ARTS

Exhibitions

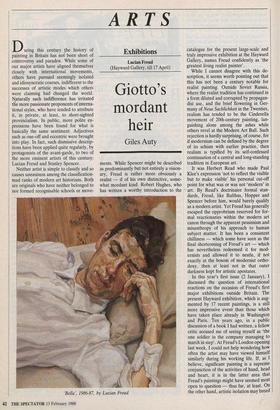

Lucian Freud (Hayward Gallery, till 17 April)

Giotto's mordant heir

Giles Auty

During this century the history of painting in Britain has not been short of controversy and paradox. While some of our major artists have aligned themselves closely with international movements, others have pursued seemingly isolated and idiosyncratic courses, indifferent to the successes of artistic modes which others were claiming had changed the world. /*katurally such indifference has irritated the more passionate proponents of interna- tional styles, who have tended to attribute it, in private, at least, to short-sighted provincialism. In public, more polite ex- pressions have been found for what is basically the same sentiment. Adjectives such as one-off and eccentric were brought into play. In fact, such dismissive descrip- tions have been applied quite regularly, by protagonists of the avant-garde, to two of the more eminent artists of this century: Lucian Freud and Stanley Spencer.

Neither artist is simple to classify and so causes uneasiness among the classification- mad ranks of modern art historians. Both are originals who have neither belonged to nor formed recognisable schools or move- ments. While Spencer might be described as predominantly but not entirely a vision- ary, Freud is rather more obviously a realist — if of his own distinctive, some- what mordant kind. Robert Hughes, who has written a worthy introduction to the `Bella', 1986-87, by Lucian Freud catalogue for the present large-scale and truly impressive exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, names Freud confidently as 'the greatest living realist painter'.

While I cannot disagree with this de- scription, it seems worth pointing out that this has not been a century notable for realist painting. Outside Soviet Russia, where the realist tradition has continued in a form diluted and corrupted by propagan- dist use, and the brief flowering in Ger- many of Neue Sachlichkeit in the Twenties, realism has tended to be the Cinderella movement of 20th-century painting, lan- guishing alone among the ashes while others revel at the Modern Art Ball. Such rejection is hardly surprising, of course, for if modernism can be defined by the degree of its schism with earlier practice, then realism is typified by its self-confessed continuation of a central and long-standing tradition in European art.

It was Herbert Read who made Paul Klee's expression 'not to reflect the visible but to make visible' his personal cut-off point for what was or was not 'modern' in art. By Read's doctrinaire formal stan- dards, Freud, like Balthus, Hopper and Spencer before him, would barely qualify as a modern artist. Yet Freud has generally escaped the opprobrium reserved for for- mal reactionaries within the modem art canon through the apparent pessimism and misanthropy of his approach to human subject matter. It has been a consistent chilliness — which some have seen as the final shortcoming of Freud's art — which has nevertheless redeemed it for mod- ernists and allowed it to nestle, if not exactly at the bosom of modernist ortho- doxy, then at least not in that outer darkness kept for artistic apostates.

In this year's first issue (2 January), I discussed the question of international reactions on the occasion of Freud's first major exhibitions outside Britain. The present Hayward exhibition, which is aug- mented by 17 recent paintings, is a still more impressive event than those which have taken place already in Washington and Paris. Ten years ago, in a public discussion of a book I had written, a fellow critic accused me of seeing myself as 'the one soldier in the company managing to march in step'. At Freud's London opening last week, I could not help wondering how often the artist may have viewed himself similarly during his working life. If, as I believe, significant painting is a supreme conjunction of the activities of hand, head and heart, it is in the latter area that Freud's paintings might have seemed most open to question — thus far, at least. On the other hand, artistic isolation may breed a perverse defiance which places a pre- mium on will-power rather than feeling and a desire to edit out the least evidence of human frailty. At their most embattled, some of the artist's paintings have struck me as even greater triumphs of the will than of artistry. A seeming absence, until recently, of that compassion which char- acterises the works of earlier masters of the realist tradition actually lessens that essen- tial psychological insight which disting- uishes realism from naturalism. Unrelieved bleakness can even tip art towards melo- drama. It strikes me that the sheer re- morselessness of Freud's physical, examina- tion of his sitters may cause the inner person to hide, like pursued quarry, rather than reveal itself. Staring at the mortal envelope does not necessarily make us aware of the spiritual potential within.

While much of 20th-century painting relates only to other art of recent origin, those like Freud who follow the realist tradition join a heritage which stretches back to Giotto and forms the enduring spine of European painting. Although labellers care to see realism beginning , as a historical force, only in the 1840s, there is no doubt that its meaning effectively en- compasses artists who include Van Eyck, Holbein, Breughel, Caravaggio, Velas- quez, Hals, Rembrandt, Vermeer and Chardin, no whit less than Courbet. Simi- lar claims of realism may be advanced for the portraits of Titian, Diirer and others, and for aspects of major artists from predominantly Romantic or neo-Classical periods, such as Goya and Constable. If Giotto's realism may be looked on as an attempt to go beyond the symbolism then current, it is ironic that 600 years later symbolism was seen as supplanting real- ism, while making the very same claim. If, as I have suggested, realism was the solitary form excluded by modernism dur- ing this century, then it has also remained the sole opposed alternative. With the recent so-called demise of modernism, the exiled party has not, however, been re- called to power. For, since the non-stop modernist assault on drawing and other worthwhile traditional practices in art schools, the possibility of a healthy and flourishing alternative has been weakened and well-nigh eradicated. Freud's level of technical achievement has taken decades to develop and may not, therefore — unlike recent, superficial Post-Modernist styles — be assumed overnight like a new hat.

By picking up and measuring himself against the previously pre-eminent Euro- pean tradition, Freud points out, coin- cidentally or otherwise, a more fulfilling future for generations to come.

Previous page

Previous page