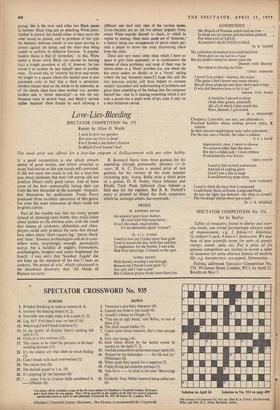

Chess

By PHILIDOR No. 97. J. HARTONG (`Jaarbook,' 1952)

BLACK (5 men)'

WHITE (6 men)

WHITE to play and mate in two moves: solution next week. Solution to last week's problem by Lipton: B-R 5, no threat. 1 . . . B x Kt (K 5); 2 R-B 5. 1 ...B x Kt (B 3); 2 R-Q 7. 1 ...B x R; 2 B x B. 1 . . . B-K 3; 2 Q x B. The point of thlt elegant problem lies in the 'tries' B-Kt 6, B-Q 6 and B-K 5, all.of which seem to produce much the same effect as the actual key B-R 5: it is worth examining them to see just why these alternative bishop .moves fail.

PROBLEM TERMINOLOGY

In this article I shall give a very brief description of some common problem themes and elements in themes and of the terms associated with them: I shall try to avoid again going over the ground covered by the last two 'articles and will assume terms explained in these to be understood.

Many themes are geometrical and one of the com- monest ideas is that of interference'—for example, White's key move being such that the various Black defences result in his pieces interfering with each other's lines of action; a popular special case of this is the `Grimshaw,' where two Black pieces (normally R and B) interfere with each other in turn on the same square —and a subdivision of this is the 'Nowotny,' where White as his key plays to the square of intersection of R and B so that whichever captures blocks the other. Another interesting special case is where the inter- ference results in unpinning a White piece, and many problems have been composed on this theme.

'Half-pins' are another ingredient in problem com-

posing; this is the term used when two Black pieces lie between Black king and an attacking White piece. Neither is pinned. but should either of them move the other would be pinned, and in problems of this type the thematic defences consist in one piece moving to protect against the threat, and the other then being unable to perform its defensive function. A popular modern theme is that of 'correction.' In this, White makes a threat which Black can obviate by moving (say) a knight anywhere at all; if, however, he just moves it at random he lays himself open to another mate. To avoid this, he 'corrects' his error and moves the knight to a square where this second mate is also prevented-only to find that a third is permitted. Modern themes tend on the whole to be elaborate, as all the simple ideas have been worked out; another mod'ern idea is 'threat separation'-in this the key threatens mate in several ways, and Black's various replies 'separate' these threats by each allowing a different one (and only one) of the various mates. Cross-checkers are, an old but always popular form, where White exposes himself to check, to which he replies by mating: these make great use of 'batteries,' a battery being any arrangement of pieces which per- mits a player to move one away discovering check from the other.

These and very many other ideas which I have no space to give form separately or in combination the themes of chess problems, and most of them may be shown either in a 'block' problem (i.e. one where the key move makes no threat) or in a 'threat' setting (where the key threatens mate).] I hope this and the two previous articles will have helped to increase readers' enjoyment and understanding of problems and given them something of the feeling that the composer himself has-that he is making something which is not only a puzzle but a small work of art, even if only on a very miniature canvas.

Previous page

Previous page