BOOKS

Beyond the Misty Mountains

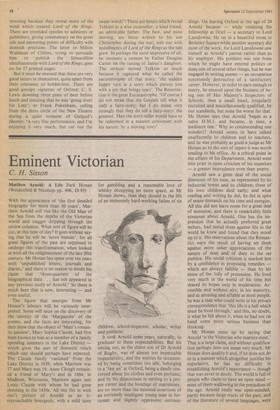

A. N. Wilson The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: A selection ed. Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien (Allen and Unwin pp. 463, £9.95) J. R. R. Tolkien's genius was all of a piece. In his academic career and in his personal life and in his art, he was the same man. This sounds like a platitude, but it is in fact highly unusual. Eminent scholars are, more often than not, bored with their 'subjects. And there is often so complete a division between the 'writing persona' and the 'real self' of an author that the task of biography becomes necessarily offensive. None of this applies to Tolkien. That is what gives his mythologies their power. Plenty of people have disliked them, or been jealous of their commercial success; but no one, with Justice, could ever have thought them whimsical or posing. They sprang naturally out of his apprehension of the real world, • as we can now perceive by reading this remarkable selection of letters.

Perhaps his first and greatest love was Language, for its own sake. He speaks, in a letter to W. H. Auden, of 'the acute pleasure derived from a language for its own sake, not only free from being useful but free even from being the "vehicle of a literature" '. That was why he loved Gothic, which has no literature. And so it was as a child that he gazed with fascination at coal-trucks on the railway line in Birmingham, labelled with Welsh names. It was as if the words alone had the power to transport him to a different time and plane; just as in old age, during a seaside holiday he enjoys the very names of Sidmouth shopkeepers 'such as Frisby, Trump and Potbury'.

In many obvious senses he was not at home in the modern, materialist world. When he writes with frustration of living at 99, Holywell (in Oxford) he is speaking of more than noisy traffic: 'This charming house has become uninhabitable — unsleepable-in, unworkable-in, rocked, racked with noise, and drenched with fumes. Such is modern life. Mordor in our midst'. But not merely did he feel displaced in 'this polluted country of which a growing proportion of the inhabitants are maniacs'. In the human body itself, he felt a stranger. After an unpleasant session with a doctor in old age he wrote to his son, 'We (or at least I) know far too little about the complicated machine we inhabit'.

With good Augustinian, not to say Platonic, precedent, Tolkien's sense of the present world's futility, folly and unreality stemmed from his lively faith in a world beyond: and this other world was, prim arily, the Heaven of conventional Catholicism. So, to his 'son Christopher, posted to South Africa during the war, he can write, 'Remember your guardian angel. Not a plump lady with swan-wings! . . . But God is . . . behind us, supporting, nourishing us (as being creatures). The bright point of power where that life-line, that spiritual umbilical cord touches: there is our Angel, facing two ways, to God behind us in the direction we cannot see, and to us' . . . .

When, years later, this umbilical cord was loosed and his correspondent lost a sense of this other world, it was an enor mous grief to Tolkien: 'When I think of my mother's death . . . worn out with persecu tion, poverty, and largely consequent, disease, in the effort to hand on to us small boys the Faith, and remember the tiny bedroom she shared with us in rented rooms in a postman's cottage at Rednal, where she died alone, too ill for viaticum, I find it very hard and bitter when my children stray away from the Church'. In the same letter he writes, 'in hac urbe lux solemnis has seemed to me steadily true'.

Yet its truth was best apprehended, in his distinctive imagination, when transformed into story and mythology. His love of language suggested much of the myth's substance. In the case of the 'ents', for ex ample, the majestic walking trees of his story, 'as usually with me they grew rather out of their name than the other way about.

I always felt that something ought to be done about the peculiar Anglo-Saxon word ent for a "giant" or a mighty person of long ago — to whom all old works are ascribed'. He was not content to leave the ents as they appear on the page of Beowulf, shadowy, unknown figures of an almost forgotten past. A natural story-teller, Tolkien invested them with shapes, voices and habits of his own creation. Many of his fellow-mediaevalists have found The Lord of the Rings perpetually irritating for this reason. Any student of Anglo-Saxon knows that an ent is not a walking tree: it is some sort of giant, perhaps a nickname for the Romans. But in the imaginations of the millions, in their Gandalf T-shirts, the ent has taken leave of its Anglo-Saxon origins and become something other. So the dons would argue; and they could choose countless other examples of names from the Edda, or mediaeval Welsh or from AngloSaxon verse and riddles where Tolkien took up an old name and transformed it for his own story-telling purposes.

The objectors fail to recognise the wholeness of Tolkien's imaginative sweep. The tales were not one part of his life, written in 'time off' from academic or family pursuits. They are an expression of his whole experience of life. This is what the Letters make so fascinatingly clear. At the beginning, in an undergraduate letter to his future wife, he reports that he has 'done some touches to my nonsense fairy language'; but the importance of this invented grammar had not yet dawned on him; he can still apologise for it as 'such a mad hobby'. Almost no letters of the intervening 20 years are included in this volume; perhaps they do not exist; perhaps they are too personal for publication. But by the late 1930s, when Tolkien had returned to Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor, all the strands of his life had become enmeshed in their inevitable pattern: the love of philology; the sense of the Church as the one city in which lux solemnis shines on in a dark world; the zest for story-telling; the poignant and increasingly strong sense that 'Men are essentially mortal and must not try to become "immortal" in the Flesh'. Thus the divisions between his imagined world and the world of all of us grow shadowy. 'I am historically minded', he protests to one correspondent, 'Middle Earth is not an imaginary world . . . The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live'. This is not whimsy. The letters reveal innumerable glimpses of how it was, in his bwn life, literally true. This is particularly true of the letters written in old age. To a son who has enjoyed a holiday in Switzerland he writes, 'The hobbit's [Bilbo's] journey from Rivendell to the other side of the Misty Mountains, including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods, is based on my adventures in 1911'. To another son, he writes more solemnly on the subject of his wife's gravestone, inscribed simply with her name and the word Ltithien. !I never called Edith Ltithien, but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks at Roos in Yorkshire (where I was for a brief time in command of the Humber Garrison in 1917, and she was able to live with me for a while). In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing — and dance. But the story has gone crooked & I am left, and I cannot plead before the inexorable Mandos': None of the letters show more movingly how much his inner mythologising and his outer story-telling were at one. The reader begins to see why he protested to R. W. Burchfield, the reviser of the Oxford English Dictionary, against his etymology of the word hobbit: 'invented by J. R. R. Tolkien'. He Was not sure that the word had been invented. It was almost no surprise in 1956 when he received a letter from a 'real person' called Mr Sam Gamgee, of Tooting. 'He could not have chosen a more Hobbit-sounding place, could he? — though unShirelike, I fear, in reality'.

These letters, then, are primarily in teresting because they reveal more of the mind which created Lord of the Rings. There are extended epistles to admirers or publishers, giving commentary on the great tale and answering points of difficulty with donnish precision. The letter to Milton Waldman of Collins, trying to persuade him to publish the Sihnarillion simultaneously with Lord of the Rings, goes on for 17 printed pages.

But it must be stressed that these are very good letters in themselves, quite apart from their relevance to hobbit-lore. There are good gossipy vignettes of Oxford: C. S. Lewis downing three pints of beer before lunch and insisting that he was 'going short for Lent'; or Frank Pakenham, yelling from the dress circle of the New Theatre during a quiet moment of Gielgud's Hamlet, 'A very fine performance, and I'm enjoying it very much, but cut out the swear-words'! There are letters which reveal Tolkien as a wise counsellor, a kind friend, an admirable father. The best, and most moving, are those written to his son Christopher during the war, sent out with installments of Lord of the Rings as the tale grew. In perhaps the most impressive of all, he recounts a sermon by Father Douglas Carter on the raising of Jairus's daughter. The sermon moved Tolkien so much because it captured what he called the eucatastrophe of that story: 'the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears'. The Resurrection is the great Eucatastrophe. 'Of course I do not mean that the Gospels tell what is only a fairy-story; but I do mean very strongly that they do tell a fairy-story: the greatest. Man the story-teller would have to be redeemed in a manner consonant with his nature: by a moving story'.

Previous page

Previous page