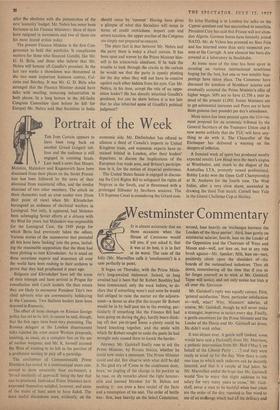

CRACKS IN THE KHADI CURTAIN

By VICTOR ANANT rl RACKS in Asia's second largest political monolith, the Indian National Congress which claims a primary membership of 8,000,000, have begun to appear at the same time as Mao Tse-tung has detected chinks in Chinese Communism. However, the two mutations are related only in their timing.

Mao is in full control of his chopsticks. He said, 'Never has our country been as united.

ŌĆó ŌĆó . However, this does not mean that there are n6 longer any contradictions in our society.' Mr. Nehru uses sloppy fingers. He said, 'So far as the elections are concerned there is no cause for despair or a sense of defeatism. . . . Something has to be done to hold the Congress together, some ideology.'

When Mr. Nehru is in Delhi it isŌĆó difficult to see the party wood for the Prime Minister. But with him in London the Congress that he drove to victory in the second general elections is clearly engaged in the task of defeating him. A hundred roses are blooming here today in a hundred khadi buttonholes.

The truth is the decline of the Congress, founded in 1885 entirely through the initiative of a Viceroy-blessed but Mill-and-Burke-inspired Briton, began in 1947. After the transfer of power, its specific purpose achieved, if has had no valid raison d'etre. Not even a leader of Mr. Nehru's glitter can be a substitute for a cohesive Community of interests. Congressmen must fulfil two fundamental conditions : they must be habitual wearers of khadi and teetotallers. In our times these conditions can hardly provide a party New Delhi with more than a temporary, theatrical integra- tion.

Till 1920, the year of Gandhi and his first non- cooperation call, the Congress remained true to its founder's original concept of `fifty men, good and true,' the elite, the most highly educated of the nation,' an articulate, enlightened but essentially loyalist, native safety-valve. Much to the alarm of the last British President of the Congress, the theosophical Mrs. Annie Besant, it was Gandhi who decided to inject mass- momentum into the organisation.

Unfortunately for the Congress it is not ad- mitted than Gandhi was essentially a politician and a saint only at second remove. It was politi- cal shrewdness that enabled him to seize upon the two basic virtues of the HinduŌĆörenunciation and an infinite capacity for physical suffering. In 1922, when Gandhi decided to accelerate the pace of nationalism thfough civil disobedience, he was in complete control of the forces he was setting looseŌĆömuch as Mao is now when he says that many schools of thought must contend. The moment he heard his followers had burned alive a sub-inspector of police and twenty-one police constables Gandhi suspended the agitation and called it a 'Himalayan mistake.' Again, in 1939, when Mr. Subhas Chandra Bose was swaying the younger elements of Congress towards extremism, Gandhi merci- lessly suppressed him. With political manoeuvring of the most unsaintly kind Gandhi collected enough votes to unseat Mr. Bose, who had been elected president. Mr. Nehru then sided with Gandhi, betraying his friendship with Mr. Bose. As it turned out Gandhi was justified : Mr. Bose collaborated with Axis forces to organise an Indian National Army to invade India.

In 1948, the year after Independence, it was again ŌĆó Gandhi who suggested that the Congress should be disbanded. For the majority of Con- gress leaders who saw in the party a ready-made, country-wide machinery for power moves, it was an uncomfortable decision to contemplate. They argued that in the interest of protection from Pakistan the Congress should retain its structure intact. Membership then was half what it is to- day. Congressmen themselves concede that at least a third of the present primary membership is `bogus'ŌĆö`members' whose four-anna subscrip- tion is paid up in thousand-rupee chunks by delegates who are directly 'elected' to the annual session. (In two weeks' time the highest, delibera- tive body of the party is meeting to alter the constitution to make elections indirect, and pyramidal, and make the village councils the base of the party.) Where has this led the party to? Younger Con- gressmen frankly admit that 'Nehru has been our greatest liability as he has been our greatest asset.' He is an asset as the only personality in India who can remain a live symbol of unity. He is a liability because of his own personal con- fusion. The gap between him and the party is the gap between his idealism, his basic goodness, and the realistic self-interest of the second rung of the Congress high command.

Ideologically Mr. Nehru has given the party two slogans for the future : secularism and Socialism. Both are the causes of present disintegration. In South India, non-Brahmin party members have broken away to form a separate 'anti-Brahmin' movement; in Bombay, Maharashtrian Congress- men and Gujerati Congressmen have split into two camps; in Punjab, the Sikhs who were asked to climb on to the election band-wagon, beards, daggers and all, are now being opposed by Hindu Congressmen; in Central India, the Scheduled Castes, disillusioned that Hindus will ever give them equal rights, are turning towards Buddhism and have even asked for a separate `Buddhistan.' That is the secular balance-sheet.

In the last three weeks Hindu business interests have begun to express fears about the extent of State control. So far while the Government has talked about Socialism,' top leaders of the party, includ- ing Mr. Nehru himself, have given private assurances to individual investors that their interests will be protected; this was pronounced during the elections, when large funds were neededŌĆöbut these assur- ances have lost their value after the elections with the presentation of the new 'austerity' budget. Mr. Nehru has never been fortunate in his Finance Ministers : three of them have resigned in succession and two of them are his most feared critics today.

The present Finance Minister is the first Con- gressman to hold this portfolio. It complicates matters for those who financed Gandhi, like Mr. G. D. Birla, and those who believe that Mr. Nehru will honour all Gandhi's promises. In the last two weeks a showdown was threatened in the two most important business centres, Cal- cutta and Bombay. It was Mr. G. D. Birla who arranged that the Finance Minister should have talks with snarling, menacing industrialists in both places. In a long lecture to the All-India Congress Committee Oust before he left for Europe) Mr. Nehru said that Socialism in India should come by 'consent.' Having been given a glimpse of what this Socialism will mean in terms of credit restrictions, import cuts and severe taxation, the upper reaches of the Congress are simply not prepared to consent.

The plain fact is that between Mr. Nehru and the party there is today a khadi curtain. It has been spun and woven by the Prime Minister him- self in his aristocratic aloofness. If he took the trouble to look thfough the cracks in the curtain he would see that the party is openly plotting for the day when they will not have to connive against each other hidden from his eyes. Can Mr. Nehru, in his time, accept the role of an oppo- sition leader? He has directly inherited Gandhi's goodness, but can he show before it is too late that he also inherited some of Gandhi's political judgment?

Previous page

Previous page