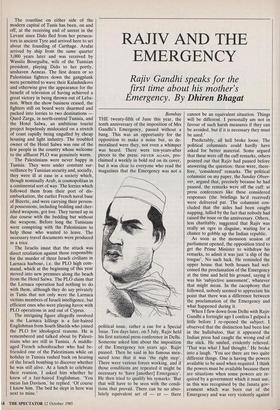

RAJIV AND THE EMERGENCY

Rajiv Gandhi speaks for the first time about his mother's

Emergency. By Dhiren Bhagat Bombay THE twenty-fifth of June this year, the tenth anniversary of the imposition of Mrs Gandhi's Emergency, passed without a bang. This was an opportunity for the opposition to make a noise but, so de- moralised were they, not even a whimper was heard. There were ten-years-after pieces to the press: NEVER AGAIN, pro- claimed a weekly in bold red on its cover, but it was clear to everyone who read the magazines that the Emergency was not a political issue, rather a cue for a Special Issue. Ten days later, on 5 July, Rajiv held his first national press conference in Delhi. Someone asked him about the imposition of the Emergency ten years ago. Rajiv paused. Then he said in his famous mea-. sured tone that it was 'the right step'. There were various forces working. and if those conditions are repeated it might be necessary to 'have [another] Emergency'. He then tried to qualify his remarks: 'But that will have to be seen with the condi- tions that prevail. There can be no abso- lutely equivalent set of — er — there cannot be an equivalent situation. Things will be different. I personally am not in favour of such harsh measures if they can be avoided, but if it is necessary they must be used.'

Predictably, all hell broke loose. The political columnists could hardly have asked for better material. Some argued that these were off the cuff remarks, others pointed out that Rajiv had paused before answering the question: these were, there- fore, 'considered' remarks. The political columnist on my paper, the Sunday Obser- ver, argued that, precisely because he had paused, the remarks were off the cuff: at press conferences like these considered responses (the briefings he'd received) were delivered pat. The columnist con- cluded that the aides had been caught napping, lulled by the fact that nobody had raised the issue on the anniversary. Others, less charitably, suggested that Rajiv was really an ogre in disguise, waiting for a chance to gobble up the Indian republic.

As soon as the monsoon session of parliament opened, the opposition tried to get the Prime Minister to withdraw his remarks, to admit it was just 'a slip of the tongue'. No such luck. He reminded the upper house that both houses had wel- comed the proclamation of the Emergency at the time and held his ground, saying it was his 'subjective assessment', whatever that might mean. In the cacophony that followed, nobody seemed to appreciate his point that there was a difference between the proclamation of the Emergency and what happened during it.

When I flew down from Delhi with Rajiv Gandhi a fortnight ago I confess I gulped a little before I re-opened the subject. I observed that the distinction had been lost in the hullabaloo, that it appeared the Indian press had caught the wrong end of the stick. He smiled, evidently relieved. `That was what I had thought.' He broke into a laugh. 'You see there are two quite different things. One is having the powers available to be used when required. I think the powers must be available because there are situations when some powers are re- quired by a government which it must use, as this was recognised by the Janata gov- ernment which was born out of the Emergency and was very violently against an Emergency. When they amended the constitution they left this bit, they didn't remove it,'

Was there anything in the way the Emergency developed that he didn't approve of? 'A lot of things just went wrong.' What sort of things went wrong? `Basically I think the government lost control of the administration, of what the state governments, of what the other politi- cians were doing. What it also did was cut off feedback.' Was he referring to the censorship of the press? 'Well, yes, cen- sorship. And maybe a certain amount of fear psychosis.' Might not these things happen in any emergency? 'Only if it goes on for an extended period. If it had finished off in a few months it would have been okay.' At the time had he been in favour of lifting the Emergency early? `Well, I was not very much for the pro- clamation of the Emergency at the begin- ning. But there was a very positive fall-out in the infrastructure and other sort of development areas in that period.' I began to grow wary: my ear could detect the Indian Administrative Service gobbledy- gook.

When did he think the Emergency should have been lifted — the middle of 1976? He paused a bit, tried to avoid anything so specific, then complied. 'Six months would have been enough.' What did he think of the family planning pro- gramme? 'That went totally out of hand.' When did it go out of hand? But there also I don't know how much of it went out of hand and how much it was believed to have gone out of hand — it is very difficult to draw a line. But the fact is that propaganda-wise it very definitely went out of hand.'

Sanjay had thought it a mistake to call the elections in 1977: most accounts we have suggest he thought Congress would lose, at any rate that it was not worth taking the chance. Had Rajiv thought it the right decision to call the elections? 'Yes. I think the elections should have been held on schedule a year earlier. But if you ask me whether the Congress was going to win or lose I knew the Congress was going to lose.' Had he told his mother as much? 'I told my mother. So did my brother.' What did she think? 'I don't know what she thought. I don't think she was sure of winning, I mean that I know.'

Two weeks after the Allahabad high court judgment which unseated her from parliament, Mrs Gandhi imprisoned her political opponents, censored the press and proclaimed a state of Emergency in the country. I asked Rajiv what he had felt about the timing, after all did he not think it important that Caesar's wife be seen. to be chaste? 'I don't know. I have not had access to what sort of intelligence the government was getting at that time. My mother didn't talk to us about it. And of course without that it is difficult to say what really, what sort of pressure they were under. Because there had been just about that time a call by Jayaprakash Narayan for total revolution, including revolt in the armed forces and you know these sort of things.'

Writing about the Punjab elections last month, I had alluded to the results of a poll conducted in the four big cities of India in June which had tried to collect people's attitudes towards the Emergency. (`Rajiv opts for havoc', Spectator, 7 September). Sixty-seven per cent of the respondents thought the 1975-77 Emergency had been a good thing for the country and 65 per cent said they would support another emerg- ency. I reeled off some of these figures and asked Rajiv if he would care to comment on them. He put on his serious Boy Scout face. 'It means that basically people want discipline, which is sadly lacking in India today. I don't want to go into the reasons why it is lacking because there are too many things. It will take a long time. Discipline is one of the most important things a country has to have.'

Mercifully for most of the time we spoke he did away with the Boy Scout look. We were in his cabin in an Indian Air Force Boeing 737. He was informal, unostenta- tious. As anyone who's ever watched him on television knows, he is mostly shy, affable, amiable. Earlier, Rajiv's press aide had suggested to me that I speak to him about 'the politics of confrontation'. I had thanked him politely but for the life of me I couldn't think of anything more boring. I was more interested in making Rajiv reminisce, recollect, say anything really except what he had been briefed to say by his IAS advisers. 'You can try,' the aide had warned, 'but you'll most likely come a cropper. He isn't a man who's interested in himself.' It is true that Rajiv is not the world's greatest raconteur, but what impressed me was the frankness with which he spoke about himself. Mrs Gandhi always struck one as wily and secretive, as someone who had something to hide. A contemporary of hers at Somerville (who went on to become a senior civil servant in the education ministry in New Delhi) once told me that Mrs Gandhi had failed Latin Responsions twice and in consequence had been sent down. Yet Mrs Gandhi had chosen to conceal this: in no biography or interview was this ever mentioned. But when I spoke to Rajiv about his time at Cambridge it was very different.

`How long were you there?'

`You'll have to be vetted.' `Three years — 1962-65.'

`What degree did you read for?'

`Mechanical science.'

`May I ask what class you got?'

'Zero, flunked out.'

'What do you mean?'

'I didn't get a degree.'

'You didn't do it, or. . . ?'

'No, I did it but I didn't get a degree. I didn't do well enough.'

Mrs Gandhi had been miserable at Ox- ford: Rajiv clearly enjoyed himself at Cambridge. He had lots of friends, read `the normal rubbishy books', heard a lot of Miles Davis, Coltrane and Stan Getz (Not the newer Stan Getz but the older Stan Getz'). What had England been like? No profundities but a cheerful laugh. 'It was great fun, certainly.'

Appearances, of course, can deceive. The jolly round man in the pub may have just drowned his wife in a boiling vat, the wolf may have been told by his fashion consultant that sheepskin most becomes him. All this is possible. But I left the plane convinced that Rajiv's frank, cheerful manner has something to do with my hunch that we in India are unlikely to have another authoritarian emergency imposed on us.

Previous page

Previous page