The full melting eyes of this sweet little child fascinate the gazer, and he is near forgetting the painter, through the very excel- lence of his work : it is as difficult to withdraw attention from the countenance to observe the painter's skill, as it is to fix on the face in some modern paintings. It is the same with the Portrait of a Doge of Venice, (79,) by old Ruble; Portrait of a Venetian, (100,) by GIORGIONE ; and Portrait of a Venetian Senator, (104,) by TINTO- RETTo : the robes and armour are picturesquely prominent and care- fully represented ; but the face attracts the mind, while the costume only attracts the eye. This is true intellectual portraiture ; and fine art of the highest kind, apart from invention. Portrait-painting is de- spised by many who practise it, as well as by those who only see what those practitioners produce at the Academy Exhibition ; but it is no ignoble art : not even mean and vulgar faces can degrade it, if the painter have the power to read character, and the skill to depict it truly, intelligibly, and with the attributes of life.

Previous page

Previous page