flebatrt anit Pruteettingit in Parliament. COLONIAL MISGOVERNMENT.

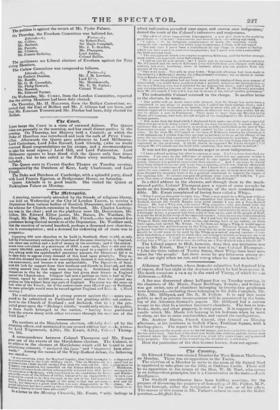

The attendance of Members in the House of Commons on Tuesday was unusually numerous. It was an "order of the day" that the House should be "called over ;" but Sir WILLIAM MOLESWORTH, the intended mover, seeing the object accomplished by the mere notice, agreed that the order should be discharged. After two Election Com- mittees had been nominated, and some routine business despatched, Sir WiLstast MOLESWORTH rose to bring forward his motion re- specting the government of the Colonies. He begun by requesting indulgence on the score of inexperience, want of weight in the House, and the great importance and extent of the subject to which he had undertaken to direct the attention of the House. He thought It necessary, at the outset, to disclaim participation in the opinion of those who thought colonies of little value or an injury to the mother country. Should Englishmen repent of having planted the North American Colonies, which had expanded into one of the greatest, mod prosperous, and happiest nations the world ever saw ? Was it to be regretted that the more Northern deserts of America were about to be reclaimed and civilized by the exertions of Englishmen ? Was it • pity that the West India markets for our products had ever existed; or was the already great and rapidly increasing trade with Australasia an evil? Should they despond over the British empire in the East, which had brought, let who would deny it, immense wealth to the country ? Sir William had himself, as Lord John Russell and Sir George Grey well knew, evinced a personal interest in the prosperity of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land; and, as Lord Howick would bear witness, had exerted himself to remedy the dreadful evils of the transportation system. Sir William proceeded to controvert the doctrine of Bentham, adopted by Sir Henry Parnell, that the mother country could derive no advantage from colonies of her own, which she might not equally secure with independent states. Fifty years ago Mr. Bentham had said " there is no necessity for governing or possessing any island in order that we may sell merchandise there"—

eta--

The doctrine presumes that we could have bad the same trade as at present with other lands, even though none of our people had gone forth to settle there; the all the countries which we have peopled and converted into glowing mar- kets the sale of our domestic produce would have been just as seeful to us, rnme„iai point of view, if they had remained independent states'—the '—the independent state of New Holland, before we had planted colonies there—the pendent state or people of America, amongst whom William Penn and his -(410'wets settled. Is not Japan, with which we have no trade, one of the right honourable baronet's independent states?' Have we such a trade, or any thieg. like such a trade, with Java as we should have bad if we had retained coon1 ial possession of that most fertile country? The doctrine of the right honourable baronet rests on the assumption that the world abouuds bade. pendent states, able and willing to purchase British goods, and that whatever may he the increase of domestic capital and production requiring ntw markets, such markets will spring up just at the moment we want them, in the form of independent states.' Has that assumption any foundation in feet or reason ? leanest help thinking that it has none—that, at all events, it is greatly to the advantase of a country like this to plant colonies, and thereby create markets where none exist, nf are likely to exist, by any other means ; and that this is preeminently the policy of such a country as England, whose power of pro- ',wing wealth by means of manufacture has no other limit than the extent or somber of the markets in which she can dispose of manufactured gtods."

Still it might be said, the sooner colonies are made independent, the better for them and for us— "The sooner the better ?—but when? Should we, for example, now at once confer independence on the last colony founded by England, with its three thousand inhabitants, giving up to that handful of people the disposal, without the slightest regard to this country, of an enormous extent of unoccupied land, ad thus enabling them, if they pleased, to put an end to the whole system of colonisation established there, and even to become a slave-holding state, as they wad be strongly, tempted to do if they did put an end to that system ? Or, should we not rather maintain that act of the Imperial Legislature which gives to the labouring classes of this country, by providing them with a continually iticressing means of emigration from low wages to high wages, prosperity, a sort of inheritance, in the extensive wastes of that colony ? Should we allow the kw who have departed to forbid the departure of the many who would fol- low, if we do not abandon our dominion over that colony ?"

The unseasonable cry of " Emancipate your Colonies," Lad arisen from the abuses of the Colonial system of government-

. Those who cry Emancipate your Colonies' appear to have seen nothing bat the abuses and evils ; they have imagined that colonies and jobbing, colo- nial trade and colonial monopoly, were synonymous terms. Instead of wishing to separate from our Colonies, or to avert the establishment of new ones, I would Oa!, distinguish between the evil and the good,.rernove the evil but preserve the good; do not 'emancipate your colonies,' but multiply them, and improve— reform your system of colonial government."

He knew bow distasteful his motion was to Members on his own

side of the House ; and, suspecting that gentlemen opposite would endeavour to represent it, in connexion with his opinions avowed there and elsewhere, of democratic tendency, he would at once dispel a portion of the prejudice by declaring, that he could not conceive a greater absur- dity than to erect democratic institutions among the millions of India, the convict settlement of New South Wales, the quarter.civilized population of South Africa, the Negroes of the West Indies, or even among the labouring rustics of South Australia, most of whom could not tell the meaning of the word "democratic " or the word " institu- tion." It might be said that he had invidiously singled out the Colo- nial Minister for attack ; but he would explain the reasons which had induced him to call for an expression of want of confidence in Lord Glenelg alone— "The Colonial Office differs materially from every other branch of the Government. All the other departments of the state administer for us who ire represented in this House ; the Colonial Office administers for the Colonies, not one of which is represented in any assembly to which that office is in any degree responsible. The other branches of Government administer only, they do not legislate : but the Colonial Office, besides having to conduct an administration comprising all the branches of government, civil, military, financial, judicial, and ecclesiastical—an administration rendered still more diffi. cult by the various institutions, languages, laws, customs, wants, and interests of a great variety of separate and widely-different communities—besides all this, which the whole administrative force of this country could hardly manage well —besides an administration more varied and difficult than that of this country, of one race, language, and law—besides this infinite variety of executive func- tions (as if the executive duties were not sufficiently complicated and incon- gruous), the Colonial Office has further to legislate more or less fur all the Colonies, and altogether for those Colonies which have no Representative Assembly, by means either of instructions to Governors, or of orders in Council, or by appointing and instructing some or all of the branches of the Colonial Legislature. Such a complication of functions in a single office would be bad enough if ;all the Colonies were close together and close to Eng- land: let us recollect, however, how widely they are dispersed, and how far from Downing Street is that of them which is nearest to England. In most of them several months, and in some of them a whole year must elapse, before a letter between the Government and one of its subjects can be answered by re. turn of post. A,petition arrives here ; who is there to press its prayer on the attention of the Colonial Minister? or who is there to take care that it shall ever be read by him ? Whether he ever looks at it must depend on the degree of his diligence and of his interest in the colony whence it comes. ()milers despatched hence should be adapted, not to the state of things which existed in the colony at the date of the Minister's last advice. therefrom, but to that which he may conjecture will exist when his orders arrive. How can he fail to err without the highest sagacity and foresight? Besides, in many cases the very subject of the letter, or petition, or remonstrance may be worn out before he eaa even know of its existence. Whatever the difficulties, then, of both legis- lating and administering for so many different communities, all these are en- lanced a thousandfold administering the great distance between the subjects and the government."

He did not speak especially of Lord Glenelg, but of any and every Colonial Minister, when he insisted upon its being the duty of Parlia- ment to take especial care that the functions of the Colonial Alinister were competently discharged-

" In every other department of the state, the Minister is responsible to this Rouse, where the representations of conflicting interests have the strongest 1110. tires to keep anxious and vigilant watch over the details of his conduct, and unnecessary delay and inactivity are exposed to constant reproach. Though the i!iiaister be not the most distinguished of statesmen, nor possess personal quali- ties of a superior description, yet his crude and imperfect notions may be im- proved in this House by the suggestions of 'his friends and the corrections of his opponents. This case seldom takes place in Colonial affairs, except when some i grave and extraordinary event, such, for instance, as a rebellion in one of the colonies, calls public attention to the subject. In ordinary cases, this House, in which the Colonies have no direct representatives, and few persons thoroughly acquainted with the particulars of Colonial affairs, can exercise no control over the details of the Colonial Office. In the Cabinet, the affairs of the other de- partments of the state are more or less within the cognizance of all the members of the Cabinet, and each Minister in his separate department may be supposed to be responsible to the whole body ; this cannot possibly be the case with regard to the Colonial IGiuister, whose department embraces all the branches of government of our numerous and widely remote dependencies, with the detail' of whose affairs it is utterly impossible for his colleagues to be acqnsinted. Sometimes, indeed, we find that the head of another department comes down to this House and snakes a speech on Colonial affairs ; but every one who un- derstauffit the subject, and listens to the discourse, can easily perceive that it is got up from a brief. In the Colonial Office, where it is so hard to do well, or even to avoid doing ill, over the details of which this House can exercise no con- trol—M which, consequently, the Minister is completely irresponsible as to de- tails—personal qualities are all in all."

He would at once admit, that he could not censure Lord Glenelg without censuring the rest of the Ministry : so much he would allow to those who charged him, in their most patriotic phraseology, of a de- sign to " let in the Tories." But were the Cabinet dissolved, the Tories could not come in as Tories-

" I do not believe, Sir, that we shall ever again have.a Government acting upon Tory principles, except under circumstances like the present, when a Government professing Liberalism adopts Tory principles in order to retain office. If the Tories were under the remponsibillty of office, they would be as liberal as the country."

Whatever might be the result of his motion in reference to the state of parties, he hadmothing to do with that. His only object was to re- lieve the Colonies from an imbecile or mischievous administration of their affairs. He wished to lay before the House the critical state of their Colonial possessions, and establish for a time at least something like responsibility in the Colonial Office. Every quarter of the globe furnished a case illustrative of the incompetency of the present Colo- nial Minister. But he must commence somewhere, and would begin with a case as to which the Member for Newark (Mr. William Glad- stone) could confirm his statement-

" During the last session of the last Parliament, the blouse instituted an in. quiry into the state of our Penal Colonies in Australasia. The Committee has been revived this session. The disclosures made before the Committee repre- sent a state of things which it was hard even for those who heard the repre- sentation to credit. Not that there could be any doubt either of the knowledge or of the veracity of the witnesses examined, but that they described a state of society, a degree of mural contamination, a condition of national infamy, so re. yoking that one was loath to believe in the exigence of such horrors. The evidence taken before the Committee of last year is in the possession of honour able gentlemen. No one, I think, who has examined that evidence, can doubt that, whatever have been the evils attending upon planting colonies with con- victs, those evils have of late years greatly augmented, and have just now at- tained a pitch which requires some prompt, vigorous, and comprehensive remedy. The first step to a remedy was ample inquiry. The House will per- haps imagine that the Colonial Minister had some part in the inquiry which has taken place ; that it was suggested by him ; that he was sufficiently ac- quainted with the great and glue ing evils in question to have proposed such an inquiry in Parliament. Not at all. On the contrary, the country is solely indebted for that inquiry to the noble lord the Member for Stroud ; from whom, before I moved for a Committee, I had the good fortune to obtain a promise chat the motion should have his support in the House. Considering the Colo- nial nature of the subject, why did I not, in order to obtain the sanction of Government, address myself to the noble lord at the head of Colouial affairs? Simply, because I believed that such an application would be in vain. I was afraid of the proverbial indecision and supineness of that Minister ; and I be- lieved that the milt. sure method of obtaining an inquiry on this Colonial sulr ject was to pass by the; Colonial Minister, and apply to another :Minister whose department is eminently not Colonial. My opinion of the Colonial Minister may have been erroneuts, but it was formed on common report and belief; and the fact therefore is, that, so far as I am concerned, the important information as to New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land now before the House, would not have been ubtained if I had not made bold, in seeking a Co. lunial inquiry, to proceed as if there were no such department as that over which Lord lileuelg presides. sir, if I had wanted any justification for such a course, I should find it in another proceeding, or rather neglect, of Lord Gle- nelg's, with regard to New south Wales. While the moral and social corrup- tion of that colony exceeds belief, its economical prosperity is equally remark- able. Nothing can be more clearly established by the evidence taken before the Trausportatiun Committee than the fact that both the evil and the good have one and the seine cause,—namely, a regular and increasing supply of con- vict labourers. if the stream of convict emigration be stayed, the source of the economical prosperity will be (hied up ; unless, indeed, some other means be adopted of supplying the colony with labourers. Amongst those most con- versant with the subject, there is but one opinion as to the evils which arise from supplying the Colonies with labour by means of transportation; but one opinion as to the necessity, if the colony is to be saved from ruin, of promoting the emigration of free labourers."

The emigration fund arising from Lord Howiek'e regulations for the sale of waste laud in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, amounted to 400,000/. ; and the future revenue from the sale of waste lands in New South Wales alone had been estimated at 200,0001. ; but what had Lord Glenelg done with this very large emigration fund?- " He allowed a portiots of it to be placed at the disposal of a private society, who expended the mash : money in sending out to the culotte shipload after shipload of the must alsantioned and irreclaimable prostitutes. Ile placed ano. ther portion of it at the dkposal of one Mr. John :1Iarshall, a sort of agent or broker for shipping, who performs (without any responsibility) for the Colo- nial Office the difficult functions of conducting emigration with the public money of the colony. But this is not all ; only a portion of this vast emigra- tion fund has been applied, however improperly, to its purpose. The re- mainder, amounting to no less a sum than 200,i1ed., is looked up in the public chest at Sydney, lying idle, of no use whatever, although the demand for labour is more urgent than at any previous time, and the colonists have vehe- mently prayed that the money which they paid for land may be expended according to the conditions on which they paid it. And this sum m the public chest is not only useless, but worse than useless; for, since ready money was paid for the land, a great part of the currency is thus absorbed and locked up in the Government chest. The loud and frequent complaints of the mile- lusts on this subject have fallen upon the ear of the noble lord as if lie were stone deaf."

Connected with New South Wales, there was another fact, which

strongly marked the incompetency of the Colonist .Minister. In 1836, the New South Wales Act expired. That act had been passed for the government of a colony the majority of whose inhabitant% were convicts. In process of time, the majority of the inhabitants were free settlers ; and they looked to the year 1836, when they expected a new system of government, with hope and anxiety. Was Lord Glenelg prepared to make the change required by the altered circum- stances of the colony ?-

" Did he submit to Parliament a new constitution for the colony? No; he only asked Parliament to renew the old act for one year—but in 1837, it will be supposed, when this act of a twelvemonth would have expired, the noble lord was prepared ?—Not a bit of it ! In 1837 he again asked for and obtained the renewal of the old act for another twelvemonth. But perhaps it may be said, that the noble lord believed that the colony was not ripe for any other than the old despotic constitution, and that he acted deliberately in renewing the old act from year to year. Not at all, Sir; for on both occ rearms the Under-Secre- tary for the Colonies, acting undoubtedly on behalf of his chief, gave notice of his intention to propose an entirely new act for the government of the colony. On both occasions, no doubt, the noble lord intended to relieve the colonists of New South Wales from their anxiety on a subject which must ever be one of the deepest interest to freemen : but on both occasions be only exhibited his own infirmity, of purpose. Is he prepared this year? or are we to renew the old act for the third time ? Are we for the third time to tell the free people of this colony, that we care so little about them as to neglect altogether a matter about which they care above all things? And if we do so, are we to wonder at their resentment? Here then, Sir, as respects one colony, are three great questions urgently pressing on the unwilling attention of the noble hird,—first, a remedy for the terrible evils of transportation ; secondly, a means of saving the colony from economical ruin ; and thirdly, a new constitution for the colony. Each of these questions is rendered more difficult by the noble lord's neglect of it hitherto."

The islands of New Zealand furnished a striking example of Lord Glenelg's carelessness- " It in evidence given before the Committee on the state of the Aborigines, that our lawless fellow subjects have excited the native tribes to wars and mas- sacres, in order to obtain tattooed heads as an article of commerce ; that they have taught the natives to employ corrosive sublimate in poisoning their ene- mies, and have actually sold them that poison for the purpose ; that these out. casts from British society have taken an active part in the cruel massacres of one tribe by another ; that they have introduced the use of ardent spirits and of fast-destroying disease ; and that, as a natural consequence, the natives are swept off in a ratio which promises in no very distant period to leave the coun- try destitute of a single aboriginal inhabitant.' Now, is this a case of urgency? is this a matter to be slept over for years, until the native race shall have disap- peared altogether? And again, I venture to ask the right honourable gentle. man the President of the Board of Trade, whether he has not received a memorial, signed by a large number of the merchants and shipowners of Lon- don trading to the South Seas, representing, that unless prompt measures be taken to establish British authority in New Zealand, is is fully to be expected that the lawless British settlers in that country will become a piratical commu- nity, like the buccaneers of old, and that even now the greatest danger is to be apprehended to our shipping? What has the noble lord, who should have been most conversant with this evil and this danger—what has he done either in be. half of the natives of New Zealand or of our shipping in the South Seas ? What has he proposed? Ilehas dune, proposed, thought of, absolutely nothing ! If it had been a matter in the moon he could nut have been more cureless about it !"

He would now turn to the condition of the Mauritius. On the au- thority of Dr. Lushington he could state, that there had been in that colony, since 1810, a perpetual violation of the law upwards of 20,000 felonies had been committed, and the slave-trade had been carried on, in opposition to the law. What has Lord Glenelg done in reference to this critical state of affairs in the Mauritius ? The answer to any in- formation the House might require, would, he feared, be "nil." Again, in Southern Africa, where the British colonies exceeded the mother country its extent, the natives were fast disappearing ; partly massacred, partly driven from their native country, where they were either forced to starve or to live by plunder. For this state of things Lord Glenelg was not particularly to blame : it was owing to the bad system on svlijdi Colonial affairs were managed. But did anybody expect a remedy from the infirm hands of Lord Glenelg ? Next, be would pass to Sierra Leone, the " White Man's Grave ;" the misgovernment of which was proverbial. The present Governor of that colony, who went there by the appointment of Mr. Spring Rice, as a reformer of abuses, bad been driven away by the jobbers and peculators who infest it and fatten on the spoils of the public. The Governor was eminently successful in conciliating the natives ; but be soon gave offence to the baud of jobbers, who style themselves the colony, and was recalled. This was the third recent case of removal in Lord Glenelg's depart- trent—

" Let me now mention a fourth, that of the new colony of South Australia; whose Governor, appointed by Lord Glenelg not more than eighteen months ago, has been just recalled. I have no doubt that this recall may be justified, just like that of Sir Francis Head; but if so, how does Lord Glenelg justify the appointment ? and, have not the appointment and the recall together, placed the colony in that state which is sometimes cellist! a state of ' hot water ? ' If we add to these four the resignation of Lord Go-ford and the recall of Sir Francis Head, there will be no fewer than six recent cases of the removal of a Colonial Chief Magietrate for extraordinary causes and under circumstances of extra- ordinary difficulty and trouble for the colony."

The West India Colonies presented a wide field of trouble, embar- rassment, and danger. Rather late in the day, Lord Glenelg had pro- mised an act to secure that which the people thought they had pur- chased with twenty millions sterling ; but there were two other mat- ters which, had Lord Glenelg possessed the faculty of attention, would Lave required its exercise—the cessation of compulsory labour, and the claim of the Negro inhabitants to elect representatives to the local Parliaments- " SO long ago as in January 1836, Lord Glenelg, or some other person writ.. ing in his name, seems to have been struck with the great importance of the former of these subjects, and even to have devised a sufficient means of prevent- ing the apprehended evil. A great danger is plainly indicated, and the means of prevention as clearly pointed out. The danger is, that the whole of the population of the West Indies should, as soon as they become entirely free, re• fuse to work for wages—should set up, each one by and fur himself, on his own piece of land, and that thus capitalists should be left without labourers, to the certain ruin of the industry of those colonies. Sir, I for one have no doubt that in all of those colonies, where laud is excessively cheap, the apprehensions of the noble lord will be fully realized. But along with the expression of his fears the Colonial Minister suggested a measure of prevention. ' It will be ne- cessary,' he says, to fix such a price upon Crown lands as will place them out of the reach of persona without capital : ' and this plan of preserving's• hour for hire, by means of rendering the acquisition of waste land more dos. cult, was strongly recommended to Parliament by the Committee to which / have referred. As the plan could be of no use whatever, unless adopted some time before the total emancipation of the apprentices, it will be supposed that the noble lord has followed up his important despatch by proposing some gun, ral and efficient measures founded on his own views and on those of the co; mittee in question. By no means : the subject remains just where his despatch left it in January 1896; as if, notwithstanding its great importance, it hat fairly slipped from the memory of the noble lord."

But from this case of culpable neglect he would pass to one of cal. pable activity— I' The planters are impressed, as was the noble lord in January 1836, wilt the necessity of taking some precautions against the year 1840, as respects the supply of labouring hands. They have devised a new kind of slavery, end, new kind of slave-trade ; and this invention the noble lord has, by an order is Council dated let March 1837, fully sanctioned. This order in Council author rises the planters of Demerara to import into that colony—to serve as iad„, tured labourers' I believe is the term employed—what class of people, does the House imagine ? Englishmen, or other Europeans, who might assert the rights as 'indentured labourers?' No. Freed Negroes from the United States, who, being of the same race, and speaking the same language as the intim colonial population of British Guiana, might be indentured labourers' without becoming slaves? No ; but a class of people the most ignorant, the most strange, the most helpless, in all respects the most fit to become slaves underthe name of indentured labourers.' They are called Hill Coolies. The country from which they are to be imported, after being kidnapped, is the East Indies, In New South \Vales, the same apprehension of a want of labourers, (which, as I have already said, the noble lord might have prevented by expending the emigration fund, instead of keeping it locked up in the public chest at Sydney,) has led to a similar project for the importation of Hill Coolies. This attempt to establish a new kind of slavery was condemned by the late Governor, sir Richard Bourke, in a despatch now before the House. Should we not mode= the noble lord for having sanctioned a similar attempt in British Guiana?"

Would this project set up Lord Glenelg as a 'statesman fit to save the West Indies from the dangers which threaten them in 1840?- " The whole of the West Indies, indeed, economically and politically, are is a most critical state. The state of the West Indies, having reference to 1840, calls especially for forethought—for precautionary measures. Are we to trust to the noble lord for such measures of forethought—of precaution ? Or are we, so surely as we place any reliance en the noble lord's energetic sagacity, to wait quietly, nothing done, nothing proposed, nothing thought of, till 1840 is upon, us? Sir, may I not say that the noble lord has neglected to take, and seem incapable of taking, any precautions to render harmless the great revolution, economical, social, and political, which must happen in the \Vest Indies nee years hence? Considering the near approach of 1840, is it fair, is it just, is it commonly humane, towards our fellow subjects in the West Indies, who, he it always remembered, have no representation in this House, to let the noble lord continue, fast asleep, at the head of Colonial affairs?"

It was not his intention to bring before the House principles of Colonial government. He had nothing to do, on this occasion, with the causes of the critical state of the Colonies ; he merely dealt with questions of fact, and the actual state of affairs. In referring, there. fore, to the North American Colonies, be should not enter into the questions between the Assembly of Lower Canada and the Colonial Office. He bad not a word to say respecting the Resolutions of last year, or the Act of this session. Against both he bad spoken and voted, and should be ready to do so again on the fitting occasion. But if both of those measures had received his support instead of his stre. nuous opposition, he should not be precluded from submitting his pre. sent motion to the House. He addressed the House on a totally different question—Lord Glenelg's manner of carrying into effect the policy of Government towards Lower Canada— "Need I recur, Sir, to those wearisome despatches which have impressed upon the country at large a conviction of the noble lord's pre6ninent unfitness for the conduct of difficult affairs? Need I, following a noble earl in the other House of Parliament, (Lord Aberdeen,) count over again the lung list of pro. mises forgotten—of assurances never fulfilled—of instructions which never arrived until it was too late—of excuses for leaving Lord Gosford without in- structions—of postponement without reason—of apologies and pretexts for delay when promptitude was most requisite—of self-contradictions, hesitations, mean- ingless changes of purpose, and other proofs of an inveterate habit of doing nothing? In fact, said the noble earl, the system which the noble lord went upon was that of doing nothing.' Doing nothing reduced to a system! This system of the noble lord has much to answer for. Who will deny that it was the main cause of the revolt and bloodshed in which it ended? if the recent accounts from Lower Canada make it appear, as I think they do, that the policy of the Government towards that country has fewer or less determined enemies there than was lately supposed, yet those favourable accounts cast still heavier blame on the noble lords extraordinary system—tending, at least, to show that the most ordinary degree of decision and promptitude would have prevented the revolt altogether. The easy .suppression of the revolt, however, by no means establishes that the colony is an so little a critical state as to be fit far the noble lord's peculiar system."

It had, however, been said that the government of Lower Canada bad been transferred from Lord Glenelg to another noble lord. So it had been said ; but he did not comprehend how that could be-

" I readily acknowledge the statesmanlike qualities of the noble earl, whose personal character seems to qualify him, above most men, for the performance of difficult and arduous public functions. Let me acknowledge the very strik- ing contrast between the system of the noble earl and the habits of the noble lord. But what then? From whom is the noble earl to receive, from whom has he already received instruction? to whom is he to make reports? who is to bring before Parliament the legislative measures the noble earl may propose? Answer to all—the noble lord, wedded to his system of doing nothing. Does it not, therefore, appear not only foolish, but almost ridiculous, to make such s person as the noble earl subordinate to the noble lord? They had far better change places; for the system of the noble lord is one in which subordinates cannot well indulge, least of all under such a chief as the noble earl ; and it is in the chief, the head of our Colonial department, that the qualities of din• gence, forethought, judgment, activity, and firmness are most required."

He had been told by Members more experienced than himself, that his motion was justified by precedent : he did not rely on that justifica- tion, but on the truth of his proposition, and the expediency of affirm- ing it. Whatever might be thought of the motion, the case, he would venture to say, was without precedent—

"Were our Colonies, ever since we established a central government for them, in so critical a state before? %ilea did so many and such grave questions press upon the attention of a Colonial Minister? Is there a single Member of the Ileum who will say upon his conscience that the present Colonial Minister ,,,,,,■

,s, any one, or is not deficient in ail, of the qualities mentioned in the . 11(,!,-,s,::::1 address to the Crown ? teir, my propositiou is true; and upon that done rely. For if such a proposition be true, who will deny the obligation )f vpea m to provide an adequate remedy for the evil? Sir, instead of searching :tier precedents, I point to the millions of our fellow subjects who are mire- „ vented in this House ;—to the great branches of domestic industry which /epee(' upon the wellbeing of our Colonial empire ;—to New South Wales, 'jilting into a state of irreclaimable depravity, with its free emigration fund belted up in the Government chest, and its oft promised constitution withheld after year '•—to the Mauritius with its 20,000 freemen, held in bondage by guiet al iosotivent and would-be rebel planters ;— to South Africa, almost denuded of its native inhabitants, distracted by factions who agree in nothing but their o res of the Colonial Office and its horde of rebels, gone forth into the wilder.

t en to conquer an inheritance of oppression over the helpless natives,—to the

■ White Man's Grave,' that job of jobs, which is rejoicing in the recall of a Reforming Governor ;—to the Nest Indies, bordering on the ruin of their in- dustry; inventing a new slave-trade with the sanction of the noble lord, in

eider to counteract the noble lord's total neglect of the means which he himself bye pointed out as necessary to preserve the use of capital in these fertile lands ; grossly evading the Emancipation Act, after pocketing its enormous price; and

hit approaching the time when, without a single precaution with a view to that strange event, 800,000 Negro slaves will, in one day, acquire the same political

sights as their masters of another race, and with the moat important of these possessions in a state little 'boa of open revolt ;—and, lastly, to the North American provinces, where open revolt has just been suppressed, where civil

bloodshed has excited the passions of hatred and revenge, where a constitution in suspended and martial law is still in force, and where there is no prospect of ram, of contented allegiance, but in the prompt settlement of a great variety of questions of surpassing complexity and difficulty. I point to all these Colo-

n ies in a state of disorganization and danger ; and then to the interests at home which depend, more or less, on the productiveness of Colonial industry—to Birmingham and Sheffield, to Leeds, Liverpool, and Glasgow, and to the

great Colonial shipping-port of London. This done, instead of searching after enuo I would remind the House of the noble lord's system, as described his immediate predecessor in office—the fated system qr. doing nothing at If truth and the public interest are to prevail, the House will surely accede to my motion, whether it is, or whether it is not according to precedent.” It might be a good constitutional principle that the whole Cabinet were responsible for the errors and defects of the Colonial Office; but be seas not aware of it- rr sot being aware of it, I have pursued the plain and simple course of attri- boring to the Colonial Minister -alone his own errors, and deficiencies. The other course—that of proposing a vote of want of confidence in the Ministry On account of the state of a single department—would have been far more ,agreeable to me in one respect, inasmuch as it would have relieved are from the suspicion—which, however. I trust that none who know me will entertain—of being actuated by personal hostility to Lord Glenelg. On that aecouut alone I should have much preferred moving for a vote as respects the Cabinet. But I feel that my first duty is to place the subject before the House in the light best calculated to obtain their attention ; and 'therefore have I co :dined to the Colonial Minister the proposal of a vote of censure for matters which are ex- clusively of a Colonial nature. I have very likely erred, through inexperience of the usages of Parliament and the constitution ; but I have acted according to the best of my judgment, and throw myself upon the indulgence of the House."

Sir William Molesworth concluded by moving-

" That tin liable address he prewitted to theil neigh expressim: the opinion or this House that, in the present critical state of many of her Majesty's ioceign possessions tu various parts of the world, it inessential to the nellbein4 or her Majest:t 'is Colonial empire, and Of the state and intim, taut domestic interests w Itieh tlyinunt Ott the Itu5r- rity of the colonies, that the Colutdal Minister should be is person in is host, oul,,e1,,,et forethoieht, joiletat-ot. mashy, and limiting% thin House and thn joildie may be able to plato reliance; out declarinc, a ith :,11 dentrenee to the constitotioual vrcrogatives of the Croup, that.,ier Majesty's pre,not Secretar. of State for the (Munn, does not enjoy the eon fide ot e of this House or of the country."

The motion was seconded by Mr. LEADER.

Lord PALMERSTON said, 'he should trzat the motion as an attack upon the whole 'Government ; fur such it really was, rhoegh apparently directed only against a single Minister. He ridiculed the idea of Sir

William NIolesworth origineting such a motion. Bad Sir Robert Peel, the leader of a great party in the House, been its author, he

should have been ready to state at length his objections.; but he would leave the House to judge whether in the present instance such a course was necessary. Lord Palmerston produced some speeches delivered by Sir William Molesworth and Mr. Leader in October lust, to show that they then viewed with alarm the diminution of the Ministerial majority, and the probability of the return of the Tories to office. If Sir William Molesworth now wished the Ministers to be dismissed, be would have acted with better judgment had he directed his motion against the Government as a body: The dismissal of Ministers would result from the success of his motion ; as no Ministry could allow one of its members to be made a scapegoat. He would not permit Lord Glenelg to be the solitary victim of this unhandsome and ungenerous attack. Lord Palmerston eulogized the public services of Lord Glenelg, especially his exertions in opening the commerce of the East. He alluded in a loose and general way to New South

Wales and New Zealand, and to the Report of the Committee on the Aborigines as proving that Lord Glenelg was not careless of the condition of those countries. At the -Mauritius, he said, content had succeeded to dissatisfaction. At the Cape of Good Hope, a stop had been put by Lord Glenelg to the encroachments of the settlers on the natives. Sir William Molesworth himself allowed that Lord Glenelg was not responsible for abuses at Sierra Leone. It was not true that the condition of the West Indies had not attracted the atten- tion of Ministers : it had in fact occupied very much of their thoughts. The events in Canada (luring the last few months had proved incon- testably the wisdom and success of Lord Glenelg's government of that colony. [This part of Lord Palmerston's speech provoked repeated sheers and laughter from the Opposition.L New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were now perfectly contented. lie therefore contended that Sir William Molesworth's case against Lord Glenelg had broken down. He then adverted to the effect of the motion if successful. Were the Tories ready to take office in conjunction with the Radi- cals? Could the Tories govern Ireland, with their " Kentish fire?"_ .

Perhaps Sir William Molesworth looked to a mixed Administration— to that which was called on the Coutiueut a government of fusion. Perhaps the honourable baronet might think that, when he had tri- umphed, he and the right honourable baronet the Member for Tamworth might meet upon the field of victory, and then divide the spoil ; or pus-

Bibly his noble friend the Member fur North Lancashire might be associated He would not move the previous question—he left that course to others; but would simply and plainly say " No" to Sir William Moles- worth's motion.

Mr. Ham. disapproved of the conduct of the present Administra. Lion, both on Colonial and other grounds ; but he was not disposed to

replace it by an Administration which he might condemn still more. He might have supported the motion if it bad been likely to bring a more Liberal Ministry into power ; but he would not vote the opposite party into power, and then vote them unworthy of the confidence of the country.

Lord SANDON had expected that the affairs of Canada would have been the basis of the present motion. He agreed with Lord Palmer- ston, that it should nut have been directed against Lord Glenelg alone, but against the entire Administration. Everybody who was acquainted with the distinguished talent and admirable private life of Lordbilenelg, would feel it impossible to support the motion. Ile could not vote

with Sir William Molesworth ; neither, however, could he be content. with is simple negative of his motion. He considered that the troubles

in Canada were mainly attributable to the misconduct of Ministers ;

and that they had not exhibited vigour or sagacity in preven. ting .a rebel- lion, which indirectly they had encouraged by the reception given to

the disturbers of peace in the colony, and by their support of those who encouraged them in this country. Under these eircionstancee, he should move an amendment in the shape of an address to the Queen, in which would be laid down his own principles and those of the party with whom he acted. He moved,