ARTS

Petipa's masterwork restored

Giannandrea Poesio welcomes the 'new' Kirov production of The Sleeping Beauty The presence of a Russian ballet com- pany has become a regular feature of the London dance scene in summer. This year we are in for a double treat. The historical- ly illustrious Kirov Ballet, now under the enlightened directorship of Makhar Vaziev, will have two seasons, the mid-June and the late July/August ones at the Royal Opera House instead of the usual one-off run of performances. The bag of choreo- graphic goodies which the Russians are bringing to London is thus particularly rich and varied. Performances of the unsink- able 19th-century classics will alternate with 20th-century-based programmes, which include a Michel Fokine evening and the full-length Jewels by George Bal- anchine — who, as Georgi Melitonovitch Balanchivadze, learned the basics of his art as a student and a dancer in the Kirov.

Still, none of the recent additions to the already vast repertoire of the Kirov Ballet has prompted the same amount of expec- tation, curiosity, interest and speculation as the `new' Kirov production of The Sleep- ing Beauty has. Based on an accurate deci- phering of the original choreographic notes (never attempted before) which Nikolai Sergeyev, a repetiteur of the Marynsky Theatre, brought to the West at the beginning of the 20th century, this `new' Sleeping Beauty is not just another staging of the popular ballet. Instead of adapting the old text to contemporary aes- thetics in order to become more legible, which is what most contemporary produc- tions usually do, the members of the reconstructing team have opted for a stag- ing that draws as much as it can upon the original production. The recreators, led by the former Kirov star Sergej Vikhariev, believe they have uncovered a timeless masterwork.

Created in 1890, the ballet was the prod- uct of a collaboration between the Fran- cophile director of the Imperial Theatres Ivan Vsevolozshky, the composer Tchaikovsky and the French-born but Rus- sian-naturalised choreographer Marius Petipa, whose long reign as director of the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg conferred a definitive stylistic imprint on what even- tually became known as Russian ballet.

Most people tend to look at The Sleeping Beauty as a spectacular, empty choreo- graphic adaptation of a silly old fairytale, but the idea for the 1890 work stemmed from specific political and cultural factors. At the time of its creation, the tsarist regime was desperately in need of any form of propaganda to boost its image. There- fore the choice of a literary pretext such as Charles Perrault's tale was anything but casual. In the story of the sleeping princess, all the principal characters are of aristo- cratic extraction, including the fairies who, being supernatural creatures, enjoy a par- ticularly high social status. In other words, it was a ballet about the court for the court. This is also demonstrated by the choreo- graphic, visual and textual — Perrault was a 17th-century court writer — references to the reign of Louis XIV that were intention- ally interspersed in the original production to establish a rather flattering and political- ly strategic parallel between the French king and the Russian tsar.

The Sleeping Beauty could thus be consid- ered the very last example of that exclusive- ly aristocratic and politically informed form of entertainment known as ballet de cour which dominated the cultural and political life of various European courts between the late 16th century and most of the 17th century.

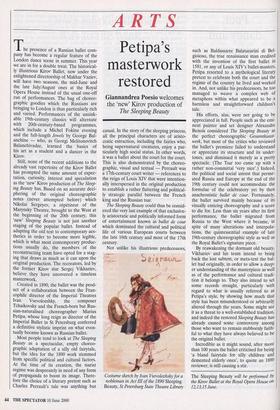

Not unlike his illustrious predecessors, Costume sketch by Ivan Vsevolozhsky for a nobleman in Act III of the 1890 Sleeping Beauty, St Petersburg State Theatre Library such as Baldassarre Balatazarini di Bel- gioioso, the true renaissance man credited with the invention of the first ballet in 1581, or any of Louis XIV's ballet-masters, Petipa resorted to a mythological literary pretext to celebrate both the court and the regime of the country he lived and worked in. And, not unlike his predecessors, he too managed to weave a complex web of metaphors within what appeared to be a harmless and straightforward children's tale.

His efforts, alas, were not going to be appreciated in full. People such as the emi- nent painter and set designer Alexandre Benois considered The Sleeping Beauty as the perfect choreographic Gesamtkunst- werk, but most of the critics who reviewed the ballet's premiere failed to understand or appreciate its structure and its under- tones, and dismissed it merely as a pretty spectacle. (The Tsar too came up with a rather non-committal 'very nice'.) Indeed, the political and social unrest that perme- ated Russia and Europe at the end of the 19th century could not accommodate the formulae of the celebratory yet by then anachronistic ballet de cour. Fortunately, the ballet survived mainly because of its visually enticing choreography and a score to die for. Less than six years after its first performance, the ballet migrated from Russia to the West where it became, in spite of many alterations and interpola- tions, the quintessential example of late 19th-century choreographic style as well as the Royal Ballet's signature piece.

By reawakening the dormant old beauty, Vikhariev and his team intend to bring back the lost subtext, or meta-text the bal- let had originally, in order to allow a deep- er understanding of the masterpiece as well as of the performance and cultural tradi- tion it belongs to. They also intend to set some records straight, particularly with regard to what is usually referred to as Petipa's style, by showing how much that style has been misunderstood or arbitrarily altered through the years. Some might see it as a threat to a well-established tradition, and indeed the restored Sleeping Beauty has already caused some controversy among those who want to remain stubbornly faith- ful to what they have always believed to be the original ballet.

Incredible as it might sound, after more than 100 years the ballet criticised for being `a bland fairytale for silly children and demented elderly ones', to quote an 1890 reviewer, is still causing a stir.

The Sleeping Beauty will be performed by the Kirov Ballet at the Royal Opera House on 12,13,15 June.

Previous page

Previous page