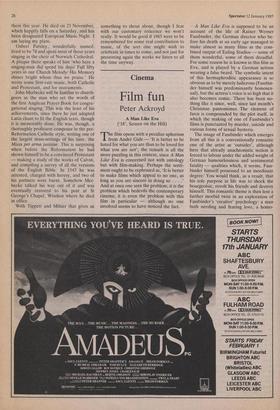

Cinema

Film fun

Peter Ackroyd

The film opens with a peculiar aphorism from Andre Gide — 'It is better to be hated for what you are than to be loved for what you are not'; the remark is all the more puzzling in this context, since A Man Like Eva is concerned not with ontology but with film-making. Perhaps the senti- ment ought to be rephrased as, 'It is better to make films which appeal to no one, as long as you are sincere in doing so . . . And at once one sees the problem; it is the problem which bedevils the contemporary cinema; it is even the problem with this film in particular — although no one involved seems to have noticed the fact. A Man Like Eva is supposed to be an account of the life of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the German director who be- fore his death at an early age managed to make almost as many films as the com- bined output of Ealing Studios — some of them wonderful, some of them dreadful. For some reason he is known in this film as Eva, and is played by a German actress wearing a false beard. The symbolic intent of this hermaphroditic appearance is so obvious as to be merely ludicrous (Fassbin- der himself was predominantly homosex- ual), but the actress's voice is so high that it also becomes comic. There has been no- thing like it since, well, since last month's Christmas pantomimes. The element of farce is compounded by the plot itself, in which the making of one of Fassbinder's films is punctuated by murder, suicide and various forms of sexual hysteria.

The image of Fassbinder which emerges from all this is a conventionally romantic one of the artist as 'outsider', although here that already anachronistic notion is forced to labour under the added weight of German humourlessness and sentimental fatality — qualities which, it seems, Fass- binder himself possessed to an inordinate degree! You would think, as a result, that his sole purpose in life was to shock the bourgeoisie, revolt his friends and destroy himself. This romantic theme is then lent a further morbid twist in an exploration of Fassbinder's 'creative' psychology: a man both needing and fearing love, a homo- , sexual who combines self-hatred with self- aggrandisement. These are in fact the ordinary pieces of cardboard which amateur psychologists use to construct the figure of the 'artist', and in the process all artists end up by resembling each other. So this film despite its pretensions, does not even get close to suggesting the unique and fatal compulsion which drove Fassbinder forward.

A Man Like Eva is at least intermittently interesting about the nature of film-making itself, although putative students of that art Will take one glance at this film before Changing course to dentistry or farming; if this account is to be trusted, everyone involved in the cinema not only goes through hell in front of the cameras but, more particularly, also behind them. There IS no one here who is not on the edge of hysteria or bankruptcy: the cast, for exam- ple, seem to spend more time engaged in various emotional crises with each other than they do in making the film. Now that sex has become uninteresting where it is not entirely irrelevant, this is an added burden for an audience who came for an exposé and get merely exposure.

But if no one in this film is terribly attractive, its subject is the least prepos- sessing of all: he spends most of his time smoking cigarettes, watching football on television, or wearing a little hat in the manner of Truman Capote. If A Man Like Eva is to be believed, Fassbinder was Clearly impossible to work with also, since he veered wildly from imperiousness to irresponsibility. 'My art is an art of power,' he admits at one point. 'Power over peo- ple. 'He says this while drunk and wearing a White veil in a provocative manner, but it is Still a moderately interesting account of the director's role: it is a pity someone did not make a film out of it.

In fact A Man Like Eva suggests that an entirely new form of cinematic biography is about to emerge — the film version of assassination, it is biography by debase- ment; Fassbinder emerges here as a malevolent dwarf whose incompetence would render him unfit to direct a televi- sion commercial and whose general un- pleasantness makes him a most unlikely candidate for the infatuation which

apparently he provoked. How much of it is true, how much false, and how much interpretation', one doesn't know and one doesn't care: this is a film which becomes SO irritating after half an hour that as a result it seems to go on for ever. And on the level that really matters — on the level Of that art which Fassbinder practised to some effect — it is a grotesque travesty. Fassbinder had, at the very least, a wonderful visual sense; this film is messy Where it is not just cluttered. Fassbinder

knew also how to pace and organise a narrative in an interesting fashion; this film ts scattered and opaque. It is altogether a charmless exercise in hysterical whimsy, Which reflects badly upon all concerned — even, in this case, the innocent, or at least Powerless, dead.

Previous page

Previous page