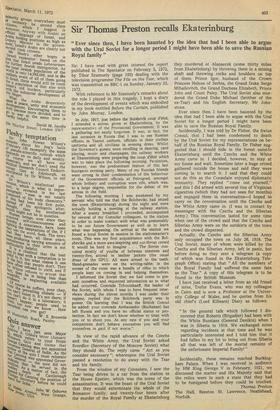

Sir Thomas Preston recalls Ekaterinburg

"Ever since then, I have been haunted by the idea that had I been able to argue with the Ural Soviet for a longer period I might have been able to save the Russian Royal family"

Sir: I have read with great interest the report published in The Spectator on February 5, 1972, by Tibor Szamuely (page 193) dealing with the television programme The File on the Tsar, which was transmitted on BBC-1 on Sunday, January 23, 1972.

With reference to Mr Szamuely's remarks about the role I played in this tragedy, I kept a diary of the development of events which was embodied in my book entitled Before the Curtain, published by John Murray, London.

In July, 1917, just before the Bolshevik coup d'etat, I attended a soiree, given at Ekaterinburg, by the repre-ientativ a of the Provisional Government. It was a gathering not easily forgotten. It was, in fact, the last occasion in Russia that I was to see Russian officers in Tsarist uniform, officials in their civilian uniforms and all civilians in evening dress. Whilst the Governor's guests were revelling in dancing, card playing, music and champagne, the railway workers at Ekaterinburg were preparing the coup d'6tat which was to take place the following morning. Pe3simism, however, was the predominant feature of this last bourgeois evening party. Many of my Russian friends were strong in their condemnation of the behaviour of the Government officials at Petrograd, amongst whom bribery and corruption were rife, which was, to a large degree, responsible for the defeat of the armies in the field.

The following morning I was awakened by my servant who told me that the Bolsheviks had seized the town (Ekaterinburg) during the night and were actually holding a meeting at the railway station. After a scanty breakfast I proceeded, accompanied by several of my Consular colleagues, to the station in order to make contact with what was presumably to be our future Government as well as to learn what was happening. On arrival at the station we found a local Soviet in session in the stationmaster's room. This was my first acquaintance with the Bolsheviks and a more awe-inspiring and cut-throat crowd it would be hard to imagine . . . The Soviet consisted mostly of youths of between nineteen and twenty-five, attired in leather jackets (the usual dress of the GPU). All were armed to the teeth. Hand-grenades were on the writing-table; in the corner of the room was a bundle of rifles to which people kept on coming in and helping themselves.

I informed the Soviet that we had come to present ourselves and requested information as to what had occurred. Comrade Tchoutskaeff, the leader of the Soviet, with whom I was to have frequent interviews during the eleven months I was under their regime, replied that the Bolshevik party was in power. On learning that I was the British Consul he added: your comrade Ambassador (Buchanan) has left Russia and you have no official status or protection. In fact we don't know whether to treat with you or to shoot you. At any rate if you and your compatriots don't behave yourselves you will find yourselves in gaol if not worse."

In view of the rapid advance of the Czechs and the White Army, the Ural Soviet asked Sverdlov (Secretary of the Moscow Soviet) what they should do. The reply came "Act as you consider necessary "; whereupon the Ural Soviet passed a resolution to do away with the Tsar and his family.

From the window of my Consulate, I saw the Tsar being driven in a car from the station to the House Epatiev, which was the scene of the assassination. It was the boast of the Ural Soviet that they would exterminate the whole of the Romanov family, and twenty-four hours after the murder of the Royal Family at Ekaterinburg they murdered at Alapaecsk (some thirty miles from Ekaterinburg) by throwing them in a mining shaft and throwing rocks and boulders on top of them, Prince Igor, husband of the Crown Princess Helene of Serbia, the Grand Duke Serge Mihailovitch, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Prince John and Count Paley. The Ural Soviet also murdered the Grand Duke Michael (brother of the ex-Tsar) and his English Secretary, Mr Johnstone.

Ever since then I have been haunted by the idea that had I been able to argue with the Ural Soviet for a longer period I might have been able to save the Russian Royal Family.

Incidentally, I was told by Dr Fisher, the Swiss Consul, that I had been condemned to death by the Ural Soviet for my representations on behalf of the Russian Royal Family. Dr Fisher suggested that I should hide in the forest outside Ekaterinburg until the Czechs and the White Army came in. I decided, however, to stay at my house and wait. Sometime later a huge crowd gathered outside the house and said they were coming in to search it. I said that they could not do this as the Consulate enjoyed diplomatic immunity. They replied "come out yourself," and this I did armed with several tins of Virginian cigarettes (which they had not seen for months) and engaged them in conversation—I hoped to carry on the conversation until the Czechs and the White Army came in. (I was in contact by messenger with the Czechs and the Siberian Army.) This conversation lasted for some time when one of the crowd said that the Czechs and Siberian Army were on the outskirts of the town and the crowd dispersed.

Actually, the Czechs and the Siberian Army only occupied the town on July 26, 1918. The Ural Soviet, many of whom were killed by the Czechs and the Siberian Army, left in panic, but before doing so they sent a telegram (a copy of which was found in the Ekaterinburg Telegraph Office) stating that "All the members of the Royal Family had suffered the same fate as the Tsar." A copy of this telegram is to be found in the British Museum.

I have just received a letter from an old friend of mine, Trefor Evans, who was my colleague in Cairo and is now a Professor at the University College of Wales, and he quotes from his old chief's (Lord Killearn) Diary as follows: "In the general talk which followed I discovered that Roberts (Brigadier) had been with the White Russians (General Denikin) when I was in Siberia in 1919. We exchanged notes regarding incidents at that time and he was particularly interested and I told him that it had fallen to my lot to bring out from Siberia all that was left of the mortal remains of the unfortunate Imperial Family!"

Incidentally, these remains reached Buckingham Palace. When I was received in audience by HM King George V in February, 1921, we discussed the matter and His Majesty said that the relics were in such a state that they had to be fumigated before they could be touched. Thomas Preston The Hall, Beeston St. Lawrence, Neatishead, Norfolk.

Previous page

Previous page