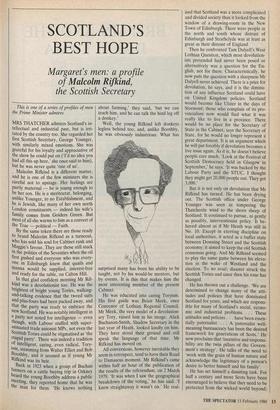

SCOTLAND'S BEST HOPE

Margaret's men: a profile

of Malcolm Rifkind,

the Scottish Secretary

This is one of a series of profiles of men the Prime Minister admires.

MRS THATCHER admires Scotland's in- tellectual and industrial past, but is irri- tated by the country too. She regarded her first Scottish Secretary, George Younger, with similarly mixed emotions. She was grateful for his loyalty and appreciative of the show he could put on (`I'd no idea you had all this up here,' she once said to him), but he was never quite 'one of us'.

Malcolm Rifkind is a different matter, and he is one of the few ministers she is careful not to upstage. Her feelings are partly maternal — he is young enough to be her son. He is a meritocrat, belonging; unlike Younger, to no Establishment, and he is Jewish, like many of her own north London constituents — indeed his wife's family comes from Golders Green. But most of all she warms to him as a convert of the True — political — Faith. By the same token there are those ready to brand Malcolm Rifkind as a turncoat, who has sold his soul for Cabinet rank and Maggie's favour. They are those still stuck in the politics of the Seventies when the oil first gushed and everyone who was every- one in Edinburgh knew that quails and manna would be supplied, interest-free and ready for the table, on Calton Hill. In that glad confident morning Mr Rif- kind was a devolutionist too. He was the brightest of bright young Tories, walking- and-talking evidence that the tweed suits and plus-fours had been packed away, and that the party was ready to embrace the new Scotland. He was notably intelligent in a party not noted for intelligence — even though, with Labour stuffed with super- annuated trade unionist MPs, not even the Scottish Tories could be stigmatised as 'the stupid party'. There was indeed a tradition of intelligent, caring, even radical, Tory- ism, stemming from Walter Elliot and Bob Boothby, and it seemed as if young Mr Rifkind was its heir.

Back in 1923 when a group of Buchan farmers on a cattle buying trip in Orkney heard the young Boothby address a public meeting, they reported home that he was the man for them. 'He knows nothing about farming,' they said, tut we can teach him, and he can talk the hind leg off a donkey.'

Well, the young Rifkind left donkeys legless behind too, and, unlike Boothby, he was obviously industrious. What has surprised many has been his ability to be taught, not by his would-be mentors, but by events. It is this that makes him the most interesting member of the present Cabinet.

He was educated into caring Toryism. His first guide was Brian Meek, once Convenor of Lothian Regional Council. Mr Meek, the very model of a devolution- ary Tory, raised him in his image. Alick Buchanan-Smith, Shadow Secretary in the last year of Heath, looked kindly on him. They have stood their ground and still speak the language of that time. Mr Rifkind has moved on.

All conversions, however inevitable they seem in retrospect, tend to have their Road to Damascus moment. Mr Rifkind's came within half an hour of the publication of the results of the referendum, on 2 March 1979. `It was when I saw the geographical breakdown of the voting,' he has said. 'I knew straightaway it wasn't on.' He real- ised that Scotland was a more complicated and divided society than it looked from the window of a drawing-room in the New Town of Edinburgh. There were people in the north and south whose distrust of Edinburgh and Strathclyde was at least as great as their distrust of England.

Then he confronted Tam Dalyell's West Lothian Question, which most devolution- ists pretended had never been posed or alternatively was a question for the En- glish, not for them. Characteristically, he now puts the question with a sharpness Mr Dalyell never achieved. There is a price for devolution, he says, and it is the diminu- tion of any influence Scotland could have on United Kingdom policies. Scotland would become like Ulster in the days of Stormont; those who complain of its pro- vincialism now would find what it was really like to live in a province. There would be no place for the Secretary of State in the Cabinet, says the Secretary of State, for he would no longer represent a great department. It is an argument which he will put forcibly if devolution becomes a live issue again. As it is, he doesn't believe people care much. 'Look at. the Festival of Scottish Democracy held in Glasgow in September,' he says. 'It was backed by the Labour Party and the STUC. I thought they might get 20,000 people out. They got 3,000.'

But it is not only on devolution that Mr Rifkind has turned. He has been drying out. The Scottish office under George Younger was seen as tempering the Thatcherite wind to the shorn sheep of Scotland. It continued to pursue, as gently as possibly, interventionist policy. It be- haved almost as if Mr Heath was still in No. 10. Except in exerting discipline on local authorities, it acted as a buffer state between Downing Street and the Scottish economy; it aimed to keep the old Scottish consensus going. And Mr Rifkind seemed to play the same game between his eleva- tion in the wake of Westland and the election. To no avail; disaster struck the Scottish Tories and since then his tone has changed.

He has thrown out a challenge. `We are determined to change many of the atti- tudes and policies that have dominated Scotland for years, and which are respons- ible for many of Scotland's social, econo- mic and industrial problems. . . . These attitudes and policies . . . have been essen- tially paternalist. . . . A paternalist well- meaning bureaucracy has been the desired framework for generations of Scots.' He now proclaims that 'incentive and responsi- bility are the twin pillars of the Govern- ment's strategy'. He talks of the need to `work with the grain of human nature and acknowledge the legitimacy of a person's desire to better himself and his family'.

He has set himself a daunting task. For half a century and more Scots have been encouraged to believe that they need to be protected from the wicked world beyond; if Malcolm Rifkind had his way, the world would again feel it needed to be protected from the Scots.

The task is daunting for another reason. Scots have been persuaded, or have per- suaded themselves, that Thatcherism is an alien philosophy. As the representative in Scotland of a government which has been rejected by the Scottish electorate, he cannot avoid being seen as a sort of colonial governor. He knows that only success in changing attitudes can alter this, and takes encouragement from the grow- ing number of house-owners in Scotland, where house-ownership has traditionally been lower than in England, and from the fact that the majority of house-owners voted Conservative even in 1987. But he knows that there is an intellectual battle to be won; he has the intelligence and power of persuasion to do so.

It is a battle for his own future too. The Scottish Office is not necessarily a dead end (though it has often seemed so), but a further drop in the Tory vote in Scotland might cost Malcolm Rifkind not only his own seat, but his political career too. He made a success of his term as a junior minister in the Foreign Office — he has all the intuitive gifts that diplomacy requires, as well as the ability to master a brief thoroughly — and he would be a natural candidate for the Foreign Secretaryship if he makes a success of Scotland.

Unlike many very clever men, Malcolm Rifkind inspires affection too. (One Nationalist said recently that her glee at the succession of Tory defeats on election night was mixed with her anxious hopes that 'Malcolm would survive'.) He has a bubbling enthusiasm that is very attractive, and he is apparently quite without the pomposity and vanity which afflict so many politicians. Indeed he remains refreshingly spontaneous, natural and unaffected in conversation. He gives the impression of not taking himself with the utmost serious- ness, and his favourite poet is Pope.

He can look on himself with some detachment and has the Jewish love of irony. (It is a tribute to the essential decency of Scottish life that nothing has been made of his being Jewish. He will tell you, laughing, that when he and Michael Ancram were both candidates for a Tory nomination in the Borders, his Jewishness was no handicap, while Ancram's Catholic- ism was. At one coffee morning in Melrose a lady did seek confirmation that he was Jewish, only to say, 'I don't think there are many synagogues in the Borders.') As Margaret's man in Scotland, he may be seen to dance on a tightrope; it would be a loss for everybody if he fell off. But, though a loyal member of her team, he has too much character to be merely anyone's man. If anyone can persuade the Scots that Thatcherism has its origins in the Scottish Englightenment, it will be Malcolm Rif- kind. He is not the last hope for Scotland, but just now he is the best.

Previous page

Previous page