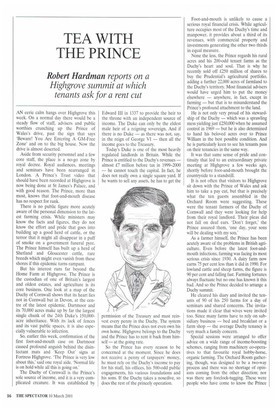

TEA WITH THE PRINCE

Robert Hardman reports on a

Highgrove summit at which tenants ask for a rent cut

AN eerie calm hangs over Highgrove this week. On a normal day there would be a steady flow of staff, advisers and public worthies crunching up the Prince of Wales's drive, past the sign that says 'Beware! You Are Entering A GM-Free Zone' and on to the big house. Now the drive is almost deserted.

Aside from security personnel and a few core staff, the place is a no-go zone by royal decree. Royal audiences, meetings and seminars have been rearranged in London. A Prince's Trust video that should have been recorded at Highgrove is now being done at St James's Palace, and with good reason. The Prince, more than most, knows that foot-and-mouth disease has no respect for rank.

There is no public figure more acutely aware of the personal dimension to the latest farming crisis. While ministers may know the facts and figures, they do not know the effort and pride that goes into building up a good herd of cattle, or the terror that it might all disappear in a puff of smoke on a government funeral pyre. The Prince himself has built up a herd of Shetland and Gloucester cattle, rare breeds which might even vanish from these shores if this epidemic turns rampant.

But his interest runs far beyond the Home Farm at Highgrove. The Prince is the custodian of one of Britain's largest and oldest estates, and agriculture is its core business. One look at a map of the Duchy of Cornwall shows that its heart lies not in Cornwall but in Devon, at the centre of the latest epidemic. Dartmoor and its 70,000 acres make up by far the largest single chunk of the 24th Duke's 150,000acre inheritance. With its lack of fences and its vast public spaces, it is also especially vulnerable to infection.

So, earlier this week, confirmation of the first foot-and-mouth case on Dartmoor caused profound anguish behind the disinfectant mats and 'Keep Out' signs at Fortress Highgrove. The Prince is very low about this,' said one royal aide. 'Normal life is on hold while all this is going on.'

The Duchy of Cornwall is the Prince's sole source of income, and it is a very complicated creature. It was established by Edward III in 1337 to provide the heir to the throne with an independent source of income. The Duke can only be the eldest male heir of a reigning sovereign. And if there is no Duke — as there was not, say, in the reign of George VI — then all the income goes to the Treasury.

Today's Duke is one of the most heavily regulated landlords in Britain. While the Prince is entitled to the Duchy's revenues — almost 17 million before tax in 1999-2000 — he cannot touch the capital. In fact, he does not really own a single square yard. If he wants to sell any assets. he has to get the

permission of the Treasury and must reinvest every penny in the Duchy. The system means that the Prince does not even own his own home. Highgrove belongs to the Duchy and the Prince has to rent it back from himself — at the going rate.

So the Prince has every reason to be concerned at the moment. Since he does not receive a penny of taxpayers' money, he must rely on the Duchy's income to pay for his staff, his offices, his 500-odd public engagements, his various foundations and his sons. If the Duchy takes a nosedive, so does the rest of the princely operation. Foot-and-mouth is unlikely to cause a serious royal financial crisis. While agriculture occupies most of the Duchy's time and manpower, it provides about a third of its revenues, with commercial property and investments generating the other two thirds in equal measure.

None the less, the Prince regards his rural acres and his 200-odd tenant farms as the Duchy's heart and soul. That is why he recently sold off £250 million of shares to buy the Prudential's agricultural portfolio, adding a further 22,000 acres of farmland to the Duchy's territory. Most financial advisers would have urged him to put the money elsewhere — anywhere, in fact, except in farming — but that is to misunderstand the Prince's profound attachment to the land.

He is not only very proud of his stewardship of the Duchy — which was a sprawling mess yielding just £250,000 when he assumed control in 1969 — but he is also determined to hand his beloved acres over to Prince William in the best possible condition. And he is particularly keen to see his tenants pass on their tenancies in the same way.

It was that same sense of pride and continuity that led to an extraordinary private meeting at Highgrove a few weeks ago, shortly before foot-and-mouth brought the countryside to a standstill.

It is not often that visitors to Highgrove sit down with the Prince of Wales and ask him to take a pay cut, but that is precisely what the ten guests assembled in the Orchard Room were suggesting. These were the tenant farmers of the Duchy of Cornwall and they were looking for help from their royal landlord. Their pleas did not fall on deaf ears. 'Don't forget,' the Prince assured them, 'one day, your sons will be dealing with my son.'

As a farmer himself, the Prince has been acutely aware of the problems in British agriculture. Even before the latest foot-andmouth infections, farming was facing its most serious crisis since 1930. A dairy farm now earns 75 per cent less than it did in 1990. For lowland cattle and sheep farms, the figure is 90 per cent and falling fast. Farming fortunes always fluctuate but no one has known it this bad. And so the Prince decided to arrange a Duchy summit.

He cleared his diary and invited the tenants of 90 of his 250 farms for a day of seminars and shared concerns. The invitations made it clear that wives were invited too. Since many farms have to rely on subsidiary business — bed and breakfast or a farm shop — the average Duchy tenancy is very much a family concern.

Special sessions were arranged to offer advice on a wide range of income-boosting schemes, ranging from machinery co-operatives to that favourite royal hobby-horse, organic farming. The Orchard Room gathering, though, was designed to be a two-way process and there was no shortage of opinions coming from the other direction; nor was there any forelock-tugging. These were people who have come to know the Prince well over the years. He has sat in their kitchens, strolled across their fields and listened to their grievances before. This week, he has been ringing them up to talk about foot-and-mouth. They were not going to conceal their thoughts at Highgrove. 'It got pretty gritty at times. There was a lot of straight talking,' recalls one royal aide. 'But the whole idea was to clear the air.'

'Nobody kept anything back. It was frank and to the point,' says John Hoskin, 54, who farms 1,100 acres of Duchy land near Dorchester. 'There was the occasional criticism, but it was constructive. And when there were gripes, they tended to be directed at the Duchy management rather than the Prince. It wasn't a case of farmers sitting around whingeing, though. People came away with some very good ideas.'

Among the complaints raised was the lack of communication between the Duchy and its tenants. Other farmers wanted more generous allowances for rebuilding work. Several pleaded for some professional assistance with the ever-increasing bureaucratic demands of Whitehall and Brussels. In each case, the Prince and his officials agreed to come up with solutions — a tenants' newsletter, a review of building allowances, advisers to help with the paperwork.

But some requests went too far. A farmer from Shropshire had no qualms about standing up and calling on the Prince to grant a 10 to 15 per cent rent reduction across the board. In days gone by, this might have been deemed downright insolence. A few centuries back, it would have warranted a flogging. Even today, some landlords would not take kindly to such talk. One or two royal aides shuffled uneasily, but the Prince took it on the chin. It was not a question he could answer himself but a senior Duchy official duly explained that every rent would be reviewed on its individual merits.

By the end of the day, there had indeed been a clearing of the air. •The Prince blushed as the gathering concluded with a vote of thanks to the host and a round of applause. 'The Prince's basic message was that financial aid is not going to get us all out of this situation, and that we all need to work together more to get out of this mess,' says John Hoskin. 'It was a very useful occasion for all concerned.'

He, like most tenants, has in fact been granted a rent reduction of well over 10 per cent. 'We had our rent reviewed recently. We met the Duchy people and showed that our profits had dropped and we reached an amicable arrangement,' Mr Hoskin explained. 'It was a solution fair to both sides — a rent reduction and an additional milk quota. We have been well looked after. The Duchy is certainly one of the better landlords.'

That is a view shared by those in a more objective position. The Duchy of Cornwall is a pretty good landlord, as is the Duke of Westminster,' says George Dunn, the chief executive of the Tenant Farmers' Association. 'You tend to find that the old-money landlords are much more understanding because they understand the need for continuity. Local-authority landlords are usually cash-strapped, and then you get the getrich-quick landlords from the pension funds and financial institutions who are interested only in the bottom line The Prince of Wales may have his own views on things such as organic farming but he doesn't impose them on his tenants. And when people are in trouble — and we are seeing real poverty now — the Duchy will listen.'

Before this outbreak of foot-and-mouth, one or two Duchy farmers had already needed some generous ducal concessions to survive, BSE, the strong pound and an ever-decreasing slice of the supermarkets' profit margin had left some on the brink of ruin. At the start of this year, most were quietly confident that, with some help from the Prince and a little luck, things could only get better. Now, some of these battered, fragile little businesses are facing extermination thanks to foot-and-mouth. Many more Duchy tenants are going to need a helping hand from their landlord.

The 24th Duke will want to do all he can to help them. Otherwise their sons may never have the chance to deal with his son at all.

Robert Hardman is a columnist and writer for the Daily Mail.

Previous page

Previous page