MACAVITY AND THE McKINSEY MAFIA

The clannish consultants' performance

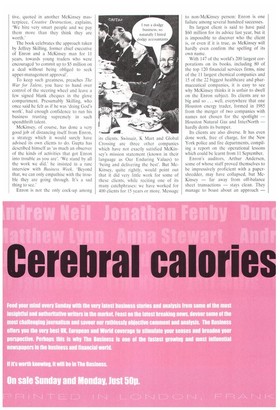

cells are everywhere and nowhere, says Becky Barrow

THE biggest hurdle when trying to understand McKinsey & Company is not that the high priest of management consultancy suffers from an allergy to journalists. It is that they do not speak English.

A regional dialect of ancient Armenian would be easier for a non-consultant to interpret than sentences such as 'the servant-leader model doesn't quite jibe with power' or we serve a lot of leader institutions, but at the same time there are a lot of white spaces'.

As ex-McKinsey groupies, William Hague, Archie Norman, Sir Howard Davies and Adair Turner, not forgetting the Serbian finance minister Bozidar Djelic, should understand what 'the Firm' means by 'performance cells' and 'engagement descriptions'.

At least Rajat Gupta, McKinsey's managing partner who completes the third of his three-year terms next summer, has the good grace to confess, 'I could be more direct and forthright.' Oftentimes,' says the 53-year-old, who grew up in New Delhi, the first non-American-born boss of the mighty McKinsey, 'that means that I'm not as direct as I probably should he, and sometimes my colleagues, of course, find that a very frustrating process, and they think, "Why don't you say what you exactly mean?"

Armed with a dictionary and preferably wearing a baseball cap to get you in the mood, there is one very direct question that people have been daring to ask McKinsey, a company with the secrecy of the royal family and the arrogance of Lord Irvine. Why, it has been asked, can McKinsey manage to advise Enron for nearly two decades, allegedly enjoying up to $10 million in annual fee income, but emerge without a scratch from the American energy trader's spectacular demise?

It was, suggested one business newspaper, a case as miraculous as the feats of T.S. Eliot's Macavity, the Mystery Cat: 'He's the bafflement of Scotland Yard, the Flying Squad's despair/For when they reach the scene of crime — Macavity's not there!'

McKinsey, naturally, does not disclose its lists of clients, but there are sufficient management books, penned by its proud partners and extolling the wonders of the pre-implosion Enron, to know that the two were firm friends, if not identical twins.

According to The War for Talent, by Ed Michaels, Helen Handfield-Jones and Beth Axelrod (have we found ourselves a 'performance cell'?), 'From a stodgy gas pipeline firm, the company has evolved into a world-class risk-management player — parlaying those skills into a $55 billion empire.' Later on, the triumvirate eulogise: 'Few companies will be able to achieve the excitement extravaganza that Enron has in its remarkable business transformation. But many could apply some of its principles.'

The War for Talent is a McKinsey study about how to recruit and retain the top people without losing them to your worst enemy after six months. It was a mantra chanted by Enron. Ignoring the finer strategic intricacies of this McKinsey initiative, it seems to be a lot to do with a lot of money. One former Enron execu tive, quoted in another McKinsey masterpiece, Creative Destruction, explains, 'We hire very smart people and we pay them more than they think they are worth.'

The book celebrates the approach taken by Jeffrey Skifling, former chief executive of Enron and a McKinsey man for 11 years, towards young traders who were encouraged 'to commit up to $5 million on a deal without being obliged to seek upper-management approval'.

To keep such greatness, preaches The War for Talent, you have to hand over control of the steering wheel and leave a few signed blank cheques in the glove compartment. Presumably Skilling, who once said he felt as if he was 'doing God's work', had enough confidence to run his business trusting supremely in such spendthrift talent.

McKinsey, of course, has done a very good job of distancing itself from Enron, a strategy which it would surely have advised its own clients to do. Gupta has described himself as 'as much an observer of the kinds of activities that got Enron into trouble as you are'. 'We stand by all the work we did,' he insisted in a rare interview with Business Week. 'Beyond that, we can only empathise with the trouble they are going through. It's a sad thing to see.'

Enron is not the only cock-up among its clients. Swissair, K Mart and Global Crossing are three other companies which have not exactly satisfied McKinsey's mission statement (known in their language as Our Enduring Values) to 'being and delivering the best'. But McKinsey, quite rightly, would point out that it did very little work for some of these clients, while reciting one of its many catchphrases: we have worked for 400 clients for 15 years or more. Message to non-McKinsey person: Enron is one failure among several hundred successes.

Its largest client is said to have paid $60 million for its advice last year, but it is impossible to discover who the client is, or even if it is true, as McKinsey will hardly even confirm the spelling of its own name.

With 147 of the world's 200 largest corporations on its books, including 80 of the top 120 financial services firms, nine of the 11 largest chemical companies and 15 of the 22 biggest healthcare and pharmaceutical companies, it is easy to see why McKinsey thinks it is unfair to dwell on the Enron subject. Its clients are so big and so .. . well, everywhere that one Houston energy trader, formed in 1985 from the merger of two companies with names not chosen for the spotlight — Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth hardly dents its bumper.

Its clients are also diverse. It has even done work, free of charge, for the New York police and fire departments, compiling a report on the operational lessons which could be learnt from 11 September.

Enron's auditors, Arthur Andersen, some of whose staff proved themselves to be impressively proficient with a papershredder, may have collapsed, but McKinsey — far away from off-balance sheet transactions — stays clean. They manage to boast about an approach — We work with clients, not for them' — but put the distance between themselves when convenient.

One of the great gifts of the management consultancy industry is that it can advise companies while getting paid handsomely to do so but, like Macavity, not leave even a paw-print on the station platform if things go wrong. They are, after all, only advising the management of a company. The manager's decision is final.

McKinsey's survival from the Enron earthquake has left the management monolith at its biggest since it was founded by James 'Mac' McKinsey, a former University of Chicago accounting professor, in 1926. His first client? A meatpacker called Armour & Co.

The number of consultants has jumped from 2,900 in 1993 to 7,700, partners from 427 to 891, and clients from 900 to 1,700. Proving that McKinsey does not inhabit the same galaxy as others, not one consultant has been made redundant despite a rapid decline in its business levels since the irrational exuberance of 1999. Some administrative roles have been cut and its hunger for the annual round of MBA (Master of Business Administration) graduates has waned, but not one consultant has been chopped.

International offices have jumped from 58 to 84, introducing McKinsey-speak to Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Middle East. In London, it has two offices — one in Jermyn Street, one in Kensington Church Street (near the park, 'where colleagues often jog together after work'). Staff — who presumably have a much cleverer name than such a pedestrian title — do not just work for McKinsey. You are a McKinsey man or woman, just as you are a Pr& a Manger person or a Goldman Sachs groupie.

The website shows photographs of staff in various poses with cheesy captions underneath such as 'Sharing a laugh can be as important as sharing an idea' or 'Charts are worth a thousand words' or 'The phone is great for catching up with team mates. Or catching the game score.'

We must hope that they do, indeed, share a laugh, for at one point the comprehensive website exclaims, 'But we do understand that you have a life outside McKinsey.' This life outside McKinsey has done a lot to build up the myth surrounding the company. Once you start looking, the name does not stop cropping up, and that is not just William Hague's fault: not one but two directors of Marks & Spencer, the chairman of the Financial Services Authority, the former chairman of Asda, the chairman of the London Stock Exchange, even an assistant private secretary to the Queen.

Sir Howard Davies, who served a fiveyear stint between 1982 and 1987, starred in an article on the McKinsey News Network in March last year under the headline 'You can take it with you'. There are, it announced, 'gentle echoes of the Firm throughout the Financial Services Authority'. With such a fan club, no wonder McKinsey is considered to be — and, most importantly, considers itself to be indestructible.

Previous page

Previous page