AN UNACCEPTED AUTHENTIC

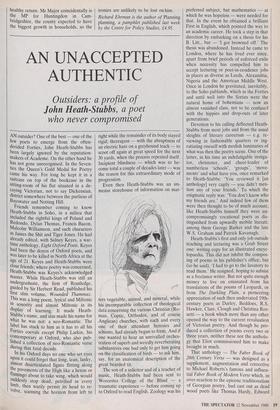

Outsiders: a profile of

John Heath-Stubbs, a poet

who never compromised

AN outsider? One of the best — one of the few poets to emerge from the often- derided Forties, John Heath-Stubbs has been largely ignored by the reputation- makers of Academe. On the other hand he has not gone unrecognised. In the Seven- ties the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry came his way. For long he kept it in a suitcase on top of the bookcase in the sitting-room of his flat situated in a de- caying Victorian, not to say Dickensian, district somewhere between the purlieus of Bayswater and Notting Hill.

Friends remember coming to know Heath-Stubbs in Soho, in a milieu that included the rightful kings of Poland and Redondo, Dylan Thomas, Francis Bacon, Malcolm Williamson, and such characters as James the Shit and Tiger Jones. He had already edited, with Sidney Keyes, a war- time anthology, Eight Oxford Poets. Keyes had been the doyen of Oxford poets, and was later to be killed in North Africa at the age of 21. Keyes and Heath-Stubbs were Close friends; where poetry was concerned, Heath-Stubbs was Keyes's acknowledged master. While Heath-Stubbs was still an undergraduate, the firm of Routledge, guided by Sir Herbert Read, published his first slim volume, Wounded Thammuz. This was a long poem, lyrical and Miltonic in sonority and almost Miltonic in its display of learning. It made Heath- Stubbs's name, and alas made his name for What he was not: a neo-Romantic. The label has stuck to him as it has to all his Forties coevals except Philip Larkin, his contemporary at Oxford, who also pub- lished a collection of neo-Romantic verse during that fatal decade.

In his Oxford days no one who set eyes Upon it could forget that long, lean, lanky, almost disarticulated figure flitting along the pavements of the High like a heron or flamingo about to take wing, which would suddenly stop dead, petrified in every limb, then warily permit its head to re- volve, scanning the horizon from left to right while the remainder of its body stayed rigid; thereupon — with the abruptness of an electric hare on a greyhound track — to scoot off again at great speed for the next 30 yards, when the process repeated itself. Incipient blindness — which was to be- come total a couple of decades later — was the reason for this extraordinary mode of progression. Even then Heath-Stubbs was an im- mense storehouse of information on mat- ters vegetable, animal, and mineral, while his incomparable collection of theological data concerning the various Christian (Ro- man, Coptic, Orthodox, and of course Anglican) churches, with each and every one of their attendant heresies and schisms, had already begun to form. And if one wanted to hear an unrivalled orches- tration of superb and weirdly reverberating substantives one had only to get him going on the classification of birds — to ask him, say, for an anatomical description of the great bearded tit. The son of a solicitor and of a teacher of music, Heath-Stubbs had been sent to Worcester College of the Blind — a traumatic experience — before coming up to Oxford to read English. Zoology was his preferred subject, but mathematics — at which he was hopeless — were needed for that. In the event he obtained a brilliant First in English, which pointed the way to an academic career. He took a step in that direction by embarking on a thesis for his B. Litt., but — 'I got browned off.' The thesis was abandoned. Instead he came to London, where he has lived ever since, apart from brief periods of enforced exile when necessity has compelled him to accept lecturing or poet-in-residence jobs in places as diverse as Leeds, Alexandria, Nigeria and the American Middle West. Once in London he gravitated, inevitably, to the Soho publands, which in the Forties and until well into the Sixties were the natural home of bohemians — now an almost vanished class, not to be confused with the hippies and drop-outs of later generations.

Devotion to his calling deflected Heath- Stubbs from most jobs and from the usual sleights of literary careerism — e.g. re- viewing in fashionable quarters or ing- ratiating oneself with modish luminaries of what was then the poetry scene. One of the latter, in his time an indefatigable instiga- tor, christener, and cheer-leader of numberless 'schools', 'groups', 'move- ments' and what have you, once remarked to Heath-Stubbs: 'You reviewed it [an anthology] very cagily — you didn't men- tion any of your friends.' To which the enigmatic reply was: 'You don't know who my friends are.' And indeed few of them were then thought to be of much account; like Heath-Stubbs himself they were un- compromisingly vocational poets as dis- tinguished from upwardly mobile literati; among them George Barker and the late W.S. Graham and Patrick Kavanagh.

Heath-Stubbs's first and only job outside teaching and lecturing was a Grub Street one: writing copy for an illustrated encyc- lopaedia. This did not inhibit the compos- ing of poems in his publisher's office; but (so he said), 'I had to go to the lavatory to read them,' He resigned, hoping to subsist as a freelance writer. But not quite enough money to live on emanated from his translations of the poems of Leopardi, or from The Darkling Plain, a pioneering. appreciation of such then underrated 19th- century poets as Darley, Beddoes, R.S. Hawker, Clare, Clough and Christina Ros- setti — a book which more than any other opened the way to the current revaluation of Victorian poetry. And though he pro- duced a collection of poems every two or three years, neither these nor the antholo- gy that Eliot commissioned him to make brought in much.

That anthology — The Faber Book of 20th Century Verse — was designed as a

supplement, augmentation and corrective

to Michael Roberts's famous and influen- tial Faber Book of Modern Verse which, in

over-reaction to the epicene traditionalism of Georgian poetry, had cast out as dead wood poets like Thomas Hardy, Edward

Thomas, A.E. Housman and even Hugh MacDiarmid. Their inclusion, and the ex- clusion of one or two vogue names, did Heath-Stubbs no good in quarters where the accepted is mistaken for the authentic. Nor did his jeux &esprit, mocking some of the more egregious of his contemporaries, the satiric 'Triumph of the Muse' and 'Poet of Bray'. In fact these comic pasquinades frightened his publisher's poetry reader into dropping Heath-Stubbs from their list altogether. A classic boob, as Heath- Stubbs's next book, which perforce he offered elsewhere, turned out to be his chef-d'oeuvre, the Arthurian mini-epic Artorius, a work that won him the Queen's Gold Medal.

Productivity and virtuosity have been two of Heath-Stubbs's qualities — there is no metre or verse-form that he has not successfully essayed, as his fat volume of collected poems, published earlier this year, bears witness. His great virtue, most apparent in his later poems and character- istic of his conversation, is a dry and self-deflating humour. The American poet Donald Hall tells this story:

Someone from a newspaper was interviewing him in a bar. The interviewer asked for the names of his books. John had just given the name of the first volume when I butted in. I decided that the interviewer should take not only the titles from John. 'Dates, too,' I interjected. John's face crumpled for a mo- ment, then he smiled gingerly. 'Yes, I suppose it does.'

Two further anecdotes. Once, in a taxi, a friend, who like him had taken a drop, quoted: 'In vino veritas', adding, 'See if you can translate that.' Without hesitation Heath-Stubbs replied, 'No bunk / When drunk.' The other has to do with his physical crucifix, a hereditary tendency to blindness, which he has carried with drol- lery and courage. One eye has always been useless; the other slowly failed. This some- times brought him into trouble. On one memorable occasion he rang a friend's doorbell at what seemed an unconscion- ably early hour: they had both been to a party at Islington the night before. 'John, you look pretty woebegone. What hap- pened?"Well, you remember that party last night? It was a very dull one, but I stayed on after you left — too long, because when I made up my mind to leave, the last bus had gone. So I started to walk home. And on the way I found I wanted to pee. All the public lavatories were shut, but I found a dark corner that I thought would do, so I went into it. Only it wasn't a dark corner. It was a policeman.'

Heath-Stubbs's attitude to the extinction of his eyesight has been to view it as an inconvenience, not a calamity; a hind- rance, not an impediment. As before, he lives and manages for himself in his bache- lor flat. Unable to write, he memorises poems as he composes them, to dictate later to some visiting friend. At 70 his muse is as fecund as ever.

Previous page

Previous page