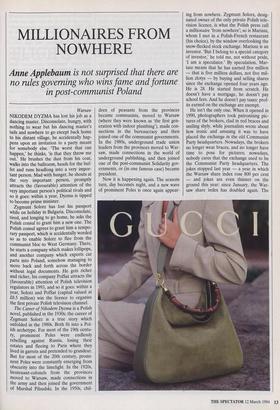

MILLIONAIRES FROM NOWHERE

Anne Applebaum is not surprised that there are

no rules governing who wins fame and fortune in post-communist Poland

Warsaw NIKODEM DYZMA has lost his job as a dancing master. Disconsolate, hungry, with nothing to wear but his dancing master's tails and nowhere to go except back home to his distant village, he accidentally hap- pens upon an invitation to a party meant for somebody else. 'The worst that can happen,' he thinks, 'is that they throw me out.' He brushes the dust from his coat, walks into the ballroom, heads for the buf- fet and runs headlong into a very impor- tant person. Mad with hunger, he shouts at the very important person, promptly attracts the (favourable) attention of the very important person's political rivals and so it goes: within a year, Dyzma is tipped to become prime minister. Zygmunt Solorz has lost his passport while on holiday in Bulgaria. Disconsolate, tired, and longing to go home, he asks the Polish consul to grant him a new one. The Polish consul agrees to grant him a tempo- rary passport, which is accidentally worded so as to enable Solorz to flee from the communist bloc to West Germany. There, he starts a company which makes lollipops, and another company which exports car parts into Poland, somehow managing to move back and forth across the border without legal documents. He gets richer and richer, his company PolSat attracts the (favourable) attention of Polish television regulators in 1993, and so it goes: within a year, Solorz and PolSat (capital valued at £8.5 million) win the licence to organise the first private Polish television channel. The Career of Nikodem Dyzma is a Polish novel, published in the 1930s; the career of Zygmunt Solorz is a true story which unfolded in the 1980s. Both fit into a Pol- ish archetype. For most of the 19th centu- ry, prominent Poles were endlessly rebelling against Russia, losing their estates and fleeing to Paris where they lived in garrets and pretended to grandeur. But for most of the 20th century, promi- nent Poles were constantly emerging from obscurity into the limelight. In the 1920s, lieutenant-colonels from the provinces moved to Warsaw, made connections in the army and then joined the government of Marshal Pilsudski. In the 1950s, chil- dren of peasants from the provinces became communists, moved to Warsaw (where they were known as 'the first gen- eration with indoor plumbing'), made con- nections in the bureaucracy and then joined one of the communist governments. In the 1980s, underground trade union leaders from the provinces moved to War- saw, made connections in the world of underground publishing, and then joined one of the post-communist Solidarity gov- ernments, or (in one famous case) became president.

Now it is happening again. The seasons turn, day becomes night, and a new wave of prominent Poles is once again appear- ing from nowhere. Zygmunt Solorz, desig- nated owner of the only private Polish tele- vision licence, is what the Polish press call a millionaire 'from nowhere'; so is Mariusz, whom I met in a Polish-French restaurant (his choice), by the window overlooking the snow-flecked stock exchange. Mariusz is an investor. 'But I belong to a special category of investor,' he told me, not without pride, `I am a speculator.' By speculation, Mar- iusz means that he has earned five million — that is five million dollars, not five mil- lion zlotys — by buying and selling shares since the exchange opened four years ago. He is 28. He started from scratch. He doesn't have a mortgage, he doesn't pay school fees. And he doesn't pay taxes: prof- its earned on the exchange are exempt.

He isn't the only one. When it opened in 1990, photographers took patronising pic- tures of the brokers, clad in red braces and smiling shyly, while journalists wrote about how ironic and amusing it was to have placed the exchange in the old Communist Party headquarters. Nowadays, the brokers no longer wear braces, and no longer have time to pose for pictures; nowadays, nobody cares that the exchange used to be the Communist Party headquarters. The jokes stopped last year — a year in which the Warsaw share index rose 800 per cent — and jokes are even thinner on the ground this year: since January, the War- saw share index has doubled again. The number of deals now done on the Warsaw exchange is close to the number of deals done on the London exchange, a fact which is mostly accounted for by the 400,000 registered individual investors the heart of the future Polish ruling class — each of whom is ringing his broker and buying or selling one or two shares every day.

It is all just a bit too flash for the tastes of the World Bank types who set up the exchange; most would prefer something more staid, more western, less successful. `This is not a lottery,' the chairman of the exchange told me, almost fuming. He is often quoted complaining that prices are `too high', just as august members of the finance ministry are endlessly telling the newspapers that prices 'must drop'.

In the beginning, such dire pronounce- ments did have an effect on the market. Now, everyone ignores them. 'The beauty of our market,' one investor explained gleefully, 'is that it does not follow any rules, whatsoever.' Western investment funds arrive in Warsaw, buy stock when they think it cheap and sell when they think it overpriced. Afterwards, they find that share prices have doubled again, con- trary to all logical expectations. Inevitably it is the Poles, particularly those who began by investing their grandmothers' savings, who have made the most money.

One suspects, in fact, that it is precisely the success of people who are not sup- posed to succeed which irritates the Polish political establishment most of all. Hang- ing about the Warsaw stock exchange on any given day are not Swiss bankers and Poles who have been to Harvard Business School (the sort of people whom august members of the finance ministry would like to see there) but rather former money-changers and black-marketeers, doctors and university professors, a sprin- kling of teenagers and one old man who is notorious for the faint rotting smell which seeps out of his ancient sheepskin jacket. `He's never spent a hundred dollars on a new coat before,' said Mariusz, who explained that the man is, like himself, a dollar millionaire. 'He thinks a hundred dollars is too much money, that prices these days are too high.'

Not that all of those making money are even so easy to identify. The recent pri- vatisation of a Polish bank was accompa- nied by the unofficial circulation of what was dubbed the Swindler's List: the list of politicians who (illegally) managed to buy more shares, at lower prices, than ordinary applicants were allowed. In addition to the Swindler's List, newspapers also published names of bank employees who (legally) bought more shares, at lower prices — but then rigged the system so that no one but themselves could sell shares during the first few days of trading, when stock prices multiplied by a factor of 16. This is pre- cisely the sort of thing which makes 'nor- mal' investors— Swiss bankers and their ilk — run for cover.

Curiously, past business credentials pro- vide no clue as to who will succeed in the unpredictable present. In the old days, shortages were such that anyone who could sell anything made money; now, with kiwis and ladies razors and German lawn-mowers flooding over the borders, the small companies which were allowed to flourish in the final years of the commu- nist regime are disappearing one by one. They have been replaced by new compa- nies which are either more competitive, or more corrupt, or both.

But if past business credentials are no guide to present success, then neither are anyone's past political beliefs. There are hopeless, disorganised former dissidents; and then there are the owners of the daily `I can't change the Channel.' Gazeta Wyborcza, ex-dissident journalists to a man, all of whom are now very rich peo- ple. There are unemployed, unemployable ex-communist flunkies and then there is Jerzy Urban, the ex-communist govern- ment press spokesman, who now runs a pornographic scandal sheet, and is also a very rich man. Good underground trade unionists have proved poor managers; unpleasant communist bureaucrats have proved more than adept at the art of making deals. None of the old political categories matters anymore, since new Nikodem Dyz- mas, millionaires from nowhere, appear every day, winning fame and fortune through merit, or luck, or sleaze.

Perhaps it is not surprising then that there are many who continue to long for the simplicity, the clarity and the controlla- bility of the past. 'What is it about this stock market?' an irate Pole wrote in a let- ter to the editor of a Warsaw daily. 'It keeps going up and then down and then up again. Can't the government do something to control it?'

Previous page

Previous page