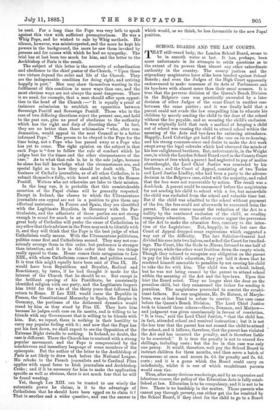

SCHOOL BOARDS AND THE LAW COURTS.

THAT still-vexed body, the London School Board, seems to be in smooth water at last. It has, perhaps, been more unfortunate in its attempts to settle questions as to the extent of its powers than almost any other subordinate authority in the country. The county justices and the stipendiary magistrates have alike been banded against school Boards ; and even the Judges of the High Court apparently endeavoured to make nonsense of its Acts of Parliament and its bye-laws with almost more than their usual acumen. It is true that the perverse decision of the Queen's Bench Division in the Belgrave case was practically overruled by a later decision of other Judges of the same Court in another case between the same parties ; and it was finally held that a parent could not evade the law compelling him to educate his children by merely sending the child to the door of the school without the fee payable, and so securing the child's exclusion. It was originally held that such a method of keeping a child out of school was causing the child to attend school within the meaning of the Acts and bye-laws for enforcing attendance. Happily, Lord Coleridge got hold of the case on its re-hearing, and his strong common-sense and desire to make the Act work swept away the legal cobwebs which had obscured the minds of his less enlightened brethren. But, unfortunately, in the Wright case, in which the London School Board sued in the County Court for arrears of fees which a parert had neglected to pay of malice aforethought, the Lord Chief Justice was overruled by his brethren ; and the Court of Appeal, consisting of two Tories and Lord Justice Lindley, who had been a party to the adverse decision in the Belgrave case, sided with the majority, and ruled that the fees were not recoverable by action. The result was a dead-lock. A parent could be summoned before the magistrates for not sending his child to school with a fee, but meanwhile the child was excluded from the school and valuable time lost. But if the child was admitted to the school without payment of the fee, the fees could not afterwards be recovered from the parent. The one course meant the reduction of the Act to a nullity by the continued exclusion of the child, so evading compulsory education. The other course mgant the perversion of the Act to make the education free, contrary to the inten- tion of the Legislature. But, happily, in the last case the Court of Appeal dropped some expressions which suggested a way out of the difficulty. The late Solicitor-General had divided his case into two halves, and asked the Court for two find- ings. The Court, like the Gods to 2Eneas, listened to one half of his prayer, while the other went fruitless down the empty winds. Though they refused to recognise any obligation on the parent to pay for his child's education, they yet laid it down that he rendered himself amenable to penalties by not causing his child to take the fee with him. The child was in school, indeed, but he was not being caused by the parent to attend school within the meaning of the Act and the bye-laws. Upon this hint the Board acted. They no longer shut the door on the penniless child, but they summoned the father for sending it penniless. The magistrates proceeded to convict the recalci- trant fathers. But one magistrate, Mr. De Rutzen, of Maryle- bone, was at last found to refuse to convict. The case came before the Queen's Bench Division. The Lord Chief Justice took to himself three others—Grove, Denman, and Mathew— and judgment was given unanimously in favour of conviction. "It is true," said the Lord Chief Justice, "that the child has,

in fact, attended school and received instruction ; but it is not the less true that the parent has not caused the child to attend the school, and it follows, therefore, that the parent has violated the Act and has incurred the penalty, and is therefore liable to be convicted." It is true the penalty is not to exceed five shillings, including costs ; but the fee in this case was only one penny. It would, therefore, well pay the School Board to instruct children for three months, and then serve a batch of summonses at once and secure 2s. 6d. for penalty and 2s. 6d. costs ; and it is a game which the Board could carry on indefinitely, whilst it is one of which recalcitrant parents would soon tire.

Thus, after many devious wanderings, and by an expensive and laborious course, the policy of the Education Acts is fully estab- lished at law. Education is to be compulsory, and it is not to be free. There is no hardship in the matter. Those parents who cannot pay through poverty, can either get the fee remitted by the School Board, if they elect for the child to go to a Board School ; or they can get it paid by the Guardians, if they elect to send it to a Voluntary School. The question is not whether education should be free for all, though we do not think it should. It must, in any case, be wrong that it should be free or not at the election of the parents, and by an accidental omission or defect in expression in the Act of Parliament, instead of by the deliberate intention of the Legislature. If education were to be free, it would be made free for all, and must be made so after full and free discussion on that particular point by Parliament. Nor is it, perhaps, altogether undesirable in result that it is only by quasi-criminal proceedings that payment can in effect be enforced. It, may lead to some strange miscarriages. For instance, a case is now pending from the Hammersmith Police Court, in which a child, having spent the money which had been given it to pay the fee, was admitted to school on Monday, but refused admission on Tuesday. The parent was summoned for not causing the child to attend school, i.e., with the fee. The summons was dismissed. A penal offence implies guilty intention. If the child was given the money to pay, and misappropriated it, there was no guilty mind on the part of the parent, whatever there might have been on the part of the child. But if this aberration on the part of the child became too frequent, the magistrate would presumably disbelieve that the child had been given the money to pay, or he could still convict the father for trusting an untrustworthy child. Meanwhile, in the generality of cases it is just as well that evading the Education Act—that is, de- clining to perform the duty of a parent in regard to education— should be placed on the same footing as declining to perform the duty of a parent in regard to nurture. Such a neglect of duty is a criminal neglect, and should be stigmatized as criminal. The Act contains ample exemptions in case of real inability to comply with its provisions, through poverty, illness, or distance from school. There is little real opposition to compulsory education among the real working-classes. Compulsory educa- tion was a working-class cry in the days of Chartism, and a Radical doctrine till 1870. The opposition now raised to it is, except by a few "faddists," the interested opposition of a class who hate " light " in any form, and above all hate having to assist in the illumination of their neighbours. They must now carry their opposition elsewhere than to the Law Courts. Lord Coleridge has cleared them out of that field.

Previous page

Previous page