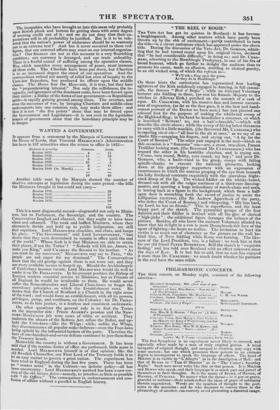

PHILHARMONIC CONCERTS.

THE third concert, on Monday night, consisted of the following selection—

ACT I.

IlisMrieal Symphony, MS. (tirst time of per- formance) Spotlit. Recitative ed Aria. Miss Bumf, Non mi dir "

(11 Dun ('iuranni) MOZART. Concert-Stick, Pianoforte, Mr. MO,CIIELES C. M. VON WEBER.

CitVZHilnI, Signor MADAM:RINI, ‘' Lime voei:"

(Zaira) MERCADANTE.

Overture. The Lirs f Finynd

ACT II.

Sinfonia, No. 8. BEETHOVEN. Aria. Miss M. B. IiAwES, " Paga CM" (II Ratto di Proserpina) WINTER. COIICeito, Violin, Herr MOLIQUE, First Violin to his Majesty the King of Wurtemburg (his first perlormance in this country) Momucr. Terzetto, Miss BIRCH, Miss M. 11. 11AWES, and Signor TAMBCRINI, " Suave eonforzo" ?-

Infra) Rosstm.

Overture, Zoira \i INTFR.

Leader, Mr. T. CooKE—Conductor, Sir G. Su Awr.

The first Symphony is an experiment never likely to succeed, and especially when made by a man of truly original genius. A mind incapable of original thought, and unequal to creation, may copy with some success ; but one which possesses these powers in an eminent degree is incompetent to speak the language of others. The hand of 11Iwros is as visible in "L'Allegro" as in the description of Hell ; and that of Beim in "Tam 0' Shanter" as in "The Cotter's Saturday Night." Such men never write like this or that person. It is MILTON and BURNS who speak, and their language is as much part and parcel of themselves as their thoughts. So is the music of SPOHR, of HAYDN, Of HANDEL, of PURCELL. No matter what the theme—he it gay or grave, graceful or sublime—their minds reflect the ideas of grace or sublimity therein engendered. Words are the symbols of thought to the poet, notes to the musician ; and he who attempts to convey these in the phraseology of another, can scarcely avoid presenting a distorted image.

MENDEL:SOHN BARTHOLDT.

SPowR's Symphony is intended to depict the style of instrumental com- position one hundred years since, fifty years since, and the noisy style of the present day. The first movement, in its outline, is thoroughly

Handelian ; but the colouring is that of the composer. The subjects, though not borrowed, are precisely such as HANDEL might have written ; but their treatment frequently betrays the hand of SPOHR. The melo- dious character of MOZART pervades the andante, with frequent indica- tions also that it was the product of another mind. The last movement is evidently a satire on the noisy shoolt and, as might be anticipated, is the weakest portion of the Symphony. This is a level to which SPOIIR has not the power to descend. Having said thus much of the Symphony

as a composition, it is necessary to add that it was grievously damaged in performance. The time of the last movement, which ought not to have abated a jot of Aumsa's usual rapidity, was ambled through at a

regular jog-trot four-in-the-bar pace. It was a joke delivered with measured utterance and a sedate countenance, therefore no joke at all. Had COOKE, instead of being the (so-called) leader, occupied the post of conductor, we should have at least understood what the composer meant.

• The other prominent novelty of the concert was the appearance of MOLIQUE, one of the most celebrated performers on the violin of the

German school. Of this school it has been justly remarked, that "al- though proceeding, like that of other countries, from Italy, and con- tracting no inconsiderable obligations to it in its progress, it is yet less indebted to the Italians for resources and support than the school of

France in England." The German violin school, and especially SPOHR as its head, aims at something more than mere exhibition of difficulties.

A concerto includes these, but it includes something more. It aims, in the first place, at excellence as a composition—at the production of it work to which the musician can listen with entire satisfaction ; and is pot content so to designate a series of commonplace noisy passages, fit only to serve as the prelude to a pantomime, interspersed with a succes- sion of what are termed "brilliant passages." Hence the German player is not a mere fiddler—lie is also a musician : master of his

instrument, he is master also of his art. The Quartets of Havnts, MOZART, BEETHOVEN and &MOB, are the models upon which his

style is formed ; which thus assumes a degree of elevation which the disciples of the French school rarely attain or even seek. These characteristics were embodied in Herr Momorres composition and performance. The former was complete as a work of genius and art ; the latter finished with the highest polish, and exhibiting not only a brilliant finger but a cultivated mind.

MENDELSSOHN'S fine Overture suffered in a like manner, from the same cause, as the Sinfonia of SPOIIR. The sluggishness of the band was apparent throughout the evening—it scarcely resembled the machine which, at the previous concert, under the constraint of Mo- SCHELES. moved with such vigour and precision. Miss BIRCH went through her song with her habitual sweetness of tone, and absence of articulation and expression. TAMBURINI'S return to the Philharmonic orchestra was greeted with vigorous applause; and we congratulate the supporters of this and other concerts, that so accomplished a singer is freed from the grasp of LA.. PORTE, and at liberty to exercise his splendid talents whenever they may be in request. His song was unforttuntely chosen—a bad specimen of a bad school. This, we know; is not the singer's fault ; for TAMBURINI is able and never unwilling to sing the classical music of his own country. Let us sum up our notice of this concert with thanks to MOSCHELES for his masterly performance of WEBER'S Concert-StUck.

Previous page

Previous page