Subsidising the arts

Tom Sutcliffe

The economic policies associated with the name of John Maynard Keynes are out of fashion in the West. Yet Keynes's belief in state subsidy of the arts has become the universal orthodoxy. Even the United States has acquired a federal programme of arts spending, and governments of the developed world — whether socialist or capitalist — feel as responsible for the condition of the national artistic culture as for the defence of the realm.

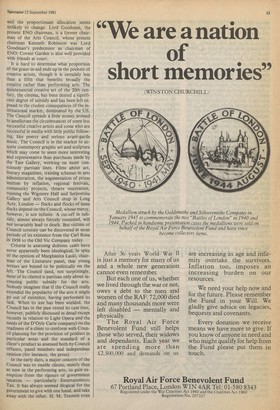

In pre-war and wartime Britain, Keynes was a pioneer of subsidy. From 1942 he was chairman of the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA). Had he lived, he would have been the founding chairman of the Arts Council. In July 1945 he broadcast to the nation the good news that CEMA 'with a new name and wider opportunities should be continued into time of peace'. 'State patronage of the arts has crept in . . .', he said. 'At last the public exchequer has recognised the support and encouragement of the civilising arts of life as a part of their duty . . . But we do not think of the Arts Council as a schoolmaster. Your enjoyment will be our first aim. We have but little money to spill, and it will be you yourselves who will by your patronage decide in the long run what you get . . . It is also our business to make London a great artistic metropolis, a place to visit and to wonder at.'

In Britain this was pioneering. Yet Keynes was importing principles that had long been accepted on the Continent, where monarchies and republics alike regarded the arts as a legitimate instrument for affirming national identity. In England, on the contrary, ever since the Glorious Revolution of 1688, governments had regarded royal or governmental patronage of the arts as an extravagance. Patriotism in England was commercial: it did not need to be artificially fostered, it could pay for itself.

Only under the patriotic stimulus of war could such a reversal of the traditional view in Britain have been achieved. Yet, how important it has been during this country's post-war decline for the middle-class ego to have the reassurance of a national arts policy! Lord Goodman underlined this recently when he launched an appeal for funds for the English National Opera. We might have lost an empire, said Lord Goodman, but we had gained an international reputation for the high quality of our arts.

The French have the Pompidou Centre. Britain has the National Theatre. These are characteristic prestige symbols of our time. The Royal Shakespeare Company, we can read in an Aldwych programme, 'has become one of the best known theatre companies in the world . . . one of the largest theatre companies in the world, regularly playing to audiences of more than one million in this country and abroad . . . audiences which we believe are equalled by no other company in the world.' Soon the Aldwych will be abandoned for the Barbican, another arts centre for London, this time funded generously by the City itself. Or perhaps Trevor Nunn's expanding company will keep the Aldwych as an additional theatre.

There was in Britain an isolated instance of arts subsidy before the creation of CEMA. In 1930 the Labour administration spent £17,500 helping the BBC to relay opera from Covent Garden. The same sum was provided in 1931, and a further £5,000 was spent in 1932 before the National government axed the scheme. It is significant that opera should have been the first beneficiary of subsidy in Britain. It is the ideal stalking horse for the proselytisers of state spending on the arts. Only rarely and in special instances, as in London in the 1720s, has opera been able to pay its way, in the sense of the box office meeting the costs of the enterprise. There is no opera house in the world today that does not depend on what Keynes called 'non-economic' donations, money paid by people for reasons other than to buy access to the product.

When helping to create Covent Garden as a national institution and metropolitan home of ballet and opera that could stand comparison with international equivalents in Vienna, Paris and Moscow, Keynes expected much of the cost to be born by the rich. But the tax arrangement that he anticipated as the engine for these private funds, and which remains the backbone of both the Met in New York and much other artistic enterprise in the US, was outlawed by Sir Stafford Cripps's first budget. (Attlee's administration also failed to make special terms with Calouste Gulbenkian that would have resulted in his collection finding a permanent home in London rather than in Lisbon, a comparable instance of inflexible egalitarianism.) Keynes would not have found healthy or desirable the present over-dependence of so many arts organisations on subsidy.

The main difference between state subsidy and contributions made partly at the expense of the national tax revenue by individuals or enterprises through special arrangements and allowances is that private 'non-economic' patronage (such as is usual in the US) is pluralist. If a variety of people pay the piper, a greater range of tunes is likely to be called.

In practice the dominance of institutions like the Royal Shakespeare and National companies may not be vastly different from the old system of capitalist entrepreneur. In place of `Binkie' Beaumont and the empire of H.M. Tennent, the theatre is now dominated by Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn. Private institutions, however, are more likely to be allowed to fade away than public institutions, which tend to be kept going long after their original character and true purpose have vanished.

The operations of the Arts Council (and its various offshoots, the local arts associations and the autonomous national bodies in Wales and Scotland) have been strikingly consistent since its foundation. Unlike the wartime ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association) with its low to middle brow obligation to boost morale by giving people a good time, CEMA's purposes were highbrow and potentially expensive. The Arts Council's charter of 1946 originally defined its purpose as 'developing a greater knowledge, understanding and practice of the fine arts exclusively, and in particular to increase the accessibility of the fine arts to the public . . ., to improve the standard of execution of the fine arts, and to advise and cooperate with government departments, local authorities and other bodies.' The reconstituted charter of 1967 omitted the word 'fine' in the phrase 'fine arts' and made no mention of the conservatorial commitment to 'improve the standard of execution.' The Arts Council has been a pressure group to increase state spending on the arts, and despite (or perhaps because of) its constant harping on the poverty of its resources it has been hugely successful.

The Arts Council of Great Britain, published by Davis-Poynter in 1975, is a detailed and approving description by Eric Walter White, assistant secretary of the Council from 1945 to 1971, of the growth in arts subsidy from £100,000 in 1942 to £28,850,000 in 1975-6. Six years later that figure has reached £80 million, reflecting the non-partisan acceptance by Conservative and Labour governments that arts spending should be inflation-proof. Yet the tradition of crying wolf about the shortfall in government generosity goes back a long way: the annual report published in 1957 was titled 'Art in the Red'. As a pressure group, the Arts Council is now highly sophisticated: scarcely a day passes without the mailing of some new press release, explaining details of subsidies small and large.

The percentage of the gross subsidy going to a particular art form has changed hugely over the years, as has the percentage spent on metropolitan activities. In 1959-60 55.25 per cent of the Arts Council grant-in-aid went to Covent Garden and Sadler's Wells Opera (now ENO). In the last financial year that percentage was down to 18.54, approximately the same as it has been since 1972-73. This reflects the global increase in subsidy, not a fierce reduction in real terms of spending on opera (and ballet). Actually London is generously treated by the Arts Council as far as opera goes, getting 56 per cent of the £16 million opera subsidy in Britain in the current year, which represents 221/2 per cent of the current grant-in-aid, and the proportionate allocation seems unlikely to change. Lord Goodman, the present ENO chairman, is a former chairman of the Arts Council, whose present chairman Kenneth Robinson was Lord Goodman's predecessor as chairman of ENO; Covent Garden is also well provided with friends at court.

It is hard to determine what proportion of the grant-in-aid ends up in the pockets of creative artists, though it is certainly less than a fifth that benefits broadly the creative rather than performing arts. The quintessential creative art of the 20th century, the cinema, has been denied a significant degree of subsidy and has been left exposed to the crudest consequences of the international market, dominated by the US. The Council spreads a little money around to ameliorate the circumstances of some less successful creative artists and some who are successful in media with little public following, like poetry and serious avant-garde music. The Council is in the market to acquire contempory graphic art and sculpture Which may come to seem more interesting and representative than purchases made by the Tate Gallery, working on more consciously partisan lines. Films about art, literary magazines, training schemes in arts administration, the augmentation of prizes smitten by inflation, regional festivals, community projects, theatre restoration, running the Wigmore Hall and Serpentine Gallery and Arts Council shop in Long Acre, London — flocks and flocks of lame ducks depend on the Council, whose mercy, however, is not infinite. A cut-off in subsidy, almost always fiercely contested, will not invariably lead to death. But victims of Council scrutiny can be discovered at most periods of its existence from the Carl Rosa in 1958 to the Old Vic Company today.

Criteria in assessing dubious cases have never apparently been ideological, in spite of the opinion of Marghanita Laski, chairman of the Literature panel, that young writers are bound to be politically on the left. The Council (and, not surprisingly, most of its clients) is partisan only about increasing public subsidy for the arts. Nobody imagines that if the Council really extended the popularity of the arts it might go out of existence, having performed its task. When its axe has been wielded, the Council has in the past rested its case (not, however, publicly discussed in detail except recently in relation to Light Opera and the needs of the D'Oyly Carte company) on the readiness of a client to conform with Council planning for the provision of product in particular areas and the standard of a Client's product as assessed both by Council officers, panel members and independent Opinion (for instance, the press).

In the early days, a major concern of the Council was to enable clients, mostly then as now in the performing arts, to gain exemption from the rigours of government taxation — particularly Entertainments Tax. It has always seemed illogical for the government to give with one hand, and take away with the other. H. M. Tennent even went so far as to establish 'charitable' subsidiaries both to avoid Entertainments Tax and to be eligible for guarantees from the Council against loss, guarantees which were scarcely at all needed. This anomaly, which disappeared with the abolition of Entertainments Tax, was revived by the introduction of VAT. But it was argued if some arts institutions were tax exempt it would be highly controversial and divisive; it would also be unfair to impresarios like Michael Codron and the Alberys, already labouring under terms of trade loaded against them.

The Arts Council is designed as an elitist organisation. Both the institutions and the activities it supports are by nature refined (the abandonment of the word 'fine' in the charter could not change that) and cater for specialised tastes. The admission by the present secretary general, Sir Roy Shaw (formerly an adult educationist by profession), that at most the Arts Council brings benefit to only 10 per cent of the population could be claimed as an achievement, compared with how much worse the appreciation of the arts would be without its efforts.

It is worth questioning the Council's predominantly conservationist approach. The Arts Council gives some areas of cultural life highly favourable treatment. Others are denied such support. The performing arts which the Council fosters are predominantly a middle-class, minority taste, in itself perfectly inoffensive. They have become uneconomic and in need of subsidy mainly because of technological and social changes. And they have become even more uneconomic because of the early commitment by the Council to depress the level of ticket prices both to stimulate demand and to increase accessibility for the worse-off. The squeezing of income differentials has meant that fewer people have been prepared to pay a realistic price for such specialised entertainments and also arts workers achieved substantially increased financial rewards. Furthermore the newly mechanised means of reproduction, as embodied in the film and record industries, radio and television, have completely transformed the market for music and drama (whether highor low-brow). This process is still going on.

By making uneconomic activities more attractive and secure, the Arts Council has (as indeed was intended) interfered both with a process of decline and with the development of the natural replacement. How much has the British film industry lost potential producers of talent, to the booming new breed of artistic administrators? Have the severe restrictions placed by successive governments on the development of the wonderful British television system guaranteed its quality or prevented it from being a great deal better? There are many hidden penalties for seeing certain kinds of art as being specially deserving of an easy time, and perhaps the late 20th century — with its twin elitist obsessions of conservation and avant-garde originality — is particularly unsuited to the operation of an official subsidised system. That nonideological commitment, which seems so virtuous and reasonable, may turn out to be particularly debilitating.

Previous page

Previous page