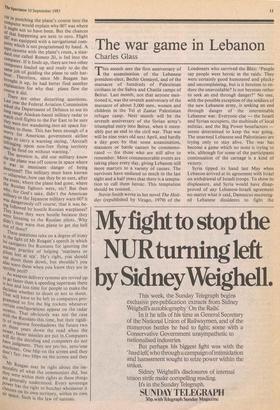

The war game in Lebanon

Charles Glass

Phis month sees the first anniversary of 1 the assassination of the Lebanese president-elect, Bechir Gemayel, and of the massacre of hundreds of Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Chatila camps of Beirut. Last month, not that anyone men- tioned it, was the seventh anniversary of the massacre of about 3,000 men, women and children in the Tel el Zaatar Palestinian refugee camp. Next month will be the seventh anniversary of the Syrian army's triumphal entry into Beirut, when it osten- sibly put an end to the civil war. That war will be nine years old next April, and hardly a day goes by that some assassination, massacre or battle cannot be commemo- rated — for those who are still alive to remember. More commemorable events are taking place every day, giving Lebanon still more martyrs to a variety of causes. The survivors have endured so much in the last eight and a half years that there is a tempta- tion to call them heroic. This temptation should be resisted.

Stevie Smith wrote in her novel The Holi- day (republished by Virago, 1979) of the

Londoners who survived the Blitz: 'People say people were heroic in the raids. They were certainly good humoured and plucky and uncomplaining, but is it heroism to en- dure the unavoidable? Is not heroism rather to seek an end through danger?' No one, with the possible exception of the soldiers of the new Lebanese army, is seeking an end through danger of the interminable Lebanese war. Everyone else — the Israeli and Syrian occupiers, the multitude of local militias, and the Big Power benefactors — seems determined to keep the war going. The unarmed Lebanese and Palestinians are trying only to stay alive. The war has become a game which no none is trying to win, although for some of the participants continuation of the carnage is a kind of victory.

Syria tipped its hand last May when Lebanon arrived at its agreement with Israel on withdrawal of Israeli troops. To show its displeasure, and Syria would have disap- proved of any Lebanese-Israeli agreement no matter what it said, Damascus encourag- ed Lebanese dissidents to fight the

Lebanese state. It did not take long for Syrian-supported Lebanese Muslim militias to start shooting at the Lebanese army.

Syria has now hurled an interdict against the government of President Amin Gem- ayel and asked the Arab League, in its cur- rent sans-Egypt form, to join it in preten- ding — as it has long done with Israel — that Lebanon does not exist and to expel Lebanon from the League. (If all the Arab states that Syria did not like were thrown out of the Arab League, there would be no Arab League.) And Syria's ruling Baath Party has revealed (so, as they say in New York, what else is new?) that Lebanon is partitioned into Syrian and Israeli zones.

Unfortunately for President Gemayel, who took office a year ago with the good will of nearly everyone in Lebanon, he has given many of his people legitimate grievances against his regime. He has not appointed Muslims to key positions, which he seems to be reserving for old friends who are both Maronite and Phalangist. He has not discussed reform of that Lebanese , system which led in 1975 to the civil war. Worst of all, hundreds of men — mostly Muslims and Palestinians, but some Chris- tians — have simply disappeared. The government — despite persistent reports that the 'disappeared' have been taken away either by the internal security forces or the Deuxieme Bureau of the army — denies all knowledge of their whereabouts. Foreign crities are calling this the 'Santiago- isation' of Beirut, with Lebanon coming more and more to resemble a US-backed banana republic.

President Gemayel is committing the classic Lebanese Christian error, which in the words of a Christian friend is, 'courting the Muslims outside Lebanon, but ignoring those wilhin. If he could win the support of the Lebanese Muslims, he wouldn't need those outside.' Gemayel had tried in vain to placate the Assad regime in Damascus, until the Syrians shelled Beirut airport, but devoted little or no attention to his own Sunni, Shi'a and Druze Muslims. They would drop their Syrian support if they believed Gemayel were serious about giving them power in a united Lebanon. His pro- blem there is, however, that whatever he gives to the Muslims, he must take away from his own power base, the Maronites. Every path has its dangers, and the fighting goes on.

Last May, when he was joining that dissi- dent coalition which the Syrians hope to use to bring down the Gemayel government, the Druze and leftist leader Walid Jumblatt spoke about the war in Lebanon. 'How long did the first civil war last?' he asked rhetorically, sitting on the terrace of the Damascus Sheraton. 'Twenty years, from 1840 to 1860. This one could take Just as long.' If Jumblatt is right, Lebanon can look forward to some relief in 1995. That first civil war, fought between Maronites and Druze in the very Chouf mountains which the Israelis have just evacuated, presents Lebanon with many unlearned lessons. It broke out when the Egyptian oc- cupying army of Ibrahim Pasha — under British pressure and after losing French support — withdrew and the Ottomans returned. The ten-year Egyptian occupation had emancipated the Christians and made them insufferable to their Druze feudal lords. For the next 20 years, there were skir- mishes, revolts and murders, culminating in the massacre of thousands of Maronites at the hands of Walid's ancestor Said Bey Jumblatt and his Druze followers. The Turks aided the Druze, just as the Syrians are helping them today. Those massacres, like the fighting in the Chouf today, might have been avoided. Colonel Charles Henry Churchill wrote in his history of the war, The Druzes and the Maronites under the Turkish Rule from 1840 to 1860 (Bernard Quaritch, London, 1862):

'Still, had the commonest consideration, or the least display of tact been evinced towards them (the Druze), there cannot be a doubt that they might easily have been won over to a cheerful compliance with an arrangement which had received the sanc- tion of the Sultan and of the European powers. Unfortunately, the charcter and proceedings of their new ruler [the Maronite Emir Bechir Kassim Shehab, whom the Turks had appointed] were such as violent- ly to inflame their animosities, and to awaken in their minds, not only a painful recollection of past indignities, but a gloomy foreboding as to their future treat- ment.'

President Gemayel and Walid Jumblatt seem determined to relive history, with Gemayel as Emir Bechir and Jumblatt as his progenitor Said Bey, and with Syria and Israel jointly playing the role of the Sublime Porte. Israel, like the Turks over a century before, supplied both sides in the Chouf fighting. Colonel Churchill wrote: 'Whole villages were burnt to the ground before their very eyes ... The Seraskier actually sent five camel-loads of ammunition to the headquarters of the Maronite forces ... The Druzcs at the same time received ample supplies of ammunition from the same quarter.' While Israel occupied the Chouf, it permitted the Maronites of the Lebanese Forces militia and the Druze of Jumblatt's Progressive Socialist Party to set up roadblocks, kidnap unsuspecting motorists and shoot at one another with impunity.

I'd heard the air was so polluted that they were extinct.' One Israeli reservist, clearly unhapPY with the role his government required him to play, said: 'These Lebanese have enough weaponry to fight for ten years. I know. We gave it to them.' Why do Israel and Syria encourage the Lebanese to fight one another? Colonel Churchill, who had lived in Lebanon over 20 years when he wrote, noted in his history: 'The Lebanon is, in fact, a point d'aPPui, a nucleus around which the various mountain tribes naturally congest. Should, therefore, its population ever be bound together by feelings of mutual trust and confidence, the danger to the supremacy of the Porte would be imminent.' The colonel's insight is as true today as it was then. If the Lebanese were even at this late date to unite, they could restore sovereignty to their country by fighting a guerrilla war, not against one another, but against their two neighbours who persist in keeping Lebanon occupied and divided. This solution is, at best, as unlikely now as it was in 1860. 'The mutual jealousy and dislike, however,' Colonel Churchill wrote, 'which animates them, has hitherto sufficed to prevent such a consummation; and the policy of the Ottoman Turks is simPlY to foment and keep up this self-consuming fire.'

Roll on, 1995.

Previous page

Previous page