Russia's greatest poet proses

Andrei Navrozov

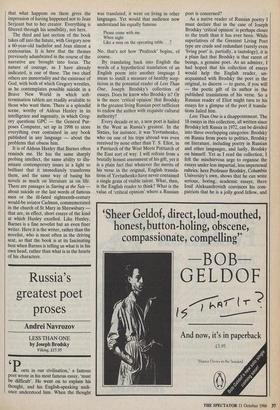

LESS THAN ONE by Joseph Brodsky

Viking, 115.95

Poets in our civilisation,' a famous poet wrote in his most famous essay, 'must be difficult'. He went on to explain his thought, and his English-speaking audi- ence understood him. When the thought was translated, it went on living in other languages. Yet would that audience now understand his equally famous

Please come with me When night Like a man on the operating table.. .?

No, that's not how Prufrock' begins, of course.

By translating back into English the words of a hypothetical translation of an English poem into another language I mean to instill a measure of healthy scep- ticism in the potential reader of Less Than One, Joseph Brodsky's collection of essays. Does he know who Brodsky is? Or is the mere 'critical opinion' that Brodsky is the greatest living Russian poet sufficient to endow the author with requisite cultural authority?

Every decade or so, a new poet is hailed in the West as Russia's greatest. In the Sixties, for instance, it was Yevtushenko, who on one of his trips abroad was even received by none other than T. S. Eliot, in a Patriarch of the West Meets Patriarch of the East sort of way. I will refrain from a brutally honest assessment of his gift, yet it is a plain fact that whatever the merits of his verse in the original, English transla- tions of Yevtushenko have never contained a single grain of visible talent. What, then, is the English reader to think? What is the value of 'critical opinion' where a Russian poet is concerned?

As a native reader of Russian poetry I must declare that in the case of Joseph Brodsky 'critical opinion' is perhaps closer to the truth than it has ever been. While superlatives of the Greatest Living Poet type are crude and redundant (surely even `living poet' is, partially, a tautology), it is a plain fact that Brodsky is that rarest of beings, a genuine poet. As an admirer, I had hoped that his collection of essays would help the English reader, un- acquainted with Brodsky the poet in the original, to discern — to guess, if you will — the poetic gift of its author in the published translations of his verse. So a Russian reader of Eliot might turn to his essays for a glimpse of the poet if transla- tions failed him.

Less Than One is a disappointment. The 18 essays in this collection, all written since Brodsky left Russia in 1972, can be divided into three overlapping categories: Brodsky on Russia from poets to politics, Brodsky on literature, including poetry in Russian and other languages, and lastly, Brodsky on himself. Yet as I read the collection, I felt the mischievous urge to organise the essays under less impartial, less impersonal rubrics: here Professor Brodsky, Columbia University's own, shows that he can write serious, boring, academic essays, there losif Aleksandrovich convinces his com- patriots that he is a jolly good fellow, and here Joseph Brodsky intimates to the Nobel Committee that he has waited long enough. Viewed another way, the book is a stuffy compilation of random notes, ideas, and facts that feeds on Brodsky's name as a poet rather than helps to establish it, as might have been hoped, in the English reader's mind.

There are few original thoughts in this book, although every page abounds in bald assertions, all the more arbitrary in the created intellectual vacuum. Why, for inst- ance, is 'attempting to recall the past' (in the opening sentence of the book's title essay) 'like trying to grasp the meaning of existence'? Is the pronouncement that 'ev- ery work of art' is 'a self-portrait of its author' (in 'On "September 1, 1939" by W. H. Auden') anything more than a sopho- moric cliche? And furthermore is it really true that (in 'On Tyranny') 'an individual perishes not so much by the sword as by the penis'?

One of the most conspicuous features of Joseph Brodsky's poetry is its subtlety. The originality and precision with which his gift transforms the banalities of everyday speech into revelations of tone and nuance are the hallmarks of the Brodsky poem. What went wrong? How can a man with even a decent ear for language describe a poet in his childhood as 'a little Jewish boy with a heart full of Russian iambic penta- meters'? And can a man with any brains at all suggest that it is

a thankless task for the imagination to think of the possible result of the 'one man, one vote' system in, for example, the one-billion- strong China: what kind of a parliament that could produce, and how many tens of mil- lians would constitute a minority there.

Yet these examples are typical of the quality of Brodsky's thought in Less Than One as its author speaks his mind on such subjects as history or politics. Worse still, when he tackles subjects essential to his sphere of comprehension, such as Russian literature (in 'Catastrophes in the Air,' for instance), bald assertions and hoary cliches give way to incomprehensible, ponderous, `academic' gibberish.

Given the magnitude of the historical night- mare he describes, this inability in itself is spectacular enough to suspect a dependence between aesthetic conservatism and resist- ance to the notion of man being radically bad. Quite apart from the stylistic consequ- ence for one's writing, the refusal to accept this notion is pregnant with the recurrence of this nightmare in broad daylight — anytime.

What went wrong? As with any cultural fiasco, no answer to this question is ex- pected, although in the case of Less Than One the sheer magnitude of the author's failures and of the reader's disappointment seems to invite speculation. 'It took me a while to understand that here one is permitted to speak in platitudes,' was a witticism attributed to Brodsky in Russian emigre circles in New York shortly after his arrival there. The remark was the talk of the town, and had Less Than One con- tained just one such mot it would have been worth the cover price. As it is, it appears that Brodsky has chosen to live by that witticism. In America, this is called `making a career.'

Andrew Navrozov, who emigrated from Russia to the US in 1972, was Editor of the `Yale Literary Magazine' from 1978 to 1986.

Previous page

Previous page