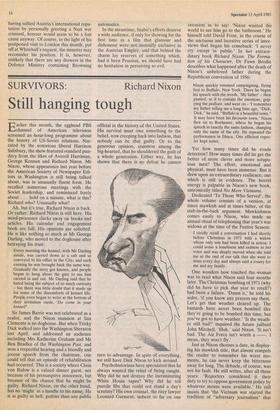

Still hanging tough

Earlier this month, the egghead PBS channel of American television screened an .hour-long programme about the history of US-Soviet relations. Nar- rated by the notorious liberal Harrison Salisbury, the show featured standard pun- ditry from the likes of Averell Harriman, George Kennan and Richard Nixon. Mr Nixon, whose appearance last year before the American Society of Newspaper Edi- tors in Washington is still being talked about, was in unusually fluent form. He recalled numerous meetings with the Soviet leadership, and reminisced freely about . . . hold on a minute, what is this? Richard who? Unusually what?

Ah, but it's true. Richard Nixon is back. Or rather, Richard Nixon is still here. His word-processor clacks away on books and articles. His calendar and engagement book are full. His opinions are solicited. He is like nothing so much as Mr George Darling, who moved to the doghouse after betraying his trust:

Every morning the kennel, with Mr Darling inside, was carried down to a cab and so conveyed to his office in the City; and each evening he was brought back the same way. Gradually the story got known, and people began to hang about the gate to see him carried in and out. Mr Darling said that he hated being the subject of so much curiosity — but there was little doubt that it made up for some of the discomforts of kennel life. People even began to write at the bottom of their invitation cards, 'Do come in your kennel!'

Sir James Barrie was not celebrated as a realist, and the Nixon mansion at San Clemente is no doghouse. But when Tricky Dick walked into the Washington Sheraton last April, and addressed an audience including Mrs Katherine Graham and Mr Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post, and won a respectful hearing and a friendly and jocose speech from the chairman, one could tell that an episode of rehabilitation had occurred. This is a society where Claus von Bulow is a valued dinner guest, not because of his presumptive innocence, but because of the chance that he might be guilty. Richard Nixon, on the other hand, has no 'might' as a handle to his name. He is as guilty as hell; guiltier than any public

official in the history of the United States. His survival must owe something to the belief, now creeping back into fashion, that nobody can be that guilty. Or to the generous opinion, common among the big-hearted, that he shouldered the guilt of a whole generation. Either way, he has shown that there is no defeat he cannot turn to advantage. In spite of everything, we still have Dick Nixon to kick around.

Psychohistorians have speculated that he always wanted the relief of being caught. Why did he not destroy the incriminating White House tapes? Why did he tell puerile fibs that could not stand a day's scrutiny? His own counsel, the ritzy lawyer Leonard Garment, unbent so far on one

occasion as to say: 'Nixon wanted the world to see him go to the bathroom.' He himself told David Frost, in the course of the unctuous and lucrative series of inter- views that began his comeback: 'I never cry except in public.' In her extraor- dinary book Richard Nixon: The Forma- tion of his Character, Dr Fawn Brodie describes what happened after the death of Nixon's unbeloved father during the Republican convention of 1956:

Nixon quickly resumed campaigning, flying first to Buffalo, New York. There he began his speech with the words, 'My father' — then paused, as if to contain the emotions, grip- ping the podium, and went on — 'I remember my father telling me a long time ago, "Dick, Dick," he said, "Buffalo is a beautiful town." It may have been his favourite town.' Nixon flew on to Rochester, where he began his speech in exactly the same fashion, changing only the name of the city. He repeated the performance in Ithaca. One efficient repor- ter kept notes.

Yet how many times did he evade detection? How many times did he get the better of more clever and more scrupu- lous men? The effort, emotional and physical, must have been immense. But it drew upon an extraordinary resilience; one which is still in evidence. The horrid energy is palpable in Nixon's new book, unironically titled No More Vietnams.

Dedicated To Those Who Served', the whole volume consists of a version, at times mawkish and at times bitter, of the stab-in-the-back argument. Mawkishness comes easily to Nixon, who made an annual ritual of telephoning that year's war widows at the time of the Festive Season:

I vividly recall a conversation I had shortly before Christmas in 1971 with a widow whose only son had been killed in action. I could sense a loneliness and sadness in her voice and was deeply moved when she told me at the end of our talk that she went to mass every day and always said a rosary for me and my family.

One wonders how touched the woman was to read what Nixon said four months later. The Christmas bombing of 1971 (why did he have to pick that year to retell?) had been a failure. 'Damn it,' he told his aides, If you know any prayers say them. Let's get that weather cleared up. The bastards have never been bombed like they're going to be bombed this time, but you've got to have weather.' Is the weath- er still bad?' inquired the future jailbird John Mitchell. 'Huh,' said Nixon. 'It isn't bad. The Air Force isn't worth a —. I mean, they won't fly.'

Just as Nixon chooses a date, in display- ing his mawkish side, that almost compels the reader to remember his worst mo-. ments, he can never keep the bitterness away for long. The debacle, of course, was not his fault. He still writes, after all these years: 'Reporters considered it their duty to try to oppose government policy by whatever means were available.' He still insists that 'the Vietnam war started the tradition of "adversary journalism" that

still poisons our national life today.' And he still maintains, in a revealing choice of phrase, that we inhabit 'a world where good manners are potentially fatal hind- erances.'

Well, whatever undid Nixon it was not an excess of nicety on his part. He has still to offer either an apology or an explana- tion for the events that took him to the doghouse in California and to the numer- ous other houses which a grateful taxpayer Still subsidises through his lavish ex- Presidential pension. He has yet to show any sign of grace about his pardon, or any gesture of magnanimity towards those whom he slandered and persecuted when in office. But it is precisely this want of remorse or shame that gives him his durability. Apology be damned. The man is still hoping for vindication.

And he may live to see it. Ronald Reagan's triumph in 1980 was described by the leading neo-conservative Norman Podhoretz as 'the election that Watergate postponed'. The Reaganites believe that, at least in foreign policy, Nixon blazed some valuable trails. His opening to China and his hard line with Chile are both recalled with affection. Paradoxically if there is a rapprochement with the Soviet Union, the Nixon of détente will be able to claim prescience in that respect also. His old speechwriter Pat Buchanan, a veteran Press-hater and liberal-baiter, has just been hired as White House Director of Communications. His nostrums about the enemy within are the small change of Administration talk.

Roy Cohn, chief aide to Senator Joe McCarthy, once said disgustedly of Nixon that he 'was perfectly willing to turn on his Conservative friends and cut their throats – one, two, three.' An Oval Office subordin- ate commented half admiringly, 'For Dick, the shortest distance between two Points is over four corpses.' In a country where celebrity and notoriety are such Close cousins, a reputation for ruthlessness and treachery is not an absolute handicap. A reputation for 'hanging tough', on the other hand, is invaluable. The other mem- bers of the Nixon gang have all made amends of a sort – either retiring complete- ly from view or making ostentatious con- version to Christianity and good works. The chief alone continues, with the same scowling determination, to pursue a des- tiny. It may be that he can do no other. But there is a relish in his pursuit of the old vendettas, and such a readiness to court Still more exposure and ridicule that one must wonder. As Mrs Darling said to her husband:

'You are still awfully sorry about it, aren't you? You're still full of remorse, aren't you?' It took him by surprise. 'Full of . . . ? Sorry . . . ?'he stuttered. 'My dear, look at me! See how I continue to live in Nana's kennel, to punish myself — and very cramping it is, my dear.'

'Yes,' said his wife, sticking to her point, 'but you are sure you are not — enjoying it, rather?'

Previous page

Previous page