The image of the hawk

Andrew Joynes

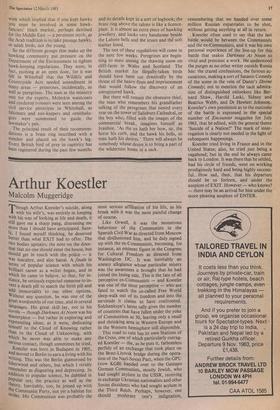

T n a field on the edge of Salisbury Plain, the wind comes from the north- east, skimming an extra chill across the Hampshire/Wiltshire border. A teenage boy stands in the middle of the field, peer- ing at the sky, and swinging a leather lump at the end of a rope like a cowboy preparing a lasso. Suddenly he slows the circle, shouts, and pitches the lump upwards into the air, where it is met by a blurred object that has travelled downwards with the speed and trajectory of a meteorite. An un- tidy combination of shapes falls to the ground, and resolves itself into a blue-grey bird hunched on the ground tearing at a piece of raw meat. A male peregrine — a tiercel — has returned to the lure.

Crouched on top of an old chicken shed a large hawk with the black and russet col- ouring of a Rhode Island Red peers with a reptilian intensity at a man a hundred yards away. The man raises his arm and whistles. The bird, a Harris Hawk from Mexico, swoops off the shed, flies low along the ground, and lifts delicately onto a heavily gloved fist. 'He's like a dog with wings,' says the man happily, 'he always comes when you call him.'

Young Ashley Smith and his father — partners in the Hawk Conservancy at Weyhill — have been flying their hawks every day this winter, except when the wind is so strong that the shouts of command cannot be heard. Then there is a danger that a bird travelling at a mile a minute will be swept so far away that the almost psychic connection with its master is dangerously weakened. Later this year, when the Hawk Conservancy opens again to the public, schoolchildren will mass behind a wooden barrier on summer afternoons and watch peregrines, Lanner falcons and goshawks circling and diving in an aerial display that has the perfect appeal of the Red Arrows without the jet noise.

Winter and summer, the Smiths have a wary, equivocal attitude towards the urban public before whom they display the beauty of their birds — rather as a missibnary might preach a graceful theological doctrine to a tribe of rather coarse savages. On fine summer days, when the hawks go spiralling up in the thermals, they are aware of a response, behind the exclamations of delight, that amounts almost to lust. Children talk of 'having a go' on the little kestrels that the Smiths permit to be handl- 'He's a funny old stick.' ed, rather as they might demand a go on the dodgems at a funfair. Their parents mur- mur that its's all like a television sequence. The hawk has become an advertising man's logo, a symbol to the video generation of wilderness and virility; in the commercial breaks the symbol is used to sell everything from hairspray to canned lager.

But it is superficial to say that the adman alone has created the mystique of the hawk. In his astuteness, he has merely tapped a reservoir of human desire that was at its deepest in the Middle Ages, when hawking was so popular a pastime that it had to be strictly regulated lest it damage the hierar- chy of society. Only the nobly-born were permitted to fly a peregrine falcon, for in- stance; only a yeoman could fly a goshawk. A priest had to settle for a sparrowhawk, and a knave could rise no higher than a kestrel (which caught nothing but beetles and voles). In this way, the rigid structure of society was maintained and the supply of hawks and game neatly controlled. Inciden- tally, on the continent, where there was a tendency to be a bit flash — in the matter of titles as well as hawks — an extra tier was added: only an Emperor could ride out with a Golden Eagle on his wrist.

The unbuttoned falconer will talk com- placently about the enrichment that his an- cient sport has brought to the English language. Words like 'haggard' (an old hawk), 'mantle' (the spread wings above the prey) and 'hoodwink' (the covering of a hawk's eyes with a dainty hood) all derive. from hawking terminology. Every country pub called 'The Bird in Hand' reflects the relieved pride of a man whose darling has returned from heaven to his mortal fist. MY favourite derived term, incidentally, Is 'cadger': it originally meant the man who carried the oblong frame on which hawks in the field were parked. Carrying the frame up and down the moorland, he was suppos- ed to keep account of the number of times each bird had flown; in return for which easy information he received a tip. A few years ago, a fear grew among responsible hawk-keepers like the Smiths — and among the tight-knit group of field- sport falconers who use hawks in coordina- tion with pointer dogs to take grouse, par- tridge and hare — that the growing public interest in birds of prey would lead to an in- creasing number of ill-qualified people keeping ill-maintained birds. There is a story of a teenager in Birmingham who used to walk round a city centre Woolworths with a demented and woebegone goshawk on his wrist.

The fear was borne out by the increasing number of thefts from falcon eyries. The peregrine, the aristocrats' bird, has been particularly at risk in this respect: in the last year, for instance, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds recorded thefts of young birds, 'eyases', from over sixty ledges in Great Britain. Newspaper reports or court cases mentioned inflated estimates of the amount a thief could hope to ob- tain for a young bird. This increased the falconers' resentment at the nudge and the wink which implied that if you kept hawks You must be involved in some hawk- fanciers' black market, perhaps destined for the Middle East — a persistent myth, as the Arab tradition is to take passage hawks, or adult birds, not the young.

So the different groups that make up the hawking community put pressure on the Department of the Environment to tighten hawk-keeping regulations. They were, in fact, pushing at an open door, for it was felt in Whitehall that the Wildlife and Countryside Acts needed amendment in Many areas — primroses, incidentally, as well as peregrines. The men at the ministry sent for the experts. Moleskin waistcoats and corduroy trousers were seen among the civil service pinstripes in Whitehall, as falconers and zoo-keepers and ornitholo- gists were summoned to guide the lawmaker's pen.

The principal result of their recommen- dations is a brass ring inscribed with a number and placed on the hawk's leg. Every British bird of prey in captiVity has been registered during the past few months and its details kept in a sort of logbook; the brass ring above the talons is like a licence- plate. It is almost an extra piece of hawking jewellery, and looks very handsome beside the Lahore bells and the jesses and the soft leather hood.

The test of these regulations will come in the next few weeks. Peregrines are begin- ning to mate among the thawing snow on cliff-faces in Wales and Scotland. The British market for illegally-taken birds should have been cut drastically by the threat of the heavy fines and imprisonment that would follow the discovery of an unregistered hawk.

But there will remain the obsessive thief, the man who remembers his grandfather talking of the peregrines that nested every year on the tower of Salisbury Cathedral, or the boy who, filled with the images of the commercial break, imagines himself as Ivanhoe. 'As the ox hath her bow, sir, the horse his curb, and the hawk his bells, so man hath his desires.' There will always be somebody whose desire is to bring a part of the wilderness home in a sack.

Previous page

Previous page