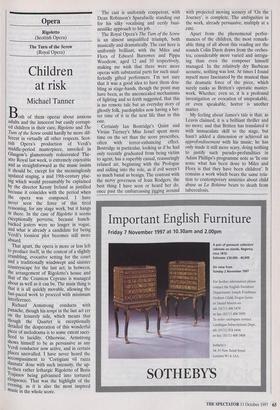

Opera

Rigoletto (Scottish Opera)

Children at risk

Michael Tanner

Both of them operas about anxious adults and the innocent but easily corrupt- ed children in their care, Rigoletto and The Turn of the Screw could hardly be more dif- ferent in virtually all other respects. Scot- tish Opera's production of Verdi's middle-period masterpiece, unveiled in Glasgow's glamorously redecorated The- atre Royal last week, is extremely enjoyable and as straightforward as the music insists It should be, except for the meaninglessly Updated staging, a mid 19th-century plac- ing which would presumably be explained by the director Kenny Ireland as justified because it coincides with the period when the opera was composed. I have never seen the force of this tired reasoning, for any stage work, but it hangs III there. In the case of Rigoletto it seems exceptionally perverse, because hunch- backed jesters were no longer in vogue, and what is already a candidate for being Verdi's looniest plot becomes still more absurd.

That apart, the opera is more or less left to produce itself, in the context of a slightly crumbling, evocative setting for the court and a traditionally windswept and sinister countryscape for the last act; in between, the arrangement of Rigoletto's house and that of the Countess Ceprano is managed about as well as it can be. The main thing is that it is all quickly movable, allowing the fast-paced work to proceed with minimum interference.

Richard Armstrong conducts with Panache, though his tempi in the last act err on the leisurely side, which means that though the Quartet is exceptionally detailed the desperation of this wonderful Piece of melodrama is to some extent sacri- ficed to lucidity. Otherwise, Armstrong Shows himself to be as persuasive as any Verdi conductor now active, and in certain Places unrivalled. I have never heard the accompaniment to 'Cortigiani vil razza dannata' done with such intensity, the up- to-then rather lethargic Rigoletto of Boris Trajanov being galvanised into tortured eloquence. That was the highlight of the evening, as it is also the most inspired Music in the whole score. The cast is uniformly competent, with Dean Robinson's Sparafucile standing out for his silky vocalising and eerily busi- nesslike approach to his job.

The Royal Opera's The Turn of the Screw is an almost unqualified triumph, both musically and dramatically. The cast here is uniformly brilliant, with the Miles and Flora of Edward Burrowes and Pippa Woodrow, aged 12 and 10 respectively, making me wish that there were more operas with substantial parts for such unaf- fectedly gifted performers. I'm not sure that it was a good idea to have them dou- bling as stage-hands, though the point may have been, as the unconcealed mechanisms of lighting and so forth suggested, that this is no remote tale but an everyday story of ghostly folk, paedophiles now having a bet- ter time of it in the next life than in this one.

Certainly Ian Bostridge's Quint and Vivian Tierney's Miss Jessel spent more time on the set than the score prescribes, often with terror-enhancing effect. Bostridge in particular, looking as if he had only recently graduated from being victim to agent, has a superbly casual, reassuringly relaxed air, beginning with the Prologue and sidling into the role, as if evil weren't so much banal as benign. The contrast with the nervy governess of Joan Rodgers, the best thing I have seen or heard her do, once past the embarrassing jigging around with projected moving scenery of 'On the Journey', is complete. The ambiguities in the work, already persuasive, multiply at a sate.

Apart from the phenomenal perfor- mances of the children, the most remark- able thing of all about this reading are the sounds Colin Davis draws from the orches- tra, considerably more varied and intrigu- ing than even the composer himself managed. In the relatively dry Barbican acoustic, nothing was lost. At times I found myself more fascinated by the musical than the dramatic force of the piece, which surely ranks as Britten's operatic master- work. Whether, even so, it is a profound investigation or evocation of unspeakable, or even speakable, horror is another matter.

My feeling about James's tale is that, as Leavis claimed, it is a brilliant thriller and no more; and that Britten has translated it with immaculate skill to the stage, but hasn't added a dimension or achieved an approfondissement with his music; he has only made it still more scary, doing nothing to justify such pseudo-profundities in Adam Phillips's programme note as 'In one sense what has been done to Miles and Flora is that they have been children'. It remains a work which bears the same rela- tion to contemporary anxieties about child abuse as La Boheme bears to death from tuberculosis.

Previous page

Previous page