DIARY

As a committed and consistent pro- semite — even to the point of defending Israel's incursions into Lebanon — I have to admit that the Jews come out of the Bitburg business very badly. Naturally everbody decent understands the depth of their feelings about the Holocaust. But to use every devious trick of moral blackmail to try to wreck President Reagan's wholly laudable attempt, 40 years after the war, to do justice to Germany's miraculous regen- eration seems, to me quite inexcusable. Cannot the Jews realise the harm that would have been done to the free world by continuing to treat the Germans as perma- nent pariahs? Are they unable to appreci- ate the absolute priority that ought to be given to integrating Western Germany into Western Europe? For almost half a century in the Middle East, Western feelings of guilt have prodded us — quite rightly in my view — into supporting Israel, very often disastrously against Britain's own best in- terests. But for the Jews to try to use this same kind of moral blackmail to compel the West to allow its foreign policy to be equally distorted by guilt in regard to the very heartland of Western Europe, that really is over the odds. The Arabs have been complaining for years that the Jews are blind to any other good cause except their own. After Bitburg many of us Pro-semites will be slightly less eager to deny this charge than we were before.

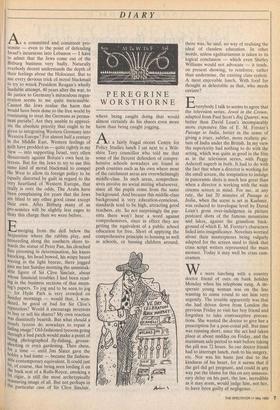

Emerging from the dell below the Serpentine where the rabbits play, and Proceeding along the southern shore to- wards the statue of Peter Pan, his clenched fists pistoning in determination, his knees knocking, his head bowed, his wispy beard Waving in the light breeze, there jogged Past me last Sunday morning the unmistak- able figure of Sir Clive Sinclair, about Whose financial troubles I had been read- ing in the business sections of that morn- lag's papers. To jog and to be seen to jog --- for Hyde Park is very crowded on Sunday mornings -- would that, I won- dered, be good or bad for Sir Clive's reputation? Would it encourage investors to buy or sell his shares? My own reaction was dinstinctly bearish. But what should a trendy tycoon do nowadays to repair a fading image? Old-fashioned tycoons going through a bad patch would make a point of being photographed fly-fishing, grouse- shooting or even gardening. Then chess, [Or a time — until Jim Slater gave the hobby a bad name — became the fashion- able contemporary equivalent. It could just he, of course, that being seen lording it on the back seat of a Rolls-Royce, smoking a fat cigar, is still the most archetypically reassuring image of all. But not perhaps in the particular case of Sir Clive Sinclair, PEREGRINE WORSTHORNE

where being caught doing that would almost certainly do his shares even more harm than being caught jogging.

At a fairly frugal recent Centre for Policy Studies lunch I sat next to a Wilt- shire Tory councillor who told me that some of the fiercest defenders of compre- hensive schools nowadays are found in posh counties such as his own where most of the catchment areas are overwhelmingly middle-class. In such areas, comprehen- sives involve no social mixing whatsoever, since all the pupils come from the same background. And because this middle-class background is very education-conscious, standards tend to be high, attracting good teachers, etc. So not surprisingly the par- ents there won't hear a word against comprehensives, since in effect they are getting the equivalent of a public school education for free. Short of applying the comprehensive principle to housing as well as schools, or bussing children around,

there was, he said, no way of realising the ideal of classless education. In other words, unless egalitarianism is taken to its logical conclusion — which even Shirley Williams would not advocate — it tends, on present showing, to reinforce, rather than undermine, the existing class system. A most enjoyable lunch. With food for thought as delectable as that, who needs caviare?

Everybody I talk to seems to agree that the television series, Jewel in the Crown, adapted from Paul Scott's Raj Quartet, was better than David Lean's incomparably more expensive film of E. M. Forster's Passage to India, better in the sense of giving a truer, subtler, more realistic pic- ture of India under the British. In My view the superiority had nothing to do with the acting, which was quite as good in the film as in the television series, with Peggy Ashcroft superb in both. It had to do with the fact that when a director is working for the small screen, the temptation to indulge in panoramic shots is much less great than when a director is working with the wide cinema screen in mind. For me, at any rate, the last 20 minutes of Passage to India, when the scene is set in Kashmir, was reduced to travelogue level by David Lean's gross over-indulgence in picture postcard shots of the famous mountains and lakes, against the grandiose back- ground of which E. M. Forster's characters faded into insignificance. Novelists worried about their masterpieces being vulgarly adapted for the screen used to think that crass script writers represented the main menace. Today it may well be crass cam- eramen.

We were lunching with a country doctor friend of ours on bank holiday

Monday when his telephone rang. A de- sperate young woman was on the line wanting to come round to see him very urgently. The trouble apparently was that she had driven down from London the previous Friday to visit her boy friend and forgotten to take contraceptive precau- tions. She wanted the doctor to give her a prescription for a post-coital pill. But time was running short, since the act had taken place at about midday on Friday, and the maximum safe period to wait before taking the pill was 72 hours. So our doctor friend had to interrupt lunch, rush to his surgery, etc. Nor was his haste just due to the kindness of his heart, for it seems that if the girl did get pregnant, and could in any way put the blame for this on any unneces- sary delay on his part, the law, incredible as it may seem, would judge him, not her, to have been guilty of negligence.

Previous page

Previous page