Another Spectator's Notebook

The Government reshuffle gives me an opportunity to make some more com plaints. I heard the news after watching Cliff Michelmore interview Peter Walker on A Chance to Meet on Sunday. At the end of the interview Walker had just answered a question about industry When Michelmore turned to him and said, " Well, you will now have a chance to get involved in industry again, since we have just heard that you are to be the new Secretary of State for Trade and Industry." I hasten to add that I have no complaint against the Michelmore programme: there was nothing they and Peter Walker could do but go ahead with the interview as it was, given that the reshuffle news was clearly embargoed until the time it ended. My complaint is about the subsequent radio and television coverage of the shuffle. which I heard and saw.

Soft pedal shuffle

I expected a news flash on BBC after the Michelmore programme, but it did not appear. I then turned on the wireless, hoping for a flash at seven o'clock. It came, and we learned what the main Cabinet changes were, and that there had been a total of nineteen moves. Later in the evening I watched the ITN news. To Illy astonishment, I learned no more than I had heard on the wireless news flash, plus some abstract details ' — that the Ulster Office had been beefed up, for example. On Monday morning, as usual, I listened to the whole of BBC's normally excellent Today programme. I was not much wiser at nine o'clock than I had been at seven; and what I did discover that was extra came from an interview between Robert Robinson and Tony Shrimsley of the Sun. John Snagge has said the quality of

13C radio news is declining, but this is ridiculous.

Blake and Stevas

Two brand new appointments I found especially pleasing. The first was of Peter Blaker, the dashing and quick-witted member for Blackpool North, to the Ministry of Defence: the second was that of Norman St John Stevas to Education and Science. Blaker was one of the most effective scourges of Harold Wilson at Prime Minister's Questions under the Labour Government, and has a mind like a razor, and a wit to match. There is a certain aloofness about him, often unpopular with his colleagues, and some have described him as lightweight. He has, however, always been one of my own favourite political horses, and I am now Willing to invest a little more on him. Stevas is a much more uncertain quantity. He is flamboyant in an age of dullness and, on his day, a brilliant orator. Also, he has very sound views about education, of a distinctly conservative kind. The difficulty is that his temperament is uncertain and, in the joy of his own rhetoric, he sometimes confuses words with their meaning. But he has ability, and he will liven things up considerably. He will. I feel, be either an outstanding success or a total failure.

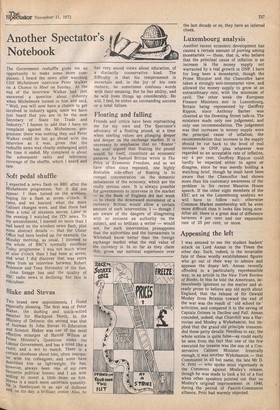

Floating and falling

Friends and critics have been reproaching me for my own and The Spectator's advocacy of a floating pound, at a time when sterling values are plunging deeper and deeper on the exchange market. It is necessary to emphasise that no ' floater ' has ever argued that floating the pound would, by itself, constitute an economic panacea. As Samuel Brittan wrote in The Price of Economic Freedom, and as we have often since repeated, one highly desirable side-effect of floating is to compel concentration on the domestic imbalances of the economy, which are the really serious ones. It is always possible for governments to intervene in the market — as the Bank of England did last week — to check the downward movement of a currency. Brittan would allow a certain amount of such intervention. I — though I am aware of the dangers of disagreeing with so eminent an authority on the subject, and so brilliant a writer — would not, for such intervention presupposes that the authorities and the bureaucrats in Whitehall know better than the foreign eNchange market what the real value of the currency is. In so far as they claim this, given our national experience over

the last decade or so, they have an infernal cheek.

Luxembourg analysis

Another recent economic development has caused a certain amount of purring among

monetarists — those, that is, who believe that the principal cause of inflation is an increase in the money supply not

warranted by a real growth in GNP. I have

for long been a monetarist, though the Prime Minister and the Chancellor have taken a strongly anti-monetarist view, and allowed the money supply to grow at an extraordinary rate, with the minimum of cavil. The other week the European Finance Ministers met in Luxembourg, Britain being represented by Geoffrey

Rippon, since Anthony Barber was closeted at the Downing Street talk-in. The ministers made only one judgement, and only one recommendation. The judgement was that increases in money supply were the principal cause of inflation; the recommendation that increase in the supply should be cut back to the level of real increase in GNP, plus whatever was regarded as an acceptable rate of inflation, say 4 per cent. Geoffrey Rippon could hardly be expected either to agree or disagree, since he was merely holding a watching brief, though lie must have been aware that the Chancellor had shown more than his customary awareness of the problem in his recent Mansion House speech. If the other eight members of the EEC act on the Luxembourg analysis we will have to follow suit: otherwise Common Market membership will be even more difficult than it looks like being now. After all, there is a great deal of difference between 4 per cent and our expansion rate of 25 per cent, or more.

Appeasing the left

I was amused to see the student leaders' attack on Lord Annan in the Times the other day. Such, indeed, is the invariable fate of these woolly establishment figures who go out of their way to admire and appease the dopey left. Annan recently offended in a particularly reprehensible way, in an article in the New York Review of Books. In this he told the Americans, defencelessly ignorant on the matter and already prone to believe any old myth about England, that the release of Sir Oswald Mosley from Brixton toward the end of the war was the result of ' old school tie ' activities, and compared it to the saving of Captain Grimes in Decline and Fall. Annan conceded, indeed, that Churchill was a Harrovian and Mosley a Wykehamist, but implied that the grand old principle transcended these petty details. Needless to say, the whole notion is quite false—as could easily be seen from the fact that one of the few executed for treason was the son of a Conservative Cabinet Minister. Ironically enough, it was another Wykehamist — that Communist in all but name, the late Mr D. N. Pritt — who spoke most vigorously in the Commons against Mosley's release, though he was made to look a bit of a fool when other speakers pointed out that on Mosley's original imprisonment in 1940, during the period of Fascist-Communist alliance, Pritt had warmly objected.

Previous page

Previous page