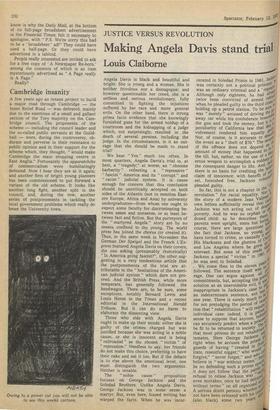

JUSTICE VERSUS REVOLUTION

Making Angela Davis stand trial

Louis Claiborne

Angela Davis is black and beautiful and bright. She is young and a woman. She is neither frivolous nor a demagogue: and however questionable her creed, she is a selfless and serious revolutionary, fully committed to fighting the injustices suffered by her race and more general evils. On the other hand, there is strong prima facie evidence that she knowingly furnished guns for the armed holdup of a courtroom and the kidnapping of a judge which, not surprisingly, resulted in the death of several persons, including the judge. In the circumstances, is it an outrage that she should be made to stand trial?

We hear " Yes " much too often. In most quarters, Angela Davis's trial is, at best, a "tragedy;" at worse, an "obscene barbarity" reflecting a " repressive " " fascist" America and its " corrupt " and "racist " judicial system. It is cause enough for concern that this conclusion should be uncritically accepted on both sides of the Atlantic (not to mention Eastern Europe, Africa and Asia) by university undergraduates—from whom one ought to expect some faculty for discriminating between sense and nonsense, or at least between fact and fiction. But the purveyors of the "martyred Angela" story are by no means confined to the young. The world press has joined the chorus (or created it). Thus, in the same week in November the German Der Speigel and the French L'Express featured Angela Davis on their covers, the one asking (presumably rhetorically) "Is America going fascist?", the other suggesting in a very tendentious article that the postponements of the trial are attributable to the "hesitations of the American judicial system" which dare not proceed. And the British Press, while more temperate, has generally followed the bandwagon. There are, to be sure, some exceptions, notably Bernard Levin and Louis Heren in the Times and a recent editorial in the Internationa/ Herald Tribune. But it can do no harm to elaborate the dissenting view.

Those who side with Angela Davis ought to make up their minds: either she is guilty of the crimes charged but was justified because she was acting in a noble cause, or she is innocent and is being " railroaded as the chosen " victim " of "repression." Needless to say, her friends do not make this choice, preferring to have their cake and eat it too. But if the debate is to rise above the emotional level, one must distinguish the two arguments. Neither is tenable.

The "noble cause" proposition focuses on George Jackson and the Soledad Brothers. Unlike Angela Davis, George Jackson was in some sense a martyr. But, even here, biased writing has warped the facts. When he was incar cerated in Soledad Prison in 1961, Jac was certainly not a political prisonerter was an ordinary criminal and a ' rePearid Although only eighteen, he had alhreber twice been convicted of armed W'ec. when he pleaded guilty to the third c1'1171 holding up a petrol station. To be stireg't,/, was " merely " accused of driving th.,e.0 away car while his confederate brana.I the gun and took the money, but it .1:ic peculiarity of California law that volvement rendered him equallY Ocrit, Nor, of course, is it accurate to de‘,se the event as a "theft of $70." The se' ty of the offence does not depend le amount of money that happened W the till, but, rather, on the use of a 3# erous weapon to accomplish a rob:131)101i the consequent danger to life. Ancl,„lote" there is no basis for crediting the u"eout claim of innocence: with benefit of t sel, furnished free, Jackson v°1tin pleaded guilty.

So far, this is not a chapter ,n is revolution" for racial equality. r: the story of a modern Jean Valjead'e4 own letters sufficiently reveal that „eri' Jackson was not acting out of de'"AV poverty. And he was no orphan Oro r doned child: as he describes th parents were upright, stern but lov course, there are large questions shoo' the fact that Jackson, so young; seerf'. have turned to crime, so casuallY His blackness and the ghettos of and Los Angeles where he greW ceoP relevant. But none of this madLt, Jackson a special " victim " in 1" he was sent to Soledad. ea We come then to the eleven Y followed, The sentence itself '05,1 pf!', rage. One can argue against a`,001 commitments, but, accepting the Pvii;5! solution as an unavoidable evil, ito inappropriate in Jackson's case two an indeterminate sentence, not bri one year. There is surely much Woof for not prejudging the period of 100! tion that " rehabilitation " will reqtuerit individual case: indeed, it is Pap sense to suppose that anyone, b,esoliel, can accurately predict when a 101,011",:, be fit to be returned to societY.,1.tate. that most prisons do not rehab,'l inmates, Here George Jacks? right when he accuses the Pris°,101fL guards of having "created in irate, resentful nigger," who W0110 cs0 forgive," "never forget," and 0:,11,0elei believe in "war without terms: 5tell"; be no defending such a prison sYie it does not follow that the Par°oci5,Y , refusal to relase Jackson was ged even mistaken, once he had dele atItY. 1 without terms " on all organised tie A serious doubt persists whether„or , not have been released with his cue, (also black) some two years Crime. But, wherever the fault lies, there may Well have come a point of no return, even before Jackson and the other two Soledad Brothers were charged with murdering a guard. It ought not to be so difficult both to understand the honest hesitation of the parole authorities, and to understand how frustrations, provocations and violence produced such an eloquent and angry man. It is right to condemn the racism and sadism that pervade too many American Prisons. But one must also denounce the retaliatory savagery in which four prison F,uards and two " enemy " inmates were executed " at Soledad in 1970 and last sunlit-ler at San Quentin. If, as charged, these crimes are properly attributed to hero, Jackson, he is no unblemished 'Jere, even in death. Nor are they " noble " Who sought to avenge him by holding a ?lin at an innocent judge who had no part In Jackson's sentence, his continued incarceration, or his treatment in prison' But even if this were a fine "revolutionary act," i' 1:),NY can those responsible justify shouting 'I=411" when they are caught and brought ? account? Surely, the courts, too, have a rIght of self-defence. A All this, to be sure, is beside the point if Sinc.agela Davis is innocent. Rather a shame, e she is then no longer the revolutionary heroine who joined in the rhash attempt to rescue her loved one. And r.,er case loses the poignant appeal of ,feor..,e b Jack son's ordeal. Well . . . anyhow, 'Ile_is being "railroaded rsserhe accusations laid against her " op ,,gueors " are already too many to cata, and there is no reason to suppose irle list has ended. fat us look at some of them against the yo,S' On August 7, 1970, George Jackson's co"ong brother Jonathan entered the Cal' tflotY Courthouse in San Rafael, to 1,1,-rnia, drew a gun, distributed others gunu'ack prisoners there, and together at • Point they kidnapped the presiding ladge th jurel's, e prosecutor and three women , all With fore„ th the announced purpose of /11 the the release of the Soledad Brothers. soo,!,subsequent shoot-out the judge, kilieg.,In. an and two of his confederates were ten4 Presumably no one seriously con1,vhich that this was not an incident for brogut u, those responsible ought to be WaT's to book. The only one of the kidWho survived is Ruchell Magee, know7e,s, been duly charged. So far as we Angeia`11.re only other person implicated Is ?Wrier 0;-)avls, said to be the registered the co three or four of the guns used in gestionurtroorn holdup. There is no suga sour that anyone else was involved, as ItIlltich focre thoef ,,vv:inagploinnsg or otherwise. So ,, tit lx, out" argument. dregge-,,ms not Angela Davis unfairly Drose, into " the courthouse holdup that '"uon? partesrnggesti is difficult to appreciate el:, She was a very vocal sup b(4 of Geo ,efit th,,,, kidnapping Jackson, for whose .efrierid tounapping was done; she had Whom „eLd his brother Jonathan, with cola , one was 1.41°11se allegedly seen near the 1.41°11se used t ‘ve are t..., .la he day before the affray; and l,ve.`" several (if not all) of the guns °aIY re hers, one having been purchased ellcIngli 30 daYs earlier. This may not be convict her, but, in any court, in any land, it justifies the charge that she was involved and warrants a trial (at which other evidence against her, or exonerating her, may well come forth). And so, all the arguments over the composition of the grand jury which indicted her are largely wide of the mark.

Some of her sympathisers acknowledge that, perhaps, there is a case for putting Angela Davis to trial, but they inveigh against the nature of the charges: murder, aggravated kidnapping, and conspiracy to commit those crimes. After all, at worst, she only supplied the guns. Legally, there is nothing unusual here. If Angela Davis procured the weapons for Jonathan Jackson so that he would use them as he did, she is as guilty as he under the law of any Anglo-Saxon jurisdiction. And, morally, as the older and presumably more influential partner, she is the more guilty — not to mention the special guilt of sending the " man-child " to his death while she remained safely in the background. Nor is the murder charge a mystery: California. like many other jurisdictions, applies the so-called felony-murder doctrine under which the perpetrator of a violent felony (such as armed kidnapping) is held responsible for any death which directly results. The rule is debatable, but it is neither unusual nor put to a strained use in this case.

Next we must face the claim that the trial ought to be held in a federal court, rather than a California State court, or if a California court, in San Francisco instead of San Rafael or San Jose. Surprisingly, there is a provision in American law for prosecution of a State criminal case in a federal court. But, stretching that exceptional rule to its outer limits, it applies only when the defence is that the act charged was authorised by some federal law assuring equality of rights as between the races, or when it is demonstrable that the State courts will refuge to respect some procedural right which federal law confers on the defendant. Since armed kidnapping and murder are condoned by no federal equal rights law and there is no basis for concluding that Angela Davis will be denied her rights in the courts of California, she does not meet the test and must be tried in the normal way, before a tribunal of the sovereignty whose laws she is accused of breaking. No conceivable discrimination here.

The question which California court should hear the case is perhaps more debatable. Usually, of course, one is tried where the offence occurred, and that regardless whether the local inhabitants from whom a jury will be chosen are deemed simpatico or not. Yet there are cases for a change of venue and this was probably one of them — on the ground that the very courthouse where the crime occurred, and the local judge was killed, is not the most neutral forum. That objection has now been met by transferring the trial to San Jose, further away from the scene than the defendant wished. The present demand for another transfer to San Francisco because more blacks, more poor and more radicals live there is not legally sound. No one is entitled to be judged only by those who share his colour or class or creed. It would be a mockery if black revolutionaries were tried by black revolutionaries and Klansmen by Klansmen. Nevertheless, for the sake of appearances (which is to say, as a matter of judicial politics), it might be best if Angela Davis got her way and the trial were removed to San Francisco or another California locality with a less all-white middle class population. Justice will be done in any case, but it is always well if it is "manifestly seen to be done."

What else? Ah, yes, the denial of bail. The short answer is that the almost universal practice is to deny bail in a capital case, which this is. Any inclination to do the extraordinary and release Angela Davis pending trial is foreclosed by her actions as a fugitive for more than two months, during which she apparently sought (however ineptly) to reach Cuba whence extradition is impossible. It is true that incarceration often inhibits the defendant's ability to help in the preparation of the defence and it is regrettable that the risk of flight — and consequent defeat of justice — sometimes requires such a result. But this is hardly a compelling instance: rarely has a defendant had so much legal and extra-legal help in preparing her case. Keep your tears for the anonymous poor, black and white, who still too often languish in jail, unknown and unrepresented.

Speaking of "languishing in jail," why has the State of California delayed the start of the trial of Angela Davis for more than fifteen months? That charge is perhaps the most irresponsible of all. For if anything is clear it is that Angela Davis and her former co-defendant Ruchell Magee (whose case is now severed), not the State, have caused the postponements. One cannot call to mind any case in which more preliminary motions have been tendered to the court, and not all at once, but at nicely spaced intervals.

Does the record reveal a judicial system (or two, one State, one Federal) bent on destroying Angela Davis? Repression, ty pically, is swift, not patient. No, it is the other way around. Every indication is that Angela Davis and her advisers, by abusing the process through belated and often frivolous claims, have sought to gain time and accumulate an impressive dossier of "denials." Why? Perhaps hoping to exhaust the prosecution and the court. More likely, to inflate the image of a "martyred Angela" held behind bars and to whip up public opinion behind the defendant. And, in the end, to bring down the judicial temple.

Previous page

Previous page