The Great Happiness, the paradise we come from

Giles Auty

CECIL COLLINS: THE QUEST FOR THE GREAT HAPPINESS by William Anderson

Barrie & Jenkins, f25, pp. 192

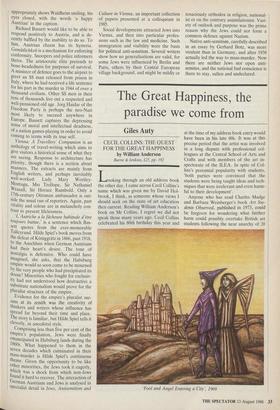

Looking through an old address book the other day, I came across Cecil Collins's name which was given me by David Hol- brook, I think, as someone whose views I should seek on the state of art education then current. Reading William Anderson's book on Mr Collins, I regret we did not speak those many years ago. Cecil Collins celebrated his 80th birthday this year and at the time of my address book entry would have been in his late 60s. It was at this precise period that the artist was involved in a long dispute with professional col- leagues at the Central School of Arts and Crafts and with members of the art in- spectorate of the ILEA. In spite of Col- lins's perennial popularity with students, `both parties were convinced that the students were being taught ideas and tech- niques that were irrelevant and even harm- ful to their development'. • Anyone who has read Charles Madge and Barbara Weinberger's book Art Stu- dents Observed, published in 1973, could be forgiven for wondering what further harm could possibly overtake British art students following the near anarchy of 20 `Fool and Angel Entering a City', 1969 years ago. Collins's methods appear to have been singular certainly, and he de- scribes his teaching as empathetic know- ledge as opposed to analytical knowledge: 'I see all creation as a dance . . . and my teaching is based on the dance too. I see the drawing as a dance and, as it were, the paper over which the instrument moves. I have always been very moved by ritualised gesture, archetypal gesture. In a way a lot of my teaching and, most certainly, my paintings are rites.'

Cecil Collins is a visonary whose work treats of the inner realities of the soul. As the jacket of the book explains: 'His central theme is the Great Happiness, the paradise we come from, for which we always yearn in our innermost being, and which is restored to us through the creative imagination.' It strikes me that contem- platives might argue that the practice of art is, if anything, an unnecessary distraction from the paths of inner discovery. Because the mystical artist accepts responsibility to no order but his own, he is in danger of investing himself with ultimate moral and aesthetic authority and becoming a self- appointed guru. Critics are placed in the uncomfortable role of accepting all or nothing and so, too, are biographers. The author, who is a poet primarily, is a discerning disciple, yet disciple never- theless. The metaphysical imagination is a complex subject which Mr Anderson tackles with sensitivity and courage. He uses clarity of language rather than simplifi- cation of issues to build a bridge to his readers. Such writing serves not only to make it abundantly clear why Collins does not belong, as an artist, with bodies such as the Surrealists or neo-Romantics but also defines his differences from other individualistic British artists who had mys- tical inclinations: Eric Gill, for instance, and David Jones.

Cecil Collins was born in Plymouth in 1908 and spent long stretches of his child- hood in Cornwall, a county never short of magical influence. There the landscape enfolds myth and legend no less than hill forts or other marks of an ancient past. These latter, and a grounding in the Bible, sank early into this imaginative child's consciousness. His studies at Plymouth School of Art and the Royal College, passed happily: 'For Collins this academic training was not at all the debilitating and sapping regime it was made out to be when so many art schools did away with such courses in the Sixties and Seventies.'

Collins suffered ill-health from child- hood but was fortunate in his choice of wife and in the enthusiastic help supplied by patrons and advisers. I intend no disrespect in saying that biographies of artists would seem more real and exemplary if they told us a little more about the everyday cir- cumstances of their subjects' lives. Even dreamers and visionaries need to eat.

The book has 122 illustrations, of which 52 are in colour.

Previous page

Previous page