Not sparing the horses or the troopers

Philip Warner

A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH CAVALRY, VOLUME V, 1914-1919 by the Marquess of Anglesey Leo Cooper, £40, pp. 388 Like the other volumes in this admirable series, this account of the cam- paign in Egypt, Palestine and Syria is both sound history and absorbing reading. There is, as we have come to expect, much anec- dotal material as well as clear maps and original illustrations, but the unusual fea- ture here is that the cavalry is a different species. The famous regular cavalry regi- ments do not appear: the action, and there is plenty of it, is provided by Australians, New Zealanders, Indians, and British Yeomanry (of which no less than 18 regi- ments distinguish themselves). All in all, a mixed bag, but directed and led by Allenby and a few talented subordinates they inflict- ed a thumping defeat on a courageous Turkish army commanded by the experi- enced and competent German general, Liman von Sanders, who already had the victory at Gallipoli to his credit, and was also a cavalryman by profession.

The Turks had been repulsed from Egypt in 1915 but had humiliated the Allies at Gallipoli. They had captured a British divi- sion at Kut but subsequently lost Baghdad. In 1917 a special force — the Yilderim was being trained and commanded by the German General Falkenhayn, who planned to recapture Baghdad and Egypt, denying the British the use of the Suez Canal and Mesopotamian oil supplies. If the British were defeated once more by the Turks, there was a good chance that many Moslems in Egypt, Persia and even India would stir up widespread trouble. To settle the Turkish threat once and for all it was necessary to inflict a crushing defeat on their armies and also capture the presti- gious Holy City, Jerusalem. Although a symbolic Christian city, Jerusalem ranks closely behind Mecca on the list of places sacred to Islam.

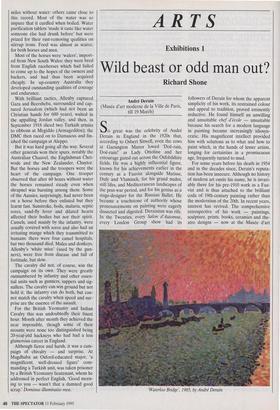

General Edmund Allenby, 'The Bull', was appointed in July 1917 to accomplish this arduous task. At once he began to train the Desert Mounted Corps; drawn from Australian, New Zealand, Indian and British Yeomanry units, it was the largest tactical force of cavalry ever to operate under a single command and its feats, such as regular marches of 60 miles a day in temperatures of up to 125 Fahrenheit, seem almost incredible. One regiment, the Worcestershire Yeomanry, marched 90 miles without water: others came close to this record. Most of the water was so impure that it curdled when boiled. Water purification tablets 'made it taste like water someone else had drunk before' but were prized for their rust-removing qualities on stirrup irons. Food was almost as scarce, for both horses and men.

Most of the horses were `walers', import- ed from New South Wales: they were bred from English racehorses which had failed to come up to the hopes of the owners and backers, and had thus been acquired cheaply. In up-country Australia they developed outstanding qualities of courage and endurance.

With brilliant tactics, Allenby captured Gaza and Beersheba, surrounded and cap- tured Jerusalem (which had not been an Christian hands for 600 years), waited in the appalling Jordan valley, and then, in September 1918 sliced two Turkish armies to ribbons at Megiddo (Armageddon); the DMC then raced on to Damascus and fin- ished the campaign at Aleppo.

But it was hard going all the way. Several other generals won their spurs, notably the Australian Chauvel, the Englishman Chet- wode and the New Zealander, Chaytor. But the horses and the troopers were the heart of the campaign. One trooper observed that after 60 hours without water the horses remained steady even when shrapnel was bursting among them. Some of the Aussies, surprisingly, had never been on a horse before they enlisted but they learnt fast. Sunstroke, boils, malaria, septic sores, sand-fly fever and dilated hearts affected their bodies but not their spirit. Camels, used mainly by the infantry, were usually covered with sores and also had an irritating mange which they transmitted to humans: there were four camel hospitals, but two thousand died. Mules and donkeys, Allenby's 'white mice' (used by the gun- ners), were free from disease and full of fortitude, but slow.

The cavalry did not, of course, win the campaign on its own. They were greatly outnumbered by infantry and other essen- tial units such as gunners, sappers and sig- nallers. The cavalry can win ground but not hold it; the infantry can do both, but can- not match the cavalry when speed and sur- prise are the essence of the assault.

For the British Yeomanry and Indian Cavalry this was undoubtedly their finest hour. Month after month they achieved the near impossible, though some of their mounts were none too distinguished being 20-ye-gold hackneys who had had a less glamorous career in England.

Although fierce and harsh, it was a cam- paign of chivalry — and surprise. At Magdhaba an Oxford-educated major, 'a magnificent, well-dressed figure' com- manding a Turkish unit, was taken prisoner by a British Yeomanry lieutenant, whom he addressed in perfect English, 'Good morn- ing to you — wasn't that a damned good scrap.' Dominus illuminatio mea.

Previous page

Previous page