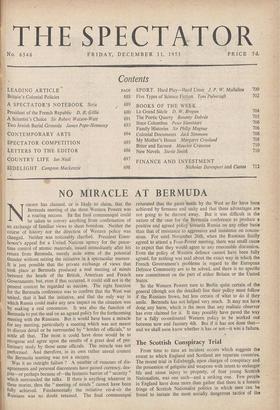

NO MIRACLE AT BERMUDA

NOBODY has claimed, or is likely to claim, that the Bermuda meeting of the three Western Powers was a roaring success. Its flat final communiqué could be taken to convey anything from confirmation of an exchange of familiar views to sheer boredom. Neither the course ' of history nor the direction of Western policy was changed. Neither was noticeably clarified. President Eisen- hower's appeal for a United Nations agency for the peace- time control of atomic materials, issued immediately after his return from Bermuda, merely stole some of the potential thunder without seizing the initiative in a spectacular manner. It is just possible that the private exchange of views that took place at Bermuda produced a real meeting of minds between the heads of the British, American and French Governments; but, even if that occurred, it could still not in the present context be regarded as success. The right function for the Bermuda conference was to confirm that the West was ' united, that it had the initiative, and that the only • way in which Russia could make any new impact on the situation was by making a real concession. It was also the function of Bermuda to put the seal on an agreed policy for the forthcoming meeting with the Russians. But it would hay.e been a miracle for any meeting, particularly a meeting which was not meant to discuss detail or be surrounded by " hordes of officials," to settle all that. The most it could have done would be to recognise and agree upon the results of a great deal of pre- liminary study by those same officials. The miracle was not Performed. And therefore, in its own rather unreal context the Bermuda meeting was not a success.

Was it an outright failure ? A number of rumours of dis- agreements and personal discontents have gained currency, des- pite—or perhaps because of—the fantastic barrier of " security " which surrounded the talks. If there is anything whatever in these stories, then the " meeting of minds" cannot haye been fully achieved. Fundamentally the initiative vis-a-vis the Russians was no doubt retained. The final communiqué reiterated that the gains made by the West so far have been achieved by firmness and unity and that these advantages are not going to be thrown away. But it was difficult in the nature of the case for the Bermuda conference to produce a positive and agreed policy towards Russia on any other baSis than that of resistance to aggression and insistence on conces- sions. For until November 26th, when the Russians finally agreed to attend a Four-Power meeting, there was small cause to expect that they would agree to any reasonable discussion. Even the policy of Western defence cannot have been fully agreed, for nothing was said about the exact way in which the French Government's problems in regard to the European Defence Community are to be solved, and there is no specific new commitment on the part of either Britain or the United States.

So the Western Powers turn to Berlin quite certain of the general (though not the detailed) line their policy must follow if the Russians frown, but less certain of what to do if they smile. Bermuda has not helped very much. It may not have done. any harm, which is the most that any realistic observer has ever claimed for it. It may possibly have paved the way for a fully co-ordinated Western policy to be worked out between now and January 4th. But if it has not done that—. and we shall soon know whether it has or not—it was a failure.

Previous page

Previous page