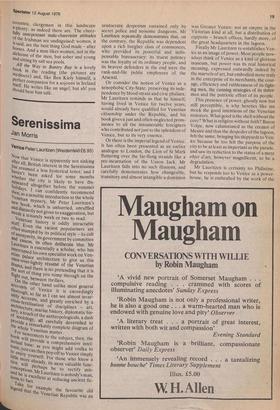

Storyteller

Mary Kenny

All the Way to Bantry Bay Benedict Kiely (Gollancz E6.50) As the three people who understood the Schleswig-Holstein question ,realised, a border is an arbitrary business: there are German-speaking Danes on one side, and Danish-speaking Germans on the other. It is not the frontier line, with its passports and customs sheds that makes the difference between nations it is the culture: the way people talk and think, the way they eat and drink, the stories they tell each other, the songs they sing, the God they worship, the way they marry and bring up their families. This is also true of Ireland, which is divided by a border. The people of the North of Ireland are different from the people of the Scluth of Ireland (and have been since ancient times: the affair of 1690 is nothing new), but where are the differences to be drawn? A frontier carved for political expediency, or even compromise, is culturally absurd.

If you want to know about a country and a Spectator 12 August 1978 people, don't go to a political economist ora civil servant: ask a scholar. Ask a man who has travelled every road and by-waY 0f a country on foot, stopping at every town, talking at local hostelries, sitting for tea in people, s houses, going to old graveyards browsing among old bookshops this is the man who knows about a country's heart and the true geography of its soul. Benedict Kiely, an Ulster scholar, novelist, storyteller, talker, walker, bard, is such a Man: he knows Ireland from the stones up. And in his book about his travels around the island,A" the Way to Bantry Bay, something of the true nature of the border country in Ireland emerges, something which would never be perceived by the Sunday Times insight team if it researched for a thousand years' for that knowledge lies in the very seedbed o. f the mystical landscape and in the Intimate knowledge of the physical land, too. Kiely himself was born in Co. Tyrone, wwhhaicthisispooflictiocualrlsey Noonertohef rtnheIrseixlacnodr yteief ts the culture of his home base would probably be classified by an anthropologist as the Tyrone-Monaghan culture although Monaghan is, properly, in the RePubbe; (Just as Donegal is the proper hinterland Of Derry city, and from the folklore and the children's stories told in Donegal, Ycitt can tell that the county is characteristicallYf Ulsteronian: fierce, religious, pagan, full ° great giants in pain, heroes with golden tresses, glorious battles. When Fiona Mac" Cumhaill an ancient Ulster hero was rewarded by the gods with three hundred years residence in a faery land called Tir ua, nog, he whiled it away enjoying eternal youth libations, and glorious battles.) In famous, notorious Crossmaglen, toe,. known today for its bitter killings, part ot the 'murder triangle' of South Armagh, Pen Kiely looks through the eyes of its ancient. traditions. Crossmaglen where, mci dentally, until thirty years ago the Iris" language could be heard as a native tong!!! has been known for its fierceness and it banditry since the sixteenth century. Oh, the wild, wild men from Crossmaglen put wh! kyoeyutintimwheotawy.e. nthtetobathlleadbaodf.the down 11 11 W , But Ben Kiely walks all over Irelan • that men a great ear for the kind of anecdote !oho': chl• men love to tell each other over a Oat' here, it is told with the skill of the seanna fall ot a (In its lesser manifestation, it is thteeshbaaggrey dog story.) How Dan Donnelly h knuckle boxer, on whom a fine lady olfe gambled her estate, ended his days in dignified poverty, and he with the arms so that he could scratch the back of his kn.f without bending. How Monsignrn or paaaa__,Y, Browne, a man of pure matheatics nu Middle Irish, a man who had translated Dante into the Gaelic, talked rings around Jean-Paul Sartre in John Houston's house'', Galway; and how Sartre fled back to the next day every after being told that aetvii.of second priest in Ireland was a poi Yrn the same standing. There are mad lords and eccentric clergymen in this landscape a-Plenty: as indeed there are. The cheerfully unrepentant male-chauvinist attitudes of the Irishman are undisguised: women, it is said, are the best thing God made — after horses. And a man likes women, not in the alehouse of the men, but sober and young and sitting by salt sea pools. All the Way to Bantry Bay is a lovely book in the reading (the pictures are mediocre) and, like Ben Kiely himself, a Perfect companion for a sojourn in Ireland itself. He writes like an angel, but ah! you Should hear him talk.

Previous page

Previous page