REVIEW OF THE ARTS

Theatre

The Edna O'Brien Show

Kenneth Hurren

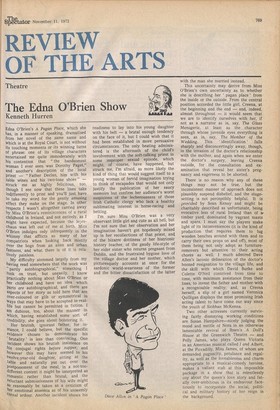

Edna O'Brien's A Pagan Place, which she has, in a manner of speaking, dramatised from her novel of the same name and Which is at the Royal Court, is not without its touching moments or its winning turns of phrase: one of its village characters entertained me quite immoderately with his contention that "the handsomest woman I ever seen was Dorothy Paget," and another's description of the local Priest — "Father Declan, him with his table wines and his two-tone shoes" — struck me as highly felicitous, too, though I see now that these lines take indifferently to print and you'll just have to take my word for the gently amusing effect they make on the stage. In other respects I wasn't altogether carried away by Miss O'Brien's reminiscences of a rural Childhood in Ireland, and not entirely, as I /night have expected, because the leprechaun was left out of me at birth. Miss O'Brien indulges only infrequently in the Whimsy that afflicts so many of her compatriots when looking back mistily over the bogs from an alien and urban fastness, and what there is of it is relatively painless.

My difficulty stemmed largely from my having read somewhere that the work was partly autobiographical," something I took on trust, but uneasily. I know Practically nothing about Miss O'Brien or her childhood and have no idea which Parts are autobiographical, and there are aspects of her story as told here that are over-coloured or glib or symmetrical in Ways that may have to be accepted inreallife but cannot be permitted in fiction. I am dubious, too, about the manner in Which, having established some sort of credibility, she goes about bolstering it.

Her brutish, ignorant father, for instance, I could believe, but the specific evidence chosen to demonstrate his

• brutality' is less than convincing. One Incident shows his brutish insistence on his conjugal rights before supper, and however this may have seemed to his tWelve-year-old daughter, sitting at the table and naturally put out over the Postponement of the meal, in a not-toodifferent context it might be interpreted as romantic rather than brutal, and the reluctant submissiveness of his wife might as reasonably be taken as a criticism of her emotional anaemia as of his unseemly carnal ardour. Another incident shows his

readiness to lay into his young daughter with his belt — a brutal enough tendency on the face of it, but I could wish that it had been established in more persuasive circumstances. The only beating administered is the aftermath of the child's involvement with the soft-talking priest in some improper sexual episode, which might, of course, have happened, but struck me, I'm afraid, as more likely the kind of thing that would suggest itself to a young woman of fervid imagination trying to think of escapades that would not only justify the publication of her saucy memoirs but confirm her audience's worst suspicions of the lecherousness of those Irish Catholic clergy who lack a healthy sublimating interest in horse-racing and betting. I'm sure Miss O'Brien was a very observant little girl and cute as all hell, but I'm not sure that her observation and her imagination haven't got hopelessly mixed up in her recollections of that priest, and of the bizarre dottiness of her histrionic history teacher, of the gaudy life-style of her elder sister who returns pregnant from Dublin, and the frustrated bygone love of the village doctor and her mother, which picturesquely accounts at once for the sardonic world-weariness of the former and the bitter dissatisfaction of the latter with the man she married instead.

This uncertainty may derive from Miss O'Brien's own uncertainty as to whether she is describing her ' pagan place ' from the inside or the outside. From the central position accorded the little girl, Creena, at the beginning and the end — and, indeed, almost throughout — it would seem that we are to identify ourselves with her, if not as a narrator as in, say, The Glass Menagerie, at least as the character through whose juvenile eyes everything is seen, as in, say, The Member of the Wedding. This ' identification ' falls sharply and disconcertingly away, though, in the invasion of the doctor's relationship with the mother, and again when we enter the doctor's surgery, leaving Creena outside, for the consultation and examination that reveal her sister's pregnancy and eagerness to be aborted.

There is no reason why any of these things may not be true, but the inconsistent manner of approach does not plausibly suspend disbelief, and the stagesetting is not perceptibly helpful. It is provided by Sean Kenny and might be charitably described as unfortunate, being evocative less of rural Ireland than of atimber yard, dominated by vagrant masts and spars. I must say the players make light of its inconveniences (it 4s the kind of prod,uction that requires them to lug wooden benches around with them and to carry their own props on and off), most of them being not only adept as furnitureremovers but attentive to their acting chores as well. I much admired Dave Allen's laconic delineation of the doctor's boozed resignation to the village life, and the skill with which David Burke and Colette O'Neil contrived from time to time, with minimum assistance from their lines, to invest the father and mother with a recognisable reality; and, as Creena herself, a slip of a girl named Veronica Quilligan displays the most promising Irish acting talent to have come our way since the youth of Siobhan McKenna.

Two other actresses currently surviving fairly dismaying working conditions are Susan Hampshire—nicely judging the mood and mettle of Nora in an otherwise lamentable revival of lbsen's A Doll's House at the Greenwich Theatre — and Polly James, who plays Queen Victoria in an American musical called I and Albert, at the Piccadilly. Miss James, of whom are demanded pugnacity, petulance and regality, as well as the loveableness and charm appropriate to a musical-comedy heroine, makes a valiant stab at this impossible package in a show that is relentlessly coy about the queen's love story and fatally over-ambitious in its endeavour facetiously to incorporate the social, political and military history of her reign in the background.

Previous page

Previous page