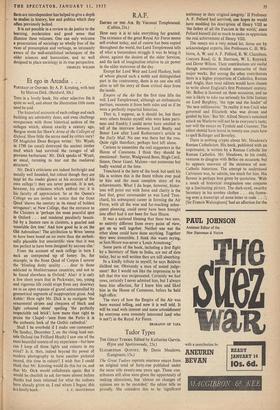

Tudor Types

The Great Tudors reprints nineteen essays from an original total of forty-one published under the same title twenty-one years ago. Those con- tributors still alive were given the opportunity of making alterations, but 'almost no changes of opinion are to be recorded,' the editor tells us proudly. She considers this to be 'significant

testimony to their original integrity.' If Professor A. F. Pollard had survived, one hopes he would have modified his description of Henry VIII as 'the father of all the Fascists in the world,' since Pollard himself did so much to make us appreciate the real achievement of Henry VIII.

The essays are a very mixed lot. Some are by acknowledged experts, like Professors C. H. Wil-

liams, A. W. and A. F. Pollard, R. W. Chambers, Conyers Read, G. B. Harrison, W. L. Renwick and Dover Wilson. Their contributions are useful though sometimes slender summaries of their major works. But among the other contributors there is a higher proportion of Catholics, Roman and Anglo, than most editors would have chosen to write about England's first Protestant century. Mr. Belloc is licensed on these occasions, and no one is likely to take too seriously his little fantasy on Lord Burghley, 'the type and the leader' of 'the new millionaires.' In reality it was Cecil who governed and Elizabeth who was driven and guided by him.' But Mr. Alfred Noyes's sustained attack on Marlowe will not be to everyone's taste; nor will the essays on Tyndale and Cranmer. The editor should have learnt in twenty-one years how to spell Bullinger and Beverley.

There is nothing crypto about Mr. Meadows's Roman Catholicism. His book, published with an imprimatur, is written by a Roman Catholic for Roman Catholics. Mr. Meadows, to his credit, ventures to disagree with Belloc on occasion; but he appears unaware of the existence of non- Catholic historians. The attempt to understand Calvinism was, he admits, too much for him. His flavour is perhaps best given by quotation. 'With a touch of historical imagination one conjures up a fascinating picture. The dark-eyed, swarthy Secretary in his sombre clothes . . . sits frown- ing over a transcript of some letter in code . . .'; [Sir Francis Walsingham] 'had an affection for the

English hawthorn. Did its toughness and its thorns appeal to the Calvinist in him, or was it that the Lady Ursula and young Frances loved the sweet smell of the blossom?' One suspects that he [John Dee) had good hands, perhaps with grace- ful, tapering fingers. They were a passport to the queen's approval' (i.e., they would have been if he had had them. But had he?).

Nevertheless, though he is discursive and repetitive, Mr. Meadows writes with gusto and enjoyment. Walsingham was too tough a subject foi him altogether, and so the longest and most ambitious essay in the book is a total failure. But he is interesting on Robert Parsons, Bursar of Balliol and later seditious Jesuit; and in the last three essays, where apologetics are forgotten, Mr. Meadows succeeds in being quite entertaining. They deal with John Dee, the astrologer, who shared illusions and wives with his medium; Mary Frith, the gangster and vice queen who was an enthusiastic royalist during the civil war; and Sir John Harington, Queen Elizabeth's godson and the inventor of the water-closet.

CHRISTOPHER HILL

Previous page

Previous page