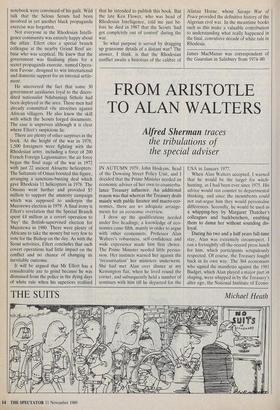

FROM ARISTOTLE TO ALAN WALTERS

Alfred Sherman traces

the tribulations of the special adviser

IN AUTUMN 1979, John Hoskyns, Head of the Downing Street Policy Unit, and I decided that the Prime Minister needed an economic adviser of her own to counterba- lance Treasury influence. An additional reason was that whereas the Treasury deals mainly with public finance and Macro-eco- nomics, there are no adequate arrange- ments for an economic overview.

I drew up the qualifications needed under five headings; a knowledge of eco- nomics came fifth, mainly in order to argue with other economists. Professor Alan Walters's robustness, self-confidence and wide experience made him first choice. The Prime Minister needed little persua- sion. Her instincts warned her against the `treasurisation' her ministers underw. ent. She had met Alan over dinner at my Kensington flat, when he lived round the corner, and subsequently held a number of seminars with him till he departed for the

USA in January 1977.

When Alan Walters accepted, I warned that he would be the target for witch- hunting, as I had been ever since 1975. His advice would run counter to departmental thinking, and since the incumbents could not out-argue him they would personaliSe differences. Secondly, he would be used as a whipping-boy by Margaret Thatcher's colleagues and backbenchers, enabling them to damn her without sounding dis- loyal.

During his two and a half years full-time stay, Alan was extremely circumspect. I ran a fortnightly off-the-record press lunch for him, which participants scrupulously respected. Of course, the Treasury fought back in its own way. The 364 economists who signed the manifesto against the 1981 Budget, which Alan played a major part in shaping, were whipped in by the Treasury's alter ego, the National Institute of Econo- mic and Social Research. But their pre- dicted doom failed' to materialise, and Alan refrained from crowing too loudly.

He and Mrs Thatcher worked well together. His writ ran much wider than macroeconomics and finance, extending to transport, energy, foreign debt, int. al. Where Treasury matters were concerned, the Prime Minister with his help made major policy, which Sir Geoffrey Howe and his team implemented and were given credit for. The arrangement worked well until Paddy Walters insisted on returning to Washington which she found more congenial. Sir Alan was obliged reluctantly to up sticks, though he retained a part-time advisership with a room and secretary at No. 10.

His absence was to cost her dear when reflation began. In 1979, the incoming government had inherited Denis Healey's IMF-prompted Keynesian squeeze, which (1, it continued with changed rhetoric, in- creased determination and greater rigour.

As Keith Joseph had warned in 1976, in `Monetarism is not Enough', at that time taken to be Thatcherite economic doctrine, unless the state's take of real resources is reduced, all that monetary policy can do is limit the damage, choosing between a recessionary squeeze and inflationary re- laxation. The Government has not suc- ceeded in reducing the state's take of resources, either absolutely or relatively, so its monetary policy has remained on the knife-edge.

This expressed itself in the cold recep- tion given Nigel Lawson at the 1984 Conservative Conference, when he ex- plained with impeccable logic why reflation was out of the question. Since the desire to be loved is a deformation professionelle of Chancellors, Nigel Lawson chose relaxa- tion. As early as October 1985, Tim Congdon blew the whistle on him in Messel's Weekly Economic Monitor. In his Mansion House speech, the Chancellor had defended himself from accusations of monetary mismanagement on the grounds that 'the inflation rate is the jury and judge'. Congdon responded that given the two-year-plus time-lag between monetary expansion and inflation, 1988/9 would be the occasion for the verdict. It was. By 1988, while Mr Lawson was still animad- verting against 'teenage scribblers', the Prime Minister told him that Alan Walters intended to spend much more time in Britain as her adviser. Mr Lawson warned her against this, a strange reversal of roles, when a minister vetoes the Prime Minister's choice of adviser.

This was tantamount to saying that the Prime Minister should not have recourse to independent economic advice or second opinions, and hence that she should not form an independent judgment on her Chancellor's performance, or the eco- nomy's. Thou shalt have no other adviser but me. Even had all been well with the economy, Mr Lawson's threat would have been untoward. As things were, Mrs Thatcher's need for independent economic advice had never been greater.

At all events, the orchestrated witch- hunt against Alan Walters followed. This time, he did not really need my warnings. But someone had evidently been going with a fine toothcomb through everything he had written or said since returning to the States. five years previously. The embellished results were fed to lobby and economic journalists, with an appeal from prejudice to prejudice and an admixture of anti-Thatcherism, anti-intellectualism and even xenophobia, on the grounds that Sir Alan had lived several years in the USA. One two-year-old article which stated that Mrs Thatcher had concurred with Walters's view of the EMS, which was common knowledge, had to be eked out by allegat- ions that Sir Alan was speaking his mind in unspecified quarters and at City lunches.

For a man as extrovert as Sir Alan and with as strong convictions, his self-denying ordinances were commendable. But they did not help. He had been cast in the role of whipping-boy, and the lynch-mob was in no mood for reason. It was not difficult for the witch-hunters to allege that Sir Alan considered that you cannot control both money supply and exchange rate, since every first-year economics student knows that; the question was surely why Nigel Lawson and his Treasury prompters did not. Mr Lawson would have known that Mrs Thatcher could not conceivably throw Alan to the wolves without devaluing herself, since any adviser would have echoed Sir Alan.

I can only assume that Mr Lawson's ultimatum — Alan or me — was given in the knowledge that it would be rejected. This suggests that he intended to resign before the autumn statement, which bids to be depressing. He needed only a casus he'll which would appeal to the Prime Minister's enemies (in her own party) and opponents (in the other parties) more plausible than a defence of the Chancel- lor's actual record after what they had been saying about his policies over the past two years. How to make political capital is what politicians understand best about economics.

Sir Alan might console himself, as I did, with the thought that Aristotle's stint as adviser at the court of King Phillip of Macedon went even worse. He was lucky to leave with a whole skin, and was then exiled from Athens for his alleged Macedo- nian connexions. These are among the hazards of advertising.

Previous page

Previous page