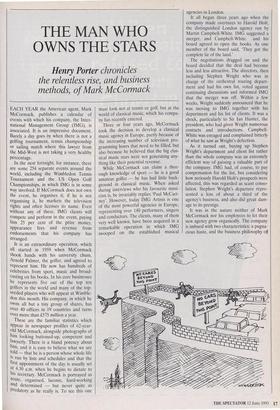

THE MAN WHO OWNS THE STARS

Henry Porter chronicles

the relentless rise, and business methods, of Mark McCormack

EACH YEAR the American agent, Mark McCormack, publishes a calendar of events with which his company, the Inter- national Management Group (IMG), is associated. It is an impressive document. Barely a day goes by when there is not a golfing tournament, tennis championship or sailing match where this lawyer from the Mid-West is not taking a very healthy percentage.

In the next fortnight, for instance, there are some 254 separate events around the world, including the Wimbledon Tennis Tournament and the US Open Golf Championships, in which IMG is in some way involved. If McCormack does not own the event, he organises it; if he is not organising it, he markets the television rights and often licenses its name. Even without any of these, IMG clients will compete and perform in the event, paying him 25 per cent of the prize money, appearance fees and revenue from endorsements that his company has arranged.

It is an extraordinary operation, which all started in 1959 when McCormack shook hands with his university chum, Arnold Palmer, the golfer, and agreed to represent him. He now has hundreds of Celebrities from sport, music and broad- casting on his books. In his core businesses he represents five out of the top ten golfers in the world and many of the top- seeded players who will appear at Wimble- don this month. His company, in which he owns all but a tiny group of shares, has over 40 offices in 19 countries and turns over more than £575 million a year. These are the familiar statistics which appear in newspaper profiles of 62-year- old McCormack, alongside photographs of him looking buttoned-up, competent and lawyerly. There is a bland potency about him, and it is easy to believe what we are told — that he is a person whose whole life is run by lists and schedules and that the first appointment of the day is usually set at 4.30 a.m. when he begins to dictate to his secretary. McCormack is portrayed as acute, organised, laconic, hard-working and determined — but never quite as Predatory as he really is. To see this one must look not at tennis or golf, but at the world of classical music, which his compa- ny has recently entered. Three or four years ago, McCormack took the decision to develop a classical music agency in Europe, partly because of the increasing number of television pro- gramming hours that need to be filled, but also because he believed that the big clas- sical music stars were not generating any- thing like their potential revenue. While McCormack can claim a thor- ough knowledge of sport — he is a good amateur golfer — he has had little back- ground in classical music. When asked during interviews who his favourite musi- cian is, he invariably replies 'Paul McCart- ney'. However, today IMG Artists is one of the most powerful agencies in Europe, representing over 140 performers, singers and conductors. The clients, many of them very well known, have been acquired in a remarkable operation in which IMG swooped on the established musical agencies in London.

It all began three years ago when the company made overtures to Harold Holt, the distinguished London agency run by Martin Campbell-White. IMG suggested a merger, and Campbell-White and his board agreed to open the books. As one member of the board said, 'They got the complete lie of the land.'

The negotiations dragged on and the board decided that the deal had become less and less attractive. The directors, then including Stephen Wright who was in charge of the orchestral touring depart- ment and had his own list, voted against continuing discussions and informed IMG that the merger was off. Within a few weeks, Wright suddenly announced that he was moving to IMG together with his department and his list of clients. It was a shock, particularly to Sir Ian Hunter, the president, who had given Wright numerous contacts and introductions. Campbell- White was enraged and complained bitterly of what he saw as Wright's defection.

As it turned out, buying up Stephen Wright's department and client list rather than the whole company was an extremely efficient way of gaining a valuable part of the company. IMG had, of course, to pay compensation for the list, but considering how seriously Harold Holt's prospects were affected, this was regarded as scant conso-

lation. Stephen Wright's departure repre- sented a loss of about a third of the agency's business, and also did great dam- age to its prestige.

It was in the nature neither of Mark McCormack nor his employees to let their new agency grow organically. The company is imbued with two characteristics: a pugna- cious haste, and the business philosophy of `vertical integration', which broadly means having a piece of every part of the action in a particular field. Long ago, McCorma- ck drily observed that while one of his clients, Bjorn Borg, could break a leg, Wimbledon could not. In the Eighties, he moved into tournaments in a big way, organising sponsorship for whole competi- tions, running a corporate entertainment business, licensing the name Wimbledon and marketing the world television rights. (He caused a furore in Germany when he sold the German television rights to a cable station in 1989, when Steffi Graf and Boris Becker won the two singles titles.) The effectiveness of IMG's policy of ver- tical integration is best seen at an event like the World Match Play Championships at Wentworth, which McCormack invented a few years ago. At the heart of the event there is a squad of IMG players who bring with them huge sponsorship deals (Greg Norman, for instance, earns about $5 mil- lion a year). IMG sells the sponsorship of the tournament and the television cover- age, which go to the BBC with a commen- tary by Peter Alliss (another IMG client) and McCormack himself. Almost nothing moves at Wentworth during that week without McCormack taking a percentage.

This, then, was how IMG conceived of exploiting the music business. However, its employees were never so crude as to believe that they would have the instant success McCormack had had in the Sixties representing first Arnold Palmer, then Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus. They understood also that they could not simply plaster a soprano with manufacturer's logos, but that revenue would be generat- ed instead by numerous sidelines. To this end, they started a recording label, devel- oped a video business and, most important of all, created a number of events where their stars perform for television notably the Hampton Court Palace Festi- val (between 12 and 19 June) and the Sudeley Castle summer festival at the end of July.

But events need singers, and IMG had very few. It was then that McCormack delivered his greatest shock to the classical music world. With fewer than 50 clients, IMG artists began to look around for more. To lure separate stars away from these agencies would have been a long and fruitless process. Instead, IMG went after the agents themselves and alighted on two key people, Tom Graham, the American director of Harrison Parrott, and his long- standing girlfriend, Diana Mulgan, the co- managing director of Lies Askonas Ltd. Neither owned an agency but both were directors and highly prized employees.

IMG proposed that they both join McCormack's stable and bring their lists with them. No one at the two agencies sensed anything wrong, least of all Jasper Parrott, the managing director and founder of Harrison Parrott, who had been consid- ering ways of giving Graham 'a greater scope and freedom'.

One morning last December, Graham made an appointment to see Parrott with- out saying what he wanted to talk about. He opened the meeting by announcing he would be leaving the agency with his 60 clients, mostly singers, and his staff of three. Parrott was aghast. Graham's list represented two thirds of his clients. 'It was entirely improper, and you can quote me on that,' recalled Parrott. 'He was entirely trusted and had unlimited discretion in the way he ran things. He gave me no opportu- nity to meet the offer made by McCorma- ck, nor to find some other way of retaining him. He made it clear that this was the decision that had been taken. He had been made an offer which he couldn't refuse there were other sweeteners, like a mem- bership of a smart golf-club — things like that.'

At the same time as Graham and Parrott were meeting, Diana Mulgan announced to her co-managing director of Lies Askonas Ltd, Robert Rattray, that she, too, was going to IMG and taking with her a list of 40 singers. Rattray was similarly appalled and so too was the founder of the firm, Lies Askonas herself, who had done much for Mulgan's career.

Both Parrott and Rattray were sanguine about the commercial competition. Parrott said, 'IMG is a very tough and ruthless company and one might reasonably expect them to do something like this.' What nei- ther much liked was the idea that they had been working with Graham and Mulgan for many weeks while the couple were negotiating to remove their client lists. What made it more painful was that this covert operation must have at some stage included discussion with the clients well before Parrott and Rattray had any idea of the mass defection. The agreed sum paid to both agencies did not sweeten the pill. `It left a very nasty taste in the mouth,' said a member of Parrott's staff.

So, in the space of a few weeks, McCor- mack's agency had increased its client list from 50 to nearly 150 singers, musicians, conductors and producers. Names such as Anne-Sophie von Otter, Robert Lloyd, Neil Shicoff, Barbara Bonney, Felicity Palmer, Thomas Hampson and Willard White joined James Galway, Jonathan Miller, John Eliot Gardiner and Sir Neville Marriner who already were ensconced at IMG.

It is surprising that so few singers stayed with their old firms. 'This was explained to me by an opera singer,' said Jasper Par- rott. 'Singers are very isolated. Their only life-line is to the individual that they are dealing with. They are extremely loyal to the agent, not the agency.'

This is true, but the fact remains that McCormack's business has always princi- pally been the management of celebrities and at this he is very good. Many of the performers found the range of his service extremely attractive. McCormack's cuts are very high — higher than any other well-known agent — but in return he arranges his clients' tax affairs, handles pensions and life insurance policies, pays school fees and sorts out every conceivable legal problem. It is not unknown for IMG to thrash out a divorce settlement on behalf of a client.

Although there is an eerie sense of con- trol at IMG — at times one is reminded of a modern American cult when one talks to its employees — the clients seem mostly happy about the arrangements. Tom Gra- ham is zealous in his praise. 'The resources for client management are here. Whether those clients are sportsmen or entertainers, they benefit from the tax expertise, the public relations expertise, the financial expertise, the television expertise, the other media expertise. Plug- ging in to that sort of infrastructure the singers that we brought was not difficult.' Graham, although facing deep hostility from some quarters (there is some support for Parrott's wish to see him ousted from his position as chairman of the British Association of Concert Agents), is without regret. never had any complaints or any- thing like that with Harrison Parrott. I think when you are a grandfather and aged 50 it is time for change. I hope that there is no bad feeling and I hope people under- stand that what we did was in all our best interests.'

McCormack seems to have pulled off the perfect coup, but there is one great doubt. After this huge commitment of funds, it is by no means guaranteed that McCormack will reap from music the profits he has in golf and tennis. People outside the organi- sation believe he may have overstretched himself, because it is difficult to build up a musician to the earning power that McCor- mack needs to cover his overheads. 'You can't just make a star overnight,' said Andrew Green who writes for Classical Music Magazine. 'Television companies want people we have all heard of. What matters is the name, not the fact that some- body is on your books.'

And there were some doubting voices within IMG. A crucial voice, but apparently not one well listened to, belonged to Hazel Wright, who was in charge of television sales and co-production for IMG Artists. Seven weeks ago, she left IMG to join the BBC.

It may be, as many hope, that the agent has bitten off more than he can chew. One thing is certain, though: the world of classi- cal music has been changed for ever in Europe.

Previous page

Previous page