SPE THE

The Spectator, 56 Doughty Street, London WC1N 2LL Telephone: 0171-405 1706; Fax 0171-242 0603

THE BRANSON OF OUR TIME

Al politicians strive to personify the product, to become the brand. Tony Blair is New Labour, and although his party could form a government without him, it would be a very different product. Reducing a complex mix of people and policies to a sin- gle, person makes it much easier to commu- nicate with the electorate. The Prime Min- ister's repeated requests for the electorate to put their trust in him reinforces his mes- sage that 'I am the brand'.

Businesses use the same technique. The recent appearance on television of Sir Peter Davis, chief executive of Prudential, as 'the man from the Pru', demonstrates that even this normally cautious insurance company recognises the power of personality. But the supreme practitioner of the tactic is Richard Branson.

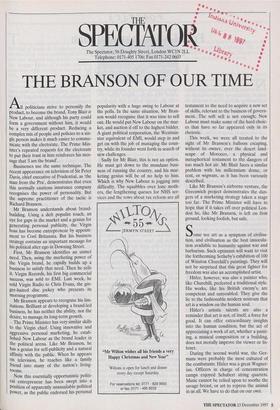

Mr Branson understands about brand- building. Using a deft populist touch, an eye for gaps in the market and a genius for generating personal publicity, the Virgin boss has become entrepreneur by appoint- ment to Cool Britannia. But his business strategy contains an important message for his political alter ego in Downing Street.

First, Mr Branson identifies an unmet need. Then, using the marketing power of the Virgin brand, he rapidly builds up a business to satisfy that need. Then he sells it. Virgin Records, his first big commercial success, was sold to EMI. Last week, he sold Virgin Radio to Chris Evans, the gin- ger-haired disc jockey who presents its morning programme. . Mr Branson appears to recognise his lim- itations. Brilliant at developing a brand-led business, he has neither the ability, nor the desire, to manage its long-term growth.

The Prime Minister has very similar skills to the Virgin chief. Using innovative and aggressive personal marketing, he estab- lished New Labour as the brand leader in the political arena. Like Mr Branson, he has a genius for self-publicity and a natural affinity with the public. When he appears on television, he reaches like a family friend into many of the nation's living- rooms.

Now this essentially opportunistic politi- cal entrepreneur has been swept into a Position of apparently unassailable political Power, as the public endorsed his personal popularity with a huge swing to Labour at the polls. In the same situation, Mr Bran- son would recognise that it was time to sell out. He would put New Labour on the mar- ket, and auction if off to the highest bidder. A giant political corporation, the Westmin- ster equivalent of EMI, would step in and get on with the job of managing the coun- try, while its founder went forth in search of new challenges.

Sadly for Mr Blair, this is not an option. He must get down to the mundane busi- ness of running the country, and his mar- keting genius will be of no help to him. Which is why New Labour is jogging into difficulty. The squabbles over lone moth- ers, the lengthening queues for NHS ser- vices and the rows about tax reform are all testament to the need to acquire a new set of skills, relevant to the business of govern- ment. The soft sell is not enough; New Labour must make some of the hard choic- es that have so far appeared only in its rhetoric.

This week, we were all treated to the sight of Mr Branson's balloon escaping, without its owner, over the desert land- scape of Morocco, a physical and metaphorical testament to the dangers of too much hot air. Mr Blair faces a similar problem with his millennium dome, or tent, or wigwam, as it has been variously described.

Like Mr Branson's airborne venture, the Greenwich project demonstrates the dan- gers of a marketing strategy taken a stage too far. The Prime Minister will have to hope that if it takes off over political Lon- don he, like Mr Branson, is left on firm ground, looking foolish, but safe.

Some see art as a symptom of civilisa- tion, and civilisation as the best innocula- tion available to humanity against war and barbarism. Such optimists will want to visit the forthcoming Sotheby's exhibition of 100 of Winston Churchill's paintings. They will not be surprised that this great fighter for freedom was also an accomplished artist.

Hitler, however, was also a painter who, like Churchill, preferred a traditional style. His works, like his British enemy's, are competent and untroubled. They give the lie to the fashionable modern nostrum that art is a window on the human soul.

Hitler's artistic talents are also a reminder that art is not, of itself, a force for good. It can offer extraordinary insights into the human condition, but the act of appreciating a work of art, whether a paint- ing, a musical composition or a building, does not morally improve the viewer or lis- tener.

During the second world war, the Ger- mans were probably the most cultured of the combatants. Hitler was a great Wagner- ian. Officers in charge of concentration camps enjoyed Schubert string quartets. Music cannot be relied upon to soothe the savage breast, or art to repress the animal in us all. We have to do that on our own.

Previous page

Previous page