Move over, Monet-maniacs Mark Glazebrook argues for abstract painting to

be studied with the same fervour as Impressionism n 30 January 1999, not long after the Royal Academy had mounted its second Monet exhibition, The Spectator published my first exhibition review. It was about a renewal of Cubism in the sculpture of Ivor Abrahams and began as follows: 'The end of a century, like a wedding, notoriously calls for something new. A millennium apparently calls for New Impressionism, although in a recent speech at the Royal Academy Gordon Brown made a special point of not claiming Monet for New Labour, despite his admiration for the great man's credentials, such as his stance on the Dreyfus case.'

We had yet to experience Monet 3 and various subsequent shows, at the RA and the National Gallery, for example, in which the magic turnstile word Impressionism featured, but my glancing reference to Monet 2 provoked a response from Frank Johnson, The Spectator's editor. The queues of apparent Monet-maniacs forming like sheep outside Burlington House had puzzled and irritated him a little. He wondered if I would write an article attacking Impressionism.

I knew how he felt. Although a Monet haystack is more complex and systematically less standardised than a beefburger, Impressionism had already been dubbed `the McDonald's of the art world'. The word Impressionism has been stretched to breaking point and exploited for decades by galleries and auction houses. Yet over a century ago had not Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Seurat achieved closure over the search by Monet, Sisley and others to register those charming, evanescent effects of light which became the essence of Impressionism, thereby earning their Post-Impressionist tag?

Hadn't this particular Big Four moved on to explore weightier problems, new methods of registering volume on a flat surface, new pictorial architecture, Symbolism, expressive pigment, Divisionist techniques and more exotic locations? And hadn't their discoveries in turn opened up new vistas and countless isms?

Wasn't it, or rather isn't it, about time therefore for popular taste to achieve closure, move on and become Post-Impressionist too? Should not cultural institutions lead public taste forward — or at the very least away from Renoir's chocolate-boxy children's cheeks and Monet's pretty poppies and the vulgar lilies he did when his eyesight faltered? The answer is a resounding yes, but in what direction should public taste be led? Should it be led into a tent by Tracey Emin, for example, or is there a somewhat more spiritual option? (A little thought will produce a rather obvious candidate to replace or at least to match Impressionism.) In the event I declined Frank Johnson's offer of a chance to pour scorn on Impressionism for a number of reasons. Sneering at popular taste should not be a critic's priority, and a Monet show in Burlington House was neither the time nor the place for an attack on Impressionism. As Chancellor Brown pointed out at the time — he even made a pun featuring the words Monet and money — the Royal Academy is proudly independent and doesn't ask the Treasury for the latter. As regards Monet himself, American Abstract Expressionism had created an awareness that there was more to his work — his brushwork, for example — than even his own contemporaries among painters had realised.

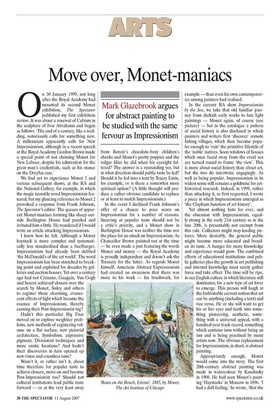

In the current RA show Impressionists by the Sea, we take that old familiar journey from darkish early works to late light paintings — Monet again, of course (see picture) — but in the catalogue a pattern of social history is also disclosed in which painters and writers first 'discover' remote fishing villages, which then become popular enough to 'ruin' the primitive lifestyle of the 'noble' natives. Soon windows of houses which once faced away from the cruel sea are turned round to frame 'the view'. This is more about social history than about art, but the two do intertwine engagingly. As well as being popular, Impressionism in its widest sense still remains a goldmine for arthistorical research. Indeed, in 1999, rather than attacking it, as first requested, I wrote a piece in which Impressionism emerged as `the Clapham Junction of art history'.

Appropriately enough, Monet would come into the story. The first 20th-century abstract painting was made in watercolour by Kandinsky in 1908. He had seen Monet's painting 'Haystacks' in Moscow in 1896. 'I had a dull feeling,' he wrote, 'that the object was lacking in this picture ... Painting took on a fairytale power and splendour; and, albeit unconsciously, objects were discredited as an essential element within the picture.' In other words, as Reinhard Zimmermann put it in his essay in Tate Modern's 2006 Kandinsky catalogue, 'So it was French Impressionism that first gave Kandinsky at least an approximate notion of what abstract art might look like.'

Moscow was home to several major abstract painters in the early 20th century. Abstract painting in Paris between the wars and in New York in the Forties and Fifties is famous, but there are many other centres worldwide, from Washington to St Ives. The abstract art of South America and the work of artists living in the Far East are now rewarding the attentions of international collectors. New figuration deserves study too. In England there have been successive waves of abstract painting. Vorticists such as Wadsworth, members of Abstraction-Creation such as Nicholson, the Constructionist movement centred around Pasmore and the Situationist artists of the early Sixties such as Hoyland have all been part of important group movements as well as being remarkable individuals. Kandinsky tried to justify his pioneering abstraction by using music as an analogy. That's no longer necessary. Abstract painting can stand on its own. Let's study it with the intensity that has been devoted to Impressionism.

Previous page

Previous page