Exhibitions

Winifred Nicholson (Tate Gallery, till 2 August)

Gentle reminders

Giles Auty

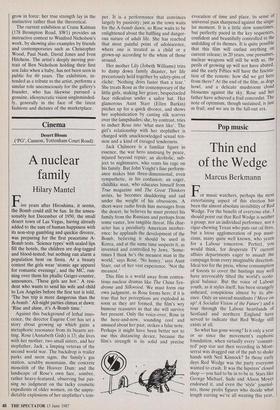

0 urs is an artistic era which confuses the gentle with the ineffectual. In such a climate, the feminine kindness which permeates Winifred Nicholson's radiant images tends to become overlooked and `Moss Roses and White Campanulas at Burwash', c.I937, by Winifred Nicholson, at the Tate undervalued. Today, the more typical artistic voice of womanhood is the macaw shriek of the feminist. By contrast with those who seek only to disparage and dominate men, Winifred Nicholson man- aged to remain, for the rest of her life, on terms of genuine affection with her former husband Ben Nicholson who left her to bring up their three young children, after 12 years of marriage. To her, Ben was an artist of genius and total integrity in his work. This took precedence over personal or family relationships.

Correspondence with her ex-husband, which continued until her death, forms part of the fascinating core of Unknown Colour, a compilation made of Winifred's paintings, letters and writings on art, by her son Andrew Nicholson. This superbly produced new book, published by Faber & Faber, gives invaluable insights not only into its subject's work but into that of Mondrian and of . her ex-husband also. Winifred's artistic approach, from the early Twenties onwards, was to give pride of place to colour, rather than form. In consequence her work often has a clumsy, somewhat incondite look, inviting com- parison with the paintings of Cedric Mor- ris. Both were noted flower painters yet are radically different in the spirit which infuses their work. Where Morris was often theatrical and overbearing, Winifred was humbler but more spiritually intense. Children, flowers and landscape are cen- tral to the range of her subject matter, as they were also to that of Renoir, whose consistently optimistic paintings similarly failed to betray — let alone glory in knowledge of the troubles of this earth. It has always struck me as odd that express- ions of despair or morbid self-pity are respected in visual art when they would not be in life. Conversely, or better still per- versely, expressions of fortitude and optimism have come to be looked down on in art while honoured still in the general processes of living. I suspect those many who now claim to find such satisfaction in the artistic nihilism of others often display little more than evidence of their own immaturity. That Zeitgeist which supposed- ly explains the violence of much recent neo-Expressionist art — and the critical predilections of its apologists — possibly finds its truest form in the behaviour of contemporary football crowds.

Winifred Nicholson grew up in privi- leged circumstances in what was soon to reveal itself as the twilight of an era. During the first world war she made plaster casts in hospitals for soldiers who had lost limbs. After the war, growing social and artistic turbulence created changes which she countered through her inner, rather than worldly, resources. A letter written to the poet Kathleen Raine many years later, during the Sixties, reveals how faith and good humour sustained the artist:

If one says, I can only be happy if I have brandy, or a motor car, or a different lover, or a thousand pounds, or kill my mother-in- law — one is limiting God's working the thing out, and it is just like playing a game of chess, only the white knight may not move on any account. The game of chess will only evolve if all the pieces are in the interplay of the intelligence that has the game in mind from beginning to end.. . .

The show held at the Tate Gallery is the first in London since that put on in 1981 by Andras Kalman, the artist's commercial dealer during the last 25 years of her life. It comprises 60 paintings made between 1922 and 1981 and nine gouaches dating from the artist's experiments in abstraction, 1935-36. Paradoxically, without the framework of observed images, the artist's ideas on colour harmony lose rather than grow in force: her true strength lay in the instinctive rather than the theoretical.

The current exhibition at Crane Kalman (178 Brompton Road, SW1) provides an instructive context to Winifred Nicholson's work, by showing also examples by friends and contemporaries such as Christopher Wood, Paul Nash, David Jones and Ivon Hitchens. The artist's deeply moving por- trait of Ben Nicholson holding their first son Jake when a baby, has not been seen in public for 60 years. The exhibition, in- tended as a tribute to the artist, performs a similar role unconsciously for the gallery's founder, who has likewise pursued a genuine, idiosyncratic vision singleminded- ly, generally in the face of the latest fashions and dictates of the marketplace.

Previous page

Previous page