PETER MEDAWAR

William Cooper remembers

a great scientist and a great spirit

'KARL Popper is my guru.' One of the last things said to me by Peter Medawar, Nobel Laureate and OM so disabled by a succes- sion of strokes that he had to be brought to the dinner-table in a wheelchair; his sight reduced to tunnel-vision in one eye, the least articulation of his speech only achieved by tremendous effort. Yet aston- ishingly this came out strong and clear — 'Karl Popper is my guru,' he said, laughing. All his disabilities were momen- tarily swept out of sight by the sudden evidence of his mind, that splendid mind, being alive, penetrating and sparkling as ever. It was a moving and up-lifting mo- ment. He knew that I agreed — albeit on a somewhat lower level of comprehension! — with his assigning great importance to Popper's contribution to the methodology of science; especially in the so-called 'hypothetico-deductive' conception of the scientific process, the gist of which is that any scientific theory is always open to future criticism by experiment, and there- fore we may not say that it has been proved 'right' but only that so far it has not been proved 'wrong'. So he was making fun, as a non-religious but not anti-religious man, of gurus, of people who have gurus, and of himself: and at the same time being pro- vocative in brandishing alliance with a distinguished thinker who would not have been accepted as their guru by several philosophers of the day. 'Peter loves par- ties — he loves to laugh.' (His wife.) I was reminded of my constantly guiding quota- tion from Horace, about aspiring 'to tell the truth laughing'.

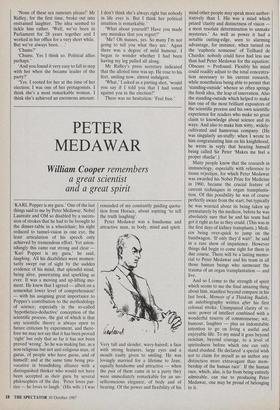

Peter Medawar was a handsome and attractive man, in body, mind and spirit.

Very tall and slender, wavy-haired; a face with strong features, large eyes and a mouth easily given to smiling. He was lovingly married for a lifetime to Jean, equally handsome and attractive — when the pair of them came in to a party they were immediately remarkable for an un- selfconscious elegance, of body and of bearing. Of the power and flexibility of his mind other people may speak more author- itatively than I. His was a mind which prized 'clarity and distinctness of vision — a most resolute determination to unmake mysteries.' As well as power it had a notable cutting-edge, seen to alarming advantage, for instance, when turned on the 'euphoric nonsense' of Teilhard de Chardin: nobody could have had less use than had Peter Medawar for the equation: Obscure = Profound. Flexibly his mind could readily adjust to the total concentra- tion necessary to his current research, while nonetheless being able to permit that 'standing-outside' whence so often springs the fresh idea, the leap of innovation. Also the standing-outside which helped to make him one of the most brilliant expositors of the scientific process and his own scientific experience for readers who make no great claim to knowledge about science and its ways. And also to make him witty, widely- cultivated and humorous company. (He was singularly un-stuffy: when I wrote to him congratulating him on his knighthood, he wrote in reply that hearing himself being called Sir Peter 'Makes me feel a proper charlie'.) Many people know that the research in immunology, especially with reference to tissue rejectipn, for which Peter Medawar was awarded his Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1960, became the crucial feature of current techniques in organ transplanta- tion. Of this possibility he was of course perfectly aware from the start; but typically he was worried about its being taken up prematurely by the medicos, before he was absolutely sure that he and his team had got it right as far as they could. (This was in the first days of kidney transplants.) Medi- cos being over-quick to jump on the bandwagon. 'If only they'd wait!', he said in a rare show of impatience. However things did begin to come right for them in due course. There will be a lasting memo- rial to Peter Medawar and his team in all those human beings who surmount the trauma of an organ transplantation — and live.

And so I come to the strength of spirit which seems to me the final amazing thing about him, manifest beyond compare in his last book, Memoir of a Thinking Radish, an autobiography written after his first colossal stroke. Unimpaired clarity of vi- sion; power of intellect combined with a wonderful reserve of commonsense; wit, humour, laughter — plus an indomitable intention to go on living a useful and enjoyable life. To my mind it goes beyond stoicism, beyond courage, to a level of spiritedness before which one can only stand abashed. He declared 'a special wish not to claim for Tnyself as an author any distinction more ektravagant than mem- bership of the human race'. If the human race, which, alas, is far from being entirely admirable, can rise to producing Peter Medawar, one may be proud of belonging to it.

Previous page

Previous page