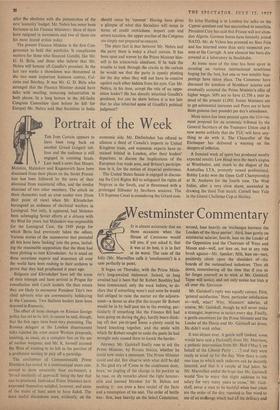

--Westminster Commentary

IT is almost axiomatic that on those occasions when the House of Commons would tell you, if you asked it, that it was at its best, it is in fact at its worst. The case of the lolly (Mr. Macmillan calls it 'emoluments') is a case perfectly in point.

It began on Thursday, with the Prime Minis- ter's long-awaited statement. Indeed, so long awaited had it been that Sir Robert Boothby had been constrained, only the week before, to de- clare that if something wasn't said soon he would feel obliged to raise the matter on the adjourn- ment—a threat so dire (for the temper Sir Robert would be in by half-past ten in the evening, par- ticularly if something like the Finance Bill had been going on during the day, hardly bears think- ing of) that pin-striped knees a-plenty could be heard knocking together, and the smile with which Sir Robert sought to undo the panic he had wrought only caused them to knock the harder.

Anyway, Mr. Gaitskell finally rose to ask the Prime Minister, by Private Notice, whether he could now make a statement. The Prime Minister could and did. But observe with what skill he did it. No glad cry of 'Come to the cookhouse door, boys,' no jingling of the change in his pockets as he rose, no sly remarks about the right honour- able and learned Member for St. Helens not needing it : not even a bare recital of the facts and a resumption of his seat. The order of battle was: first, lean heavily on the Select Committee; second, lean heavily on 'exchanges between the Leaders of the three parties'; third, lean gently on ministerial salaries; fourth, lean on the Leader of the Opposition and the Chairman of Ways and Means and—well, not lean on, but at any rate brush against—Mr. Speaker; fifth, lean on—nay, positively climb upon the shoulders of—the boards of the nationalised industries. Then sit down, remembering all the time that if you so far forget yourself as to wink at Mr. Gaitskell Taper will notice, and not only notice but blab it all over the Spectator.

Mr. Gaitskell's reply was equally correct. First, 'general satisfaction.' Next, particular satisfaction at—well, what? Why, Ministers' salaries, of course; Mr. Gaitskell, though he will never make a strategist, improves in tactics every day. Finally, a gentle encomium for the Prime Minister and the Leader of the House and Mr. Gaitskell sat down. He didn't wink either.

It was almost over. A gentle sniff (indeed, some would have said a Pecksniff) from Mr. Morrison, a pathetic intervention from Mr. Holt ('May I, on behalf of the Liberal Party . . .') and they were ready to wind up for the day. Now there is only one tune to which such cadavers can be decently interred, and that is a couple of bad jokes. So Mr. Macmillan added the hope that Mr. Gaitskell would 'live to enjoy this slight addition to his salary for very many years to come,' Mr. Gait- skell, never a man to he bashful when bad jokes are the order of the day, riposted (a fine word to use of an exchange which had all the delicacy and grace of a Bactrian camel suffering from a com- ri pound fracture of the spine, I must say), `I cannot forbear from reminding the Prime Minister of his great interest in the salary of the Leader of the Opposition.' All this was done to laughter which had the exact quality of that provided by the audience at a horror-film when the sixth Thing from Outer Space has finally been shrivelled up by the hero's death-ray; it was the hysterical laughter of relief. But it was carried to extra- ordinary lengths; Mr. Bernard Braine, for in- .-. stance, laughed so much he very nearly had a seizure. Then they all rushed lickety-spit to the bar, where happy, maudlin cries of `Good ol' Harold' mingled with the clink of celebratory glasses. But we are the people of England, and we have not spoken yet.

One hundred and twenty-two hours later (and don't forget that there was a weekend in the way) the Bill had received its second reading. No doubt about it; when the spirit moves these fellows they can move like lightning from the East unto the West. As for their Lordships, no sacrifice is too great when the public weal and three guineas a day are involved; they went so far as to sit on a Monday, and well over sixty of them at that. Whereat I grumbled mightily, but the chance of seeing the Earl of Home make a fool of himself (and there really is very little chance of seeing him do anything else) is one not lightly to be passed 11P. So there I was again, contemplating the Byzantine gilt from upstairs while the House of Peers was contemplating the Byzantine guilt from downstairs. Incidentally, Earl Attlee was causing a great commotion; happy in an expanse of red leather on the second bench, he suddenly decided to park himself on the front one, already crowded to suffocation (my word, Lord Silkin has put on Weight these last few years!); to this end he wriggled and wriggled and wriggled, and gave poor Lord Stansgate's ribs treatment that a Harle- quins lock-forward wouldn't stand for.

Then the Earl of Home, with the greatest pos- sible delicacy, rose to explain to their Lordships about the scheme for paying their expenses, up- to a maximum of three guineas a day. The only fault I could find with the noble Earl's exposition was that he seemed to be seriously in want of some- body to explain it to him first. I was, I may per- haps disclose, accosted in Battersea Park at four o'clock in the morning the other day, and re- proached with being unkind to the Earl of Home. With a courtly bow I owned to the charge, but ventured to wonder what else it was possible to be to him. I was then informed that whatever the Earl's faults he was at any rate a solid fellow. This, I may say, I have never doubted; the trouble Is that, as far as my own observations go, his to appears to begin at the fifth vertebra and to extend upwards to the medulla oblongata.

Next day, back on more familiar terrain, I sat open-mouthed while the House of Commons gave a display that would have made a hippopotamus retch. True, nobody played Pecksniff this time, but with the place stuffed to the rafters with Chadbands it was hardly necessary; there was enough soap in the speeches of Mr. Butler and Mr. Gaitskell combined to put the detergent manufacturers out of business for good. How im- portant it was that the public outside the House should understand exactly why Members' pay was being increased! How hard they all worked, and for what meed of ingratitude! How much more MPs of other nations get paid! And- Pelion on Ossa—how expensive postage is! This last from a Cabinet Minister of the Government which is going to raise postal charges next week!

Still, when Mr. Butler and Mr. Gaitskell had finished, only the hardiest spirits wanted to go on. Mr. Bowden had made it very clear that anybody attempting to contribute a single word from the Labour back benches would be for the high jump before the day was out, and Mr. Kenneth Pick- thorn, from the other side, could rest secure in the knowledge that his speech was pitched at such a level of total incomprehensibility that nobody could possibly understand it, let alone take excep- tion to it.

A little sense on the subject. MPs, considering the proportion of their pay that has to go on necessary expenses incurred in the course of their work, were for the most part clearly underpaid. It was therefore right and proper that they should help themselves to a little more, despite the length of the queue of people who deserve it far more than they would even if they worked as hard as they say they do. And short of a means test (Mr. Butler would have called it `undignified') this was the only way to do it. But did they really need to dress it up in so much cant? By the end of the display they seemed to be expecting a national vote of thanks for not making it a round two thousand. I fear that the pulse-takers have done their work ill; the nation seemed to me to be far less harrowed by the tales of MPs on the bread-line than the MPs themselves supposed. Poverty, after all, is relative; and there are some Members of whom one might say that it's no use supplying them with a bath, as they would only keep their gold in it. TAPER

Previous page

Previous page