CITY DIARY

CHRISTOPHER FILDES

One of the Greek colonels' sillier mistakes was to fall out with M Xenophon Zolotas. When last year he resigned the governorship of the Bank of Greece, finding himself unable to work with the junta, he must have been the world's most senior central banker. Inter- nationally respected as a tough—even irascible —monetary liberal, M Zolotas saw earlier than most how necessary it would be to allow the world's monetary resources to increase with the growth of trade.

I was delighted to see that resignation has taken none of the edge off M Zolotas's re- forming zeal. His latest proposal—for a gold certificate, guaranteed for whatever dollar-gold rate may prevail, into which (rather than into gold) official dollar balances could be con- verted—is strongly argued. The gold pool, hq says, was a disaster, guaranteeing speculators against loss by assuring them that they. would never have to sell gold below $35: 'All that' Goldfinger would need to succeed would be an identity card certifying hi, capacity as avowed gold speculator.'

Liberals, monetary or otherwise, are not happily placed in Athens. But M Zolotas is made of sterner stuff. He was governor-in- exile of his bank during the German occupation of Greece. And, as though foreseeing an ad- ministration with the habit of parking people it dislikes on off-shore islands, he has for many years kept in training as an accomplished long-distance swimmer.

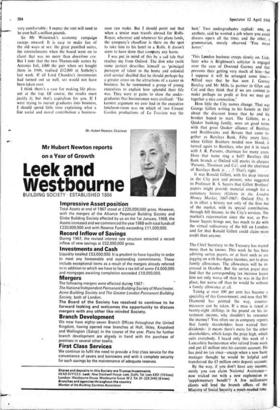

Brown paper is tied across the AEI nameplates on that vast headquarters overlooking the Green Park; and now the 'To let' signs will be going up. For the chairman who is feeling cramped, this is quite an opportunity. It runs to six floors, two basements and a car park— almost 200,000 square feet in all—and is really ,

very comfortable: I expect the rent will need to be over half a million pounds.

So Mr Weinstock's economy campaign sweeps onward. It is easy to make fun of the old ways at AEi: the great panelled suites, the retrenchments when the board went on to claret that was no more than deuxieme cru. But I note that the two Thames-side scenes by Antonio loll, £400 the pair when AEI bought ,them in 1949, realised £12,000 at Sotheby's last week. If all Lord Chandos's investments had turned out so well, AEI would not have been taken over.

I think there's a case for making life pleas- ant at the top. Of course, the results must justify it; but that's capitalism for you. If I were trying to recruit graduates into business, I should spend little time explaining what a fine social and moral contribution a business-

man can make. But I should point out that when a Senior man travels abroad for Rolls- Royce, wherever and whenever his plane lands, the company's chauffeur is there on the spot to take him to his hotel in a Rolls. It doesn't seem to have done that company any harm.

I was put in mind of this by a sad tale that reaches me from Oxford. The don who (with some justice) describes himself as 'principal purveyor of talent to the home and colonial civil service' decided that he should perhaps-fay a greater stress on the attractions of a career in business. So he summoned a group of young executives to explain how splendid their life was. They were at pains to 'show the under- graduates that businessmen were civilised : 'The keenest argument we ever had in the executive luncheon-room was on which of two Covent Garden productions of La Traviata was the best.' Two undergraduates replied: one, an aesthete, said he wanted a job where you could discuss opera all the time; and the other, a • grammarian, merely observed 'You mean better.'

`This London business creeps slowly on. Link- later who is Brightwen's solicitor is engaged over the case of Overend Gurney and that prevents their getting very much of him_ —,but I suppose it will be arranged some time— Alfred says that he has seen J. Gurney Barclay and Mr Mills (a partner in Glyn and Co) and they think that if we are content M make 'perhaps no profit at first we may get together a nice connection.'

How little the City names change. That was George Gillett writing to his fiancée in 1867 about the discount house that he and his brother hoped to start. The Gilletts, as a Quaker banking family, were on good terms with that great Quaker alliance of Barclays and Braithwaites and Bevans that came to- gether as Barclays Bank. Fifty years later, when Gillett Brothers needed new blood, it turned again to Barclays, who put it in touch with J. R. Parsons, chairman for many years. Does that name ring a bell? Barclays Old Bank branch at Oxford still marks its cheques 'Parsons, Thomson and Co'; and the chairman of Barclays Bank is . . .? That's right.

It was Ronald Gillett, with his deep interest in the City past and present, who suggested to Professor R. S. Sayers that Gillett Brothers' papers might provide material enough for .a centenary history (Gilletts in the London Money Market, 1867-1967: Oxford 35s):• It is in effect a history not only of the firm but of the market, with its special contribution, through bill finance, to the City's services. The market's rejuvenation since the war, as Pro- fessor Sayers brings out, has much to do with the virtual rediscovery of the bill on London; and for that Ronald Gillett could claim -more credit than anyone.

The Chief Secretary to the Treasury has started more than he knows. This week he has been advising surtax payers, or at least such as .are jogging on with five-figure incomes, not to draw family allowances. The allowances will be in-

creased October. But the surtax payer may find that the corresponding tax increase leaves him not only worse off than he was in the first place, but worse off than he would be without a family allowance at all.

Taxing at over 100 per cent has become a speciality of this Government; and now that Mr Diamond has pointed the way, counter- measures can be taken. If a man is taxed at twenty-eight shillings in the pound on his in- vestment income, why shouldn't he renounce the income? You often see in company reports that family shareholders have waived their dividends: it means there's more for the other shareholders, which keeps the price high, which suits everybody. I heard only this week of a Lancashire businessman who retired from work and put £3 million into his current account. He has paid no tax since—except when a new bank manager thought he would be helpful and transferred the £3 million onto depOsit account.

By the way, if you don't have any income, surely you can claim National Assistance— now tricked out with a new euphetnism as 'supplementary benefit'? A few millionaire clients will lend the branch offices of the Ministry of Social Security a much-needed- tone.

Previous page

Previous page