Theatr e

Something Blue

By ALAN BRIEN

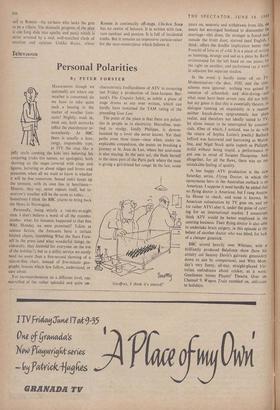

Tomorrow — With Pic- tures! (Lyric, Ham- , mersmith.) — The Caretaker. (Duchess.) — Don't Shoot—We're English. (Cambridge.) — Chicken Soup With Barley. (Royal Court.) ONE thing that perhaps ought to be made clear about Tomorrow—With Pictures! and yet has not been sufficiently stressed by other reviewers, is that it makes an extra- ordinarily comic evening. The dialogue is a Palimpsest of witticism, a mosaic of wisecracks, cemented with a cynicism so corrosive and ob- sessional that it shrivels every character who attempts to tread its crazy paving. The jokes rain down like confetti--something old, some- thing new, something borrowed, and something blue, especially something blue. It is impossible to believe that the Lord Chamberlain caught some of the innuendoes which kept a hip audience hiccoughing with glee on the second night. The idiom is early Ben Hecht sharpened by a little late Osborne. All the dialogue is written on the assumption that the brightest talkers are always (a) drunk and (b) lying down. Flexing their vocal cords at the horizontal bar, the players fire Otl. epigrams ('Having a child is like having a drunken house-guest for life'), anecdotes ('Did I tell you about Moishe who seduced his psycho- analyst with a deliberately falsified sexual his- tory? The analyst committed suicide but Moishe is a well man today'), repartee ('Don't man- handle me—I'm married.' That's all right. He can watch'), insults ('Who put the saccharine in her formaldehyde?') and insights (Don't forgive

makes me look ridiculous'). Groucho Marx versus Eve Arden, Oscar Wilde occasion- ally intervening: for three hours everyone is very knowing, nasty, glib, self-conscious and funny. Frankly, after a week of comedies in which the author treated me like a wine-logged business- man in an afternoon strip-club, I was grateful for this much.

But Tomorrow—With Pictures! is also in- tended to be a play about a cannibal queen of American journalism who eats the thing she loves and belches her disappointment through the London press club. It would be unkind (as well as unwise) to hazard a precise identification but the type is immediately recognisable. She wields her sex appeal like a blow torch, wears her talents like a bikini, and her success is always a form of suicide. I did not find Irene Dailey's Playing of this role so overwhelming as some critics did—she is a graduate corn laude of the same school as such other blonde lionesses as Elaine Stritch, Geraldine Page and Kim Stanley. But her strident good looks, her cheer-leader lung development, and her professional intelligence are unusual on the British stage. She deploys all

three with superb generalship to capture the role from the inside.

The weakness of the play lies in the failure of the authors, Anthony Creighton and Bernard Miller, to rescue this central character from what appears to be the ruins of a three-volume novel. She stalks through a maze of plots. bumping into underdeveloped situations and stunted theses at every corner, only to remain marooned in the centre at the final curtain. The impression of bittiness is strengthened by the authors' nervous habit of sending up each serious climax with a barrage of jokes, and of dodging each emotional denouement with a complete volte-face in style. Despite a ludicrously unlikely press conference in the opening scene, Tomorrow—With Pictures! has many penetrating comments to make about journalism. Stripped of its tinsel and pared of its irrelevancies. with less convulsive direction and fewer characters, this could be a satirical comedy which is worth taking seriously.

Harold Pinter's earlier plays were visions of life as an aquarium—each character swimming lonely in his separate tank, soundlessly mouthing his autobiography to neighbours who could neither hear nor feel his message. The Caretaker is a courageous act of vandalism. He has broken the glass and mixed the piranas with the guppies and the oysters. The failure of communication is often deadening, he suggests, but the success of communication is nearly always fatal. His people hear only too clearly the thoughts behind the words and feel only too painfully the hate behind the smile. They nuzzle close for the illu- sion of warmth, then burst apart in a flurry of panic at the first flash of teeth or snap of a shell. Mr. Pinter is gradually unmasking himself with his characters. The Caretaker still contains some cheating where the camouflage is worn for theatrical effect rather than dramatic point. But, as I see it, there is not a symbol in the house— simply three people embalmed alive in language

as specimens of us. It also contains three superb performances. What more dare one ask?

I asked only a little from Don't Shoot—We're English. I asked for tough satire from without, not cosy kidding from within. I asked for some contrast between deliberate mistakes of stage management and accidental blunders of Night at the Opera proportions. I asked for choreo- graphy based on more than three of Jerome Robbins's mannerisms—the invisible pistol shot, the bent paws bunny run, and the Hallelujah arms spread. I asked for some consciousness that the existence of urine is not nature's most hilari: ous hoax. Three sketches are enormously funny. For the rest, Michael Bentine not only doesn't know the answers, he cannot hear the questions.

Arnold Wesker's trilogy opened at the Royal Court with Chicken Soup With Barley. Later I hope to be able to discuss the three plays together, but for the moment I would merely like to sug- gest that the first contains all this brilliant young writer's faults and not all of his virtues. It is a provocative, moving, irritating, revealing muddle of a play. His East End Jewish family are psychic cripples, personally, socially and racially, who hide their wounds behind the collective neurosis of Communism. Part of the muddle is political, as if Mr. Wesker were writing a play about life in an asylum before he had been completely discharged. Old emotions are still stuck to new convictions, naïve assumptions melt into intellec- tual analyses.

The author's prefatory note in the printed text clearly spotlights the confusion—'Chicken Soup was not written as an anti-Soviet play and the author insists that no theatrical, film, television, or broadcasting company should present it as such. He would further remind all concerned that an indictment against the Inquisition is no more an attack on Christianity than an indictment based on recent Soviet admissions is an attack on Socialism. Let no mud be thrown; few people's hands are clean. Just let us think again.' Mr. Wesker has felt again rather than thought again. At the end, Sara, the Mother Courage of Mile End, who remains a Communist, is the only strong, true, humane, whole person in a family of cowards, failures and deserters. Part of the muddle seems to be personal. Mr. Wesker's honesty will not allow him to romanticise him-

self in Ronnie—the un-hero who lacks the guts to be a villain. The dramatic progress of the play is one long slide into apathy and panic which is never arrested by a real, well-matched clash of emotion and opinion. Unlike Roots, where Ronnie is continually off-stage, Chicken Soup has no centre of balance. It is written_ with raw, rare candour and passion. It is full of incidental truths. But it remains an impressive curtain-raiser for the near-masterpiece which follows it.

Previous page

Previous page