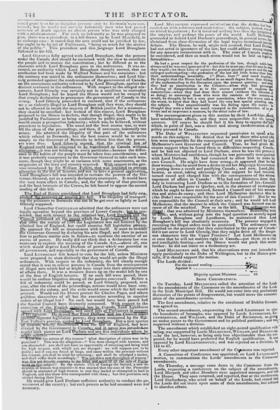

In the House of Lords, on Tuesday, Lord BROUGHAM moved

for a copy of the date of Sir Charles Paget's attendance on the Special Council of Canada. On this motion, Lord Brougham proceeded to speak at length respecting the ordinance of the Special Council, and

Lord Durham's proclamation for the banishment of Nelson, Papineau, and the other leaders in the Canadian rebellion. He declared that the th:mg else. But there was an express exception, in the teeth which these ordinances went from the beginning to the end. The Goveruor anucit were tiedluifrom repgalin. ctet_ki,g any act of Parhamen.L.LNoe7There was the 7th William I1 ylne—,1ates[ to ihe tiler 077111 treason. surely thaCivadian Act di'Mt give the power_of_reiealing this law in dividtilliffsTa-fiZe;IsF.-passuirienMEF on 09c w treason, without a challenge of jurors—without a y of the indictment— without five days' notice to witnesses—witTaiut, uurliht, alrEguards so carefully given to the subject by that important statute. Let it he observed that Mr. Papineau and fourteen others were sentenaritilike manner, though they never could be tried, their only ostensible offence being that they were out of the country.

He hoped the Lords would mark the marvellously incredible absur- dity be was about to point out— The Governor and Council did not begin by declaring what they meant,— namely, to pass a hill of attainder, and say that A, B, C, being guilty of high

treason, should suffer penalties ; ;rut, without declaring that they were guilty, these men were sentenced to be banished to the island of Bermuda; and if they came away from that place and returned to Canada, thew, in that case alone, were they to be treated as being guilty ot high treason. So here was a kind of high treason in suspense—a sort of springing treasonable use—by which these men were to be punished, not kr any act they connuitted in Canada, but for havin left Bermuda. Now that ordi n

which most sa u an y smite treasonable olfencea to a very small number imieed, Well, this monstrous absurdity in legislation was followed up by a de- claration that twelve or fourteen persons were guilty of the murder of Lieu- tenant Weir, and " that nothing in any proclamation of her Majesty should extend, or be held or construed to extend, to the cases of these men." So that if the Queen should think fit—as she had a perfect right to do, unless the Vice. roy over Canada were viceroy over the Queen also—to pardon all these men, this proclamation shut her out from pursuing that course, which, for aught he knew, might be the most wise and salutary that could be adopted. It was clear that what was meant by the words, " that nothing in any proclamation should extend to the case of those who murdered Lieutenant Weir, was this— that nothing in the proclamation then issued should be so interpreted. But his complaint was, that it was worded in a loose and equivocal manner.All things were dune under the colour of the Coercion Act, though he had that the Governor and Council were expressly forbidden to infringe upon the statutes of England.

But when and how was the authority of the Governor of Canada extended to the West Indies? The banished men were to be subject to strict surveillance—

Now, in God's name, let not Sir Charles Paget attempt to institute any such system of surveillance; for if he did, he would be liable to an action for false imprisonment. The gallant Admiral had no power whatever to touch a hair of these men's heads as long as they were in Bermuda, by an act agreed to in Canada. The ordinance passed in Canada declared that if these men were found at large, they should be punished by death: so that it mattered not whe- ther they left Bermuda or were found in Loudon, this Governor and Council of Canada had, it seemed, an equal power to visit them with punishment.

Lord GLENELG admitted that the jurisdiction of the Governor- General of Canada did not extend to Bermuda ; but the main question was, whether Lord Durham had consulted the real and substantial in- terests of the province— The justificaton of his conduct was to be found in the great principles CD which be had

lming the a a proceeded to legislate. It was for the objrct of pacitication—of I rin the eigita•ion, and mutual animosity which existed in the ca

worinee that he had emend on his mission ; and if he had misted an ordi. atom migILL-he...ita..maccuractbs- ; tin 1 He knew that in the country most affected, aeling was decidedly in favour of the course Lord Durham had t e geared e- Lord Durham was called upon to consider the situation of prisoners w—hoilw.ere charged with and supposed to be guilty. of high crimes. It was a difficult task to determine whether he should exercise the severity of extreme w act in a lenient spirit towards them. He thought it his duty to act tab n or much lenity as possible ; and, with respect to those who had pleaded oilie the merciful course which he took gave universal satisfaction in that ;,-0,f`e'ce and the adjoining one, to all the parties concerned. It was capable of wad from the accounts which were received, that whilst both parties previous to ;a decision were calling for extreme measures, one side for violent punishments, iad the other for a complete amnesty,—when Lord Durham announced his de- wanination, a general feeling of gratification prevailed throughout the pro. vial. As to thole parties who had pleaded guilty, he did not think the pro- priety of the ordinance in their case could be fairly questioned. And with iespeet to the other parties who had absconded, and against whom warrants of Immo had issued, surely, whatever might be the palliation of their conduct, (if any such could be found,) the step taken by Lord Durham was one de- manded by prudence and precaution. He firmly believed that the course taken by Lord Durham was calculated to promote peace and tranquillity.

As to the legality of the ordinances, he would give no opinion.

Lord BROUGHAM remarked, that Lord Durham might have said, with perfect propriety, to the banished persons—" I will allow you to go away, on condition that you shall receive punishment if you re- turn "— But it was not only ill -al, but nonsensical, to make their punishment for treason depend, not on the acts which they had perpetrated in Canada, but on their quittiug Bermuda. His objection was not to the lenity shown to the pri- soners, but to the powers exercised by the Governor and Council in a manner which the law did not entitle them to do. If there were any one of the fifteen Judgqwho were accustomed to consider criminal acts, ana who dISTME pronounce, the ordinance Which abrogatedihe statutes of En lane be site at, he s‘ould at his error. Hr"raTconsu ci some o t e es awycrs in 14nm-tinter Ifal on the subjict, and they had not a shadow of doubt on the point. Lord MELBOURNE implored the House not to be led away by Lord Brougham. The worst consequences might ensue from encouraging these attacks on the Governor of Canada— "It is, unfintunately, one of the evils which appertain to popular govern- ments (for all governments have their faults)—indeed it was one of the ingenita riiia of such a form, that in consequence of political strife, of political attacks, and party and personal dislike, the enemy of the country, whether foreign or domestic, has always found the greatest assistance and encouragement in the bosom of the legislative assemblies. That has always been the case, and it is undoubtedly a great misfortune. I shall say. nothing of the law of the case. The noble and learned lord is always twitting and reproaching me with my ignorance of the law, which he maintains I ought to know better. I shall therefore say nothing on that subject on the present occasion ; and it would be perfectly useless that I should do so, because my opinion can carry with it no weight or authority. But I beg leave to assure your Lordships, that, with the exception of that part which relates to the island of Bermuda, and which is erroneous, became it is clear that Lord Durham could not advert to places beyond his jurisdiction, all the other parts, I can take upon myself to say from aufhoritietZhieLloaaalluakts.aml ia_whiell.LeaDrefx co le al, and warranted by the powers committed to Lord Durham."

Lord ELLENBOROUGH contended, that it was the duty of Parliament to pay especial attention to the manner in which Lord Durham exer- cised his unusual powers.

Lord BROUGHAM replied to Lord Melbourne's observations respect- ing the evils arising from public discussion of the acts of Government and its functionaries— "Popular government, it was said, like all others had its evils. Who denies it? But 1 was not prepared to expect that that should be set down among the miechiefs which I reckon the greatest beauty, the highest benefit, the most ample advantage, the consummate glory of a popular constitution—namely, that it abhors arbitrary power, that It courts publicity and investigation, that it challenges inquiry, that it defies opposition, that it stands upon its own merits, and above all, that it never seeks to skulk in the recesses of irresponsible power, and to escape from scrutiny ; and, more, that it never overrules the principles of justice and of known law, by planting in its place a wretched substitute, consisting of a law vague and unknown: and, if any thing could be more op- posite to the principles of a free constitution, it is to imagine that expediency should be pleaded as an extenuation for what cannot be defended—namely, ille- gal acts and illegal laws. Am I tube told and taunted that party feeling is at the bottom of this inquiry, that factious strife is the cause? As it has been insinuated of these observations, that personal feelings are the cause of them, am Ito be told, that at the end of the session durin: the •a

tupon eve

bet name an tar havm eta t as_weithLyes

ezercis at wou scrutin oc ion sister t

ssin Mr' take care that its nazter.a.abauld of which 'oat —Am o e to —and in eed I am much surprised at being told—that personal feelings have any share in these observations? But I am surprised a good deal more, for this just and plain reason, that when Lord Dur- ham was unfairly attacked for the last part of hie conduct that has come before the House, namely, the appointment of Mr. Turton, and when no one member of the Government, who are now so sensitive upon the subject, and who now say that any scrutiny upon his conduct is unfair, rose to defend him, I was the only person in this House who ventured to say a word either in defence or extenua- tion of his Excellency. I think, therefore, that in these circumstances, I may defy the charge that has been levelled against me, of allowing party feeling or personal influence to guide my conduct on this important question. I deem this question of the highest importance, of the last importance to the peace of the colony, to the credit of the law, and to the credit of the Government itself, and to the credit of this House, which passed the coercive bill."

The Duke of WELLINGTON, though disapproving of the nightly

attacks on Lord Durham, really thought that steps should be taken to teLthe_goyernmept of Canada right on proceedings_ which appeared to belatalktillegal,_ Lord Durham disinot appear to know what he was about .."Infrffiscussion ended with a notice from Lord Baounliabt that he should make the conduct of Lord Durham, in respect to the ordinance and proclamation, the subject of a formal motion. On Wednesday, Lord Baouctiast introduced a bill " for declaring the true intentiThd meaning of anc pA t amused ii. the present session of Mittlit'd'IrtrAet"-to-ttraire-temitrraryprovision for the government of Lower Canada;' ifird-nrindemilfyitirttrule wInfiras issued or acted undela certain ordinance made under coLour of the said Act." This bill was read a first time without remark.

Lord BROUGHAM moved the second reading on Thursday. He said that his original objections to the Canada Coercion Act were not in the least degree mitigated, on the contrary they were strengthened ; but having given his decided opposition to the enactment of that mea- sure, he thought he should best perform his duty as a citizen and a legislator by endeavouring to carry the law into successful operation. The object of the Canada Coercion Act having been to provide for the government of the province of Lower Canada during the suspension of its constitution,—with the view, how- ever, to the restoration of that constitution at as early a period as the state of the province would allow,—it was manifestly the duty of the persons to whom the execution of the act was intrusted, to use the great powers it conferred as sparingly as possible, so that the feelings of the people might be conciliated towards what must appear to them a most arbitrary proceeding, and their good. will to the mother country regained. It was of the highest importance that the unconstitutional authority established by the Act should be ex- ercised in as constitutional a spirit as possible. But what had the Governor-General and his Special Council done ?—

If he (Lord Brougham) had said to their Lordships at the time this Cana-1 dian Bill was passing, " Do you mean to suspend the constitution, and to aria ' a dictator with the power of confiscating any individual's property, of seizing his person, of condemning him unheard, of passing bills of pains and penalties of his own mere motion, and, with the assistance of his Council, of proniulging against whom he chose, and tor what he pleased, at any moment, acts of at- ' tainder ? "—if he had said, " Do you mean in this bill, not only...to make the Governor of Canada the supreme Lulgiver, witbliis touncil, but a Ink° civil tri7 'criminal in every one inanaa ease, as to ins property, hislinib, his libertyL and his ote, a aupreme criminal Judge without a )peal; dna-rnar-tre, one same "'Peon, witFiEe assistance or VT Ceftncit, snout ecute the criminal law as well as the civil in all cases which the prerogative of the Crown, his master or mistress, whom be represents, balways alliimea delegated to theiwroaa iudies."—should he not have been told at once, and by every man who had supported the bill on the policy in which it had originated, whether sitting on that or on the other side of the House, that he was putting an extravagant gloss upon the bill, that he was arguing upon the letter against the spirit, and that no man living would ever have dreamt of conferring such powers? But to make it snore clear, elsewhere, in the other House of Parliament, that no such unlimited power bad been given, a great lawyer, the worthy successor of the Romillies, the Pigots, the Erokines, the Gibbsers, and the Ellenboroughs of past times, he meant the late Solicitor-General, his honourable and learned friend Sir William Follett, not being satisfied with what hail satisfied them, in- serted words to which their Lordships' attention bad more than once been called by him—a proviso expiessly declaring that no law or ordinapce of the Gnvprnar in Council Mould-be passeorwhich should reral or suspend or alter_ any Aar p.f, iTria me ut.

was ailegeorthat Wolfred Nelson and the other persons confined at Montreal had pleaded guilty : but their friends in America and in this country stated, that when a paper containing a confession of guilt was handed to them for signature, they refused to sign it. They were willing to go to Bermuda, because, since the expiration in 1834 of Sir Robert Peel's ,lury.law, the old law was revived, and the Sheriff, an officer removable at the pleasure of the Government, selected the juries; and because they were aware, as was now admitted, that Lord Durham's jurisdiction did not extend to Bermuda, arid that as soon as they were three miles from the shore, if the Captain prevented them from going on board any other vessel, or wheresoever they might wish to go, they might bring an action against him for false imprisonment. If they had really been disposed to plead guilty, as ININ alleged, they would have been taken into a court of justice, where their plea would have been regularly recorded ; and then the Government might have commuted the sentence of the law. Lord Durham (in a despatch,

partly laid with the Ordinance and Proclamation on the table) said he would not send the prisoners to a " penal " colony : but Bermuda was a penal colony—there was forced labour there. That, however, was

immaterial to the argument. Supposing that Nelson and the Montreal

prisoners had confessed, still who could justify the condemnation of Papineau and the absconding offenders ?—

What would Lie said of that part of the ordinance which condemned all those men who were nut in the province ?—who had not only never been tried, but with whom no communication had taken place, who did not know that the ordinance existed, who had no notice of the intention in order that they might oppose it—these men who had never confessed, but who positively denied, many of them, all participation in last winter's revolt—men who did not con- fess, even, like Nelean, that they admitted the fact but denied the inference, but men who denied both the fact and the inference,—what would be said of a proposition no monstrous, that the fact, and the only fact, necessary to pass an act of attainder was the setting foot across the Canadian frontier, although the party was married, unprosecuted, unheard, ignorant of the act, and without notice of the act—ay, and without a day being assigned on which they might appear and stand their trial even according to the bad jury-law of Canada. But all this hall been done. This was the case before their Lordships. In the highest court of judicature in the world—in the highest court of British justice, where the hair of a man's bead could not be touched without full hear- ing, open investigation, and fair trial—he need not ask whether such proceed- ings ought to be condemned.

But it was argued, that Lord Durham and his Council being on the spot, were the best judges of what ought to be done : that might be, yet it gave them no power to pass h;lls of attainder against absent men. Lord Brougham quoted several precedents to show, that even in the worst times, notice had been given, and opportunity allowed to accused persons to appear and defend themselves, before they were subkcted to attainder. In minor points the ordinances were illegal. There were two gross misnomers. Edmund Bailey O'Callaghan was called Edmund Burke O'Callaghan ; Jeremy Bentham Ryan was called John Ryan. These men could not have been convicted an a court of justice, on account of these misnomers. Again, Louis Perrzult did not ab- scond after the outbreak ; be was in the United States, on business, before it commenced, and remained there, beeausc his brother had been accidentally killed in a scuffle not connected with the outbreak there-

fore this man did not "abscond." Against Mr. Wright there was a warrant of sedition, (an offence punishable only by fine and imprison- ment,) not of high treason ; yet he too was condemned to death.

Now. would the Peers of England have passed the Canada Act, if tbey,jould Jiave suRposed that such things would have been done under it? t was manifest that a bill of indemnity was required ; and he vould grant it so far as theKoine persons sent to liermuda'wcre con- cerned ; but he word I not entirely indemnify men who had pmsed sentence of death against an absent person who was only charged with a inisdeinessiour. For such an indemnity as he was prepared to give, there was a precedent, in a bill drawn up by Lord Mansfield, in an embargo case : it stated that the acts could not be justified by law, but ought to be by act of Parliament, "being so much for the service of the public." This precedent and this language Lord Brougham followed in his bill.

Lord GLENELG fully agreed with Lord Brougham, that the powers ender the Canada Act should be exercised with the view to conciliate the people and to restore the constitution ; but be differed as to the character which Lord Brougham gave to the ordinances. It was as- sumed, on authority which Lord Brougham thought correct, that no confession had been made by Wolfred Nelson and his associates : but the contrary was stated in the ordinances themselves ; and Lord Gle- tielg protested against the condemnation of the government of Canada, on the anonymous authority referred to by Lord Brougham, against the distinct averment in the ordinances. With respect to the alleged mis- nomers, Lord Glenelg was certainly not in a condition to contradict Lord Brougham; but he hoped the House would not be swayed by that simple declaration to pronounce the government of Canada in the wrong. Lord Glenelg proceeded to contend, that if the ordinances tre..-e so violently illegal as Lord Brougham said they were, they should not be allowed to insult the majesty of British justice for a moment— they should be annulled : but instead of this course, Lord Brougham proposed to the House to declare, that though illegal, they ought to be justified by Parliament as being conducive to public good. The bill would create a prospective indemnity; which was, he believed, without precedent in legislation. The usual and the best course was, to wait till the close of the proceedings, and then, if necessary, indemnify the actors. He admitted the illegality of that part of the ordinances which related to Bermuda; but the best course would be to write simply to the Governor of Bermuda to inform him that the prison. ers were free. Lord_Glenelg argued. that Ike criminal law of England coultsiot:Wstruposes1 to be transferreiLto. Canada wit alteration—it was not binding in every particular—because the differ- en—c—i=e habits of the people must be taken into consideration ; and it was perfectly competent to the Governor-General to take such mea- sures, though they time be at variance with some enactments, as the exigencies of the tame and country required. With respect to the_gyo. "also introduced by Sir William Follett, that was intended toyrev,ent alteration in the law ot tenures, and not to have a general application ViiirBrotighim's bill was intended to restrain the powers of the Go-- vernor-General, not as a mere!! declaratory enactment. It would have the very worst effect in Cana a; and, for the safety of that province, and the best interests of the Crown, he felt bound to oppose the second reading of this bill.

The Earl of RIPON considered that Lord Brou ham had fully este- Pliskj_tki 1 calgagtru,LEmi; -i,s VI . e 1 ega ity arininspoit- ing the prisoners to Bermuda vi-Tr.srVit-ToThe got over so lightly as Lord Glenelg supposed.

Lord Chancellor COTTENII AM admitted that the ordinances were not legally operative beyond the province of Lower Canada: k u t heson- tended, that with respect to the criminal la w Lord Durham and the —COUlicITIOITCslid—all—iN power wirefi the:Ugialaturei ad telkana that since lie statute of 1791 are f-Legislature was not et-fired by the irTininal law of England, but could exercise full legislative rswers. Re opposed the bill as inconsistent with itself. It went to rearm ffe Governor-General by declaring his acts illegal, and then to permit him to perform similar acts in future—to continue the exercise of an excess of power. He really did not think that a declaratory law was necessary to explain the meaning of the Canada Act,—above all, one which would deprive Lord Durham of power which was essential to all government, and especially to the government of Canada.

Lord LYNDHURST felt bound to vote for the bill, unless Ministers were prepared to state distinctly that they would set aside the illegal ordinances. With respect to the indemnity, the bill clearly enough stated that it was to relieve persons in Canada from the consequences of illegal acts which had or might have crept into their administration of affairs there. It was a measure drawn up on the model left by one of the first of English lawyers. If no such bill were passed, there would be endless litigation among all the parties concerned. Before a bill of indemnity could be passed, as Lord Glenelg proposed, next year, after the close of the proceedings, actions would have been com- menced in the colony, and the evils would ensue which the bill would ptevent. Would not the House protect Sir Charles Paget, and others guiltless themselves of all but the execution according to superior orders of an illegal law ? No such law would have been passed had the Special Council been discreetly composed. With respect to the extension of the En lish Aiizinal law tn Canadii, Lord L. visdburst

reaVal fo d Brou m and cued acts rPriilarnent in suport o is o imon. e erne

e.ae re se supreme YsUZ—ttlYe Over i thevwert.restrained by Sir W- (4 riniTollett's proviso, It e ke,Lord Broirn., But a new speciss ot ticasok mlfisltrIllTon eiTE witaitue Iiiiii-Tif Efigland, had been C-feated by the Government in Carissgssusod it never wasintendesteto cot:fa-Web ismer on-Liiii-D-u-rham and any five individuals whom he 'fiiit s ere-LT— ••••••••••■•■•••■ V4 WU was the nature of this treason? what description of crime was to be punished ? This was the allegation—" You were charged with treason, and you absconded: you shall not have an opportunity of returning and being tried for high treason, with which you are charged : we will suppose you to be guilty; and if you are found at large, and come withiu the province without our consent, you shall be tried for returning ; and shall be adjudged a traitor, and shall suffer death accordingly." Was not this a new description of treason ?

unt-this.untsdirsellic all e_ac_a_o _aria- sepnt,owles subject?-rtylte statute 17th of George t1T-Second, a new de. cription of treason was enacted—it was enacted that the sons of the Pretender should be attaiuted of high treason in case they landed or attempted to laud in England, and also those who corresponded with them ; but this provision only existed during their lives.

He would give Lord Durham sufficient authority to conduct the go- vernment of the country ; but such powers as he had assumed were not necessary. .

Lord MEL DOUR NE expressed satisfnct:on that the delihre bad bee cm ried on with calmness mid moderation the subject, itideed, leas ,nh DO trivial importance ; for it involved nothing less than the integrity;i the empire, and perhaps the peace of the world. Lem% Melbourne proceeded to defend Lord Dui ham's proceedings, in general terms; i. abstained from close discussion of tbe legal topics introduced into th, debate. The House, he said, might rest assured, that Lord Delhat1 had not acted in ignorance of the law, but could adduce strong rea,,t for any measure inconsistent with it. The state of Canada ough; be considered, and then so much stress would not be laid on legaii, formalities— He had a great respect for the profession of the law, though name hordi always said he was very Ignorant of it : but this he must say, that let men be ‘,4, they would—let them have of nature the greatest possible powers and tile mott enlarged understanding—the profession of the law did little better than feta: their understandings invariably. (" Hear, hear 1" and much He thought that the House had suffered in no small degree from that fettera,' of the understanding in the discussion upon the present question : and the; they had an insurrection in the Colonies—when they had epee:Irani a feeling of disapprobation as to the course pursued to suppress lig insurrection—when they had done their utmost (without the intention so doing) to encourage those who were the enemies of the country...would, he thought, be but a very poor consolation, when the worst cam, t,, the worst, to know that they had heard the very best special pleading sp' the subject. That unquestionably was his feeling upon the matter: hi thought they were a little too much cramped in the consideration of $0 treme and so important a measure, by the strict rules of law.

The encouragement given to this motion by their Lordships Aoat; have mischievous effects, and they were responsible for its cono4 quences. Of course he should feel it his duty to oppose thebillf. which, in point of fact, was a direct and strong condemnation of the policy pursued in Canada.

The Duke of WELLINGTON requested permission to speat a few words on this subject. He denied that he and those who acted wtth him were responsible for the consequences of acts performed by Lord Melbourne's own Governor and Council. True, he had given Mi. nisters support when he found them in difficulties respecting Canada; and he had not objected to Lord Durham, since he was the person in whom Ministers had confidence, though he was personally unacquainted with Lord Durham. He had consented to allow him to name hii own Council. He might have done wrong—it appeared that he bad done wrong—but he acted from a desire to aid her Al ajesty:s Government in putting down a revolt and pacifying Canada ; and now, LorchMel. bourne, as usual, taking advantage of the support he had received, turned round and charged him with the consequences of the minus nagement of affairs in Canada! Why had not Ministers done thei; duty in instructing Lord Durham as to the formation of his. Councill Lord Durham had gone to Quebec, and, in the absence of instruction which he ought to have received, formed a Council out of his secrets. ries and aides.de-camp ; and then Lord Melbourne declares that he (the Duke) was responsible for the acts of this Council ! But he was not responsible for the Council or their acts ; and be would tell Lord Melbourne that the manner in which the Council was formed was the cause of all the mischief. Now as to the bill. Tlirces were .ille 1:_ that was admitted by Ministers themselves. -1&ri—Whisig must e one; and, without going into the legal question so acutely argued by Lords Brougham and Lyndhurst, he maintained that Lost Brougham's bill was absolutely necessary. The persons engaged in executing the illegal orders must be protected. The ordinances were justified on the pretence that they contributed to the peace of Canada: did it not occur to Lord Glenelg, that they might drive all the danger- ous characters into the Upper Province ? Let Lord Melbourne say at once that he will set matters right in Canada—put them on a cleat and intelligible footing—and the House would not push this matter further : he did not insist on a declaratory act.

Lord MELBOURNE said, that his observations were not intended to apply particularly to the Duke of Wellington, but to the House gene- rally, if it should support the motion.

• • The Lords divided : 41*

For the second reading

Against it 136 • Majority against Miuisters 18

IRISII CORTORATION S.

On Tuesday, Lord MELBOURNE called the attention of the Lords to the amendments of the Commons on the amendments of the Lords in the Irish Municipal Bill. He would not enter into any preliminuy discussion of the points of disagreement, but would move the consider. ation of the amendments seriatim.

The first amendment, relative to the enrolment of Dublin freemen, was agreed to.

The second amendment, empowering the Lord-Lieutenant to alter the boundaries of boroughs, was opposed by Lords LYNDHURST, LENBOROUGH, and WICKLOW, and the Duke of RICHMOND, as givrog an undue power to the Government and its political partisans ; and wail:. negatived without a division. The amendment which established an eight-pound qualification with rating, was supported by Lords MELBOURNE, WICKLOW, and Sam:mishit —by the last, however, as being only less objectionable than the ten- pound, for he would have preferred the English qualification. It was opposed by Lord ELLENBOROUGH ; and was rejected on a division, by 144 to 67.

Every other important amendment of the Co/mons was rejected.

A Committee of Conference was appointed, on Lord LYNDHURST'S motion, to communicate the Lords' amendments to the Commons' amendments.

On Thursday, a message came down to the Commons from tile Lords, requesting a conference on the subject of the amendments. Lord Morpeth and other Members were appointed managers, and left the House. They soon returned, and reported, that at the conference, Lord Shaftesbury, who acted on behalf of the Lords, bad stated tbat the Lords did not insist upon some of their amendments, but refused to abandon others. Letd Joue RUSSELL moved that the amendments, with the Lords' be read by the Clerk ; which having been done, he practeded

goons, address the House. It appeared that the Lords partially agreed to & amendment of the Commons respecting charitable trustees as they only insisted upon continuing the present trustees to October 1840. They had not insisted upon some other amendments ; but the clause ting the franchise was restored to the state in which it first came respec down from the Lords ; and, feeling that this clause was of so great iamortance, and that there was no hope of inducing the Lords to re- ceje,—not being himself disposed to go any further in the way of con- cession, having already made great and important concessions, be would not carry on the controversy any longer, but would propose to postpone the further consideration of the measure to the next session. He was lad however, that some obstacles had been removed, and hoped that next session the two Houses would be able to agree upon a measure. The differences in the way of successful legislation were not so wide as they bad been formerly. The form of getting rid of the bill at present, which Lord John proposed, was that the I'Ards' amendments be considered "this day three months." Mr. SHAW disapproved of the summary manner in which it was proposed to get rid of this measure ; but would not divide the House against Ministers. (There were only four Opposition Members pre- sent when Mr Shaw sat down.) Mr. SPRING RICE said, that in framing a Corporation Bill, the ob- ject was to give contentment in Ireland ; and therefore Ministers could not support a measure which would have a contrary effect. Sir ROBERT INGLIS was surprised and displeased at the course taken by Ministers. Mr. O'CONNELL was glad that the bill had been treated in so unce- remonious a way by Lord John ; and wished there had been any still more unceremonious a method of getting rid of it. It was "an insult to Ireland."

Mr. Ihsneetz reproached Ministers with the failure of their mea-

Mires.

Sir HUSSEY VIVIAN and Mr. ASHTON YATES thought that the bill had met with the fate it merited.

The amendments were ordered to be considered that day three months ; the bill, with the amendments, and the Lords' "reason!," to be printed.

M ISCELLA NEOCS.

THE bum TITHE BILL was read a third time by the Lords cn Thursday, and passed, after a protest from Lord CLANCARTY.

THE POST .OFFICE BILT. was opposed by the Duke of Riciatroren, and thrown out, on the motion for the second reading, by 32 to 35.

CUSTODY OF INFANTS BILL. Lord LYNDHURST gave notice, that he should reintroduce this bill next session.

PRISONS Bier.. Lord Chancellor COTTENHAM, on Monday, moved the second reading of this bill. The M irquis of SALISBURY moved that it be read that day three months. He especially objected to the providon for allowing clergymen not of the Established Church to be chaplains to prisons. Besides, there had not been sufficient time given to consider the measure. Lord levennunee complained of the great power the bill would give to the Secretary of State— It would enable the Secretary of State to establish solitary imprisonment in every prison in th:s country. This could scarcely be done in any prison now built; so that an unlimited power was given to the Secretary of State over the prisons of the country. By the I nv as it at present stood, the Secretary of State could alter rules and regulations; and by this law solitary confinement could he established in every prison in which he might think proper to establish it. That was an augmentation of power which had never before been given to any individual. He did not say that solitary confinement was not proper, but it was questionable ; it was a 'natter disputed, and the controversy was still going ou in America. Ile never would consent to vest in the Secretary of State the power of establishing solitary confinement in every place he pleased. He also looked to the enormous expense which would be caused by this bill ; and therefore he thought, that a matter of such importance ought not to he passed without an inquiry before a Committee above stairs, and without the most mature consideration.

Lord BROUGHAM, Lord CitrettesTen, the Duke of RICHMOND, and the Loan CHANCELLOR, wished the bill to go into Committee. Lord WHARNCLIFFE and the Earl of Wiceeow spoke on the other side.

On a division, the bill was thrown out, by a vote of 33 to 32.

TREATY WITH TIIE KING OF OUDE. Lord BROUGHAM asked Lord Glenelg, on Monday, whether lie had army objection to produce a treaty signed by the King of Oude, amid binding himself to pay seventeen lacs

of rupees to this country ? Lord GLENELG said, that as the treaty had not been ratified, and the President of the Board of Control had on that account declined to produce it in the House of Commons, and that House had decided not to press for it, he should also be compelled

to refuse the production of the treaty. Lord ELLENBOROUGII said, that ratification by this country was not necessary : the assent of the Governor-General of India alone was required. Lord BROUGHAM contended, that no reason could be assigned for the non. production of the treaty, unless it were contended that Parliament had no right to inquire into and control the govemninent of British pos- sessions in India. lie understood that the treaty had been obtained in fulfilment of a promise by the King of Omit', when in duresse, to sign any treaty which 'night be revered. The Marquis of LANS- DOWNE had great pleasure in stating, that the Governor-General of India, as soon as lie was informed of the manner in which the treaty had been made, expressed his disapprobation of it, and caused it to be

signified to the King of Oude that it should not be censidered binding upon him in any way. here the conversation dropped.

BENEFICES PLURALITY Bite. The House of Commons, on Mon- day, considered the Lords' amendment's. The only important dis- agreement was to the clause which allowed clergymen to hold two livings in certain eases. The bill as sent up from the Commons pro. vided, that no clergyman should hold two livings either of which exceeded in value 150/. per annum. The Lords raised the sum to 3001.; but on the motion of Mr. AGLTONLY, the sum of l.54.J1, was testored. A Cummittre w u ill:pointed to colter with tIm Lu rd on the heed- ] )wea amend met t.

IlAcKsrr C.otarac.r:s Dom. The Commons agreed to the Lorde• amendments on this hill.

Previous page

Previous page