OUT OF THE GHETTO, INTO THE SUN

Damian Thompson on unease

in the Church about the Archbishop of Canterbury's headline-grabbing

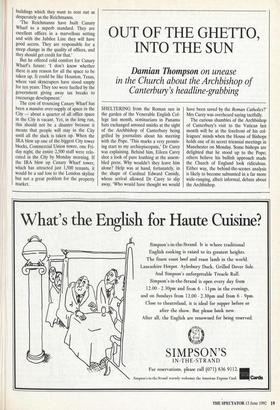

SHELTERING from the Roman sun in the garden of the Venerable English Col- lege last month, seminarians in Panama hats exchanged amused smirks at the sight of the Archbishop of Canterbury being grilled by journalists about his meeting with the Pope. 'This marks a very promis- ing start to my archiepiscopate,' Dr Carey was explaining. Behind him, Eileen Carey shot a look of pure loathing at the assem- bled press. Why wouldn't they leave him alone? Help was at hand, fortunately, in the shape of Cardinal Edward Cassidy, whose arrival allowed Dr Carey to slip away. `Who would have thought we would

have been saved by the Roman Catholics?' Mrs Carey was overheard saying tactfully.

The curious shambles of the Archbishop of Canterbury's visit to the Vatican last month will he at the forefront of his col- leagues' minds when the House of Bishops holds one of its secret triennial meetings in Manchester on Monday. Some bishops are delighted that he stood up to the Pope; others believe his bullish approach made the Church of England look ridiculous. Either way, the behind-the-scenes analysis is likely to become subsumed in a far more wide-ranging, albeit informal, debate about the Archbishop. It is no secret that many of Dr Carey's fellow bishops do not know what to make of him. They like some things about him: his freshness, his sudden enthusiasms and his genuine scholarship. But his unpre- dictability and the slight oddness of his public image bother them. Very few know what he is going to say next: this week's extraordinary swipe at British charities, for example, took them completely by sur- prise. 'Opening the morning paper has become a bit of an ordeal,' one bishop told a colleague. It is a fair bet, though, that most bishops will strike a different note when they run into him on Monday. These things are embarrassing. 'If you go up to him, politeness dictates that you tell him how well he's doing,' says one old hand. 'In any case, he so obviously believes it him- self.'

Dr Carey's new self-confidence was something of a talking-point during his visit to the Vatican. Until recently, he would say things like 'I am the Archbishop of Canterbury' when under pressure, as if he needed to convince himself of the fact. But in Rome, in a purple cassock rather than grey pinstripe, he was clearly luxuriat- ing in the role. (`My God, he's pompous,' gasped one correspondent.) On the Sun- day, celebrating a sung eucharist in All Saints' Anglican Church, it was hard to believe he had ever been the plainest of

evangelicals. 'I bet he won't know what to do,' whispered a colleague as Dr Carey strode onto the sanctuary. Then the Pri- mate's hands emerged from his old-fash- ioned Gothic chasuble and he crossed himself reverently. 'He's learning,' mut- tered my companion.

Is he? It would be a mistake to assume that Dr Carey is on the verge of losing his unsophisticated image, or even that he wants to. A jovial clergyman at a drinks party in All Saints' garden outlined his theory. 'The Careys have lived their lives in an evangelical ghetto from which they've suddenly emerged, blinking in the sunlight,' he explained. 'The Archbishop has discovered that he rather likes the trappings of the job. But deep down he will always be suspicious of people from outside that world.' Mrs Carey, he thought, was more evangelical than her husband, and wielded considerable influ- ence. 'Not a Mrs Proudie, perhaps, but maybe a Mrs Kinnock.'

In one respect, certainly, it is a good analogy. Eileen Carey, like Glenys Kin- nock, is an ideological purist who dislikes the media even more than her husband does. It was she, it is rumoured, who dur- ing the last York Synod persuaded him to stride up to a journalist and tell him, 'I want you to know how deeply I resent the tone of your article.' Dr Carey has a sur- prisingly hot temper, it is true, but there was more to it than that: both he and his wife take the evangelical line that criticism of a Church leader is impertinent, tanta- mount to an attack on Christianity. In the early days, even Lambeth Palace's evan- gelical press office took this lofty view, asking journalists what role God played in their work. That is now beginning to change. Dr Carey may dislike the media, but as he gains in confidence he is learning to exploit what he would call its 'evangelis- ing potential'. He would not admit it, but his pronouncements on over-paid busi- nessmen and the pill were framed with an eye to the tabloids. It is worth remember- ing that his first ever national newspaper interview, before he got his fingers burnt and broke off relations with the press, was with the Sun.

No one is suggesting that George Carey

is an admirer of the Sun (though he could learn a lot from its economy of style). But Sun-readers are the great unchurched, to whom he wants to speak, like a good evan- gelical, above the heads of the establish- ment. And they seem to be listening: on the subjects of the pill and the Pope, the Archbishop struck a chord in every saloon bar in the land. What is there to lose?

The answer depends on the importance Dr Carey places on the good opinion not only of his senior colleagues, but of the Church. In the past months, observers have become aware of a general unease in the upper reaches of the Church of England. The confusion felt by some of the more experienced bishops, in particular, is grow- ing by the week. It puzzles them, for exam- ple, that a supposedly evangelical arch- bishop spends all his time paying tribute to the 'richness of Catholic spirituality' and yet seems to have no understanding of the nature of authority in the Church. They are disturbed by the extreme contrast between his elegant sermons on abstruse philosophi- cal matters (all his own work, he says) and the rambling worthiness of his live inter- views. They are irritated by his habit of pre- senting his own views, notably on women priests, as those of the Anglican Commu- nion. And there is a general feeling among them that Lambeth does not really care what they think.

Most of all, they are alarmed that they cannot make out a George Carey philoso- phy, a coherent strategy for the revival of an ailing Church of the sort outlined by the Bishop of London this week. Some senior bishops believe that there is an oppor- tunism about the Archbishop's choice of themes which is confusing and demoralis- ing the very people whose support the Church most needs: intelligent clergy and churchgoers who feel insulted by Dr Carey's new enthusiasm for headline-grab- bing. Not all bishops have come to this con- clusion, obviously, but those who have are profoundly worried. They may not discuss their fears with the Archbishop on Mon- day, but he should be aware of them all the same.

Damian Thompson is religious affairs corre- spondent of the Daily Telegraph.

'You wait ages for a cliche, then three come along at once.'

Previous page

Previous page