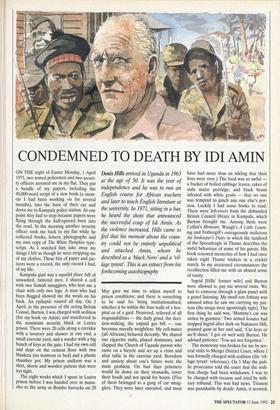

CONDEMNED TO DEATH BY IDI AMIN

ON THE night of Easter Monday, 1 April 1975, two armed policemen and two securi- ty officers arrested me in my flat. They put a bundle of my papers, including the 40,000-word script of a new book (a mem- oir I had been working on for several months), into the boot of their car and drove me to Kampala police station. At one point they had to stop because papers were flying through the half-opened boot into the road. In the morning another security officer took me back to my flat while he collected books, letters, photographs and my own copy of The White Pumpkin type- script. As I watched him take away my things I felt as though he were stripping me of my clothes. Those bits of paper and pic- tures were a record, the only record I had, of my life.

Kampala gaol was a squalid place full of unwashed, tattered men. I shared a cell with two Somali smugglers, who lent me a chair with only two legs. A man who had been flogged showed me the weals on his back. An epileptic roared all day. On 3 April, in the presence of the acting British Consul, Burton, I was charged with sedition (for my book on Amin) and transferred to the maximum security block at Luzira prison. There were 20 cells along a corridor with a lavatory and shower at one end, a small exercise yard, and a warder with a big bunch of keys at the gate. I had my own cell and slept on the cement floor with two blankets (no mattress or bed) and a plastic chamber pot. My prison uniform was a shirt, shorts and wooden pattens that were too tight.

The eight weeks which I spent in Luzira prison before I was handed over in mana- cles to the army at Bombo barracks on 29 May gave me time to adjust myself to prison conditions; and there is something to be said for being institutionalised, whether it be within the four walls of a hos- pital or of a gaol. Neutered, relieved of all responsibilities — the daily grind, the deci- sion-making, the unpaid gas bill — one becomes morally weightless. My cell-mates (all Africans) behaved decently. We shared our cigarette stubs, played dominoes, and clapped the Church of Uganda parson who came on a bicycle and set up a cross and altar table in the exercise yard. Boredom and anxiety about one's future were the main problem. On bad days prisoners would lie down on their stomachs, cover their heads and not speak for hours. (Five of them belonged to a gang of car smug- glers. They were later executed, and must have had more than an inkling that their lives were over.) The food was so awful a bucket of boiled cabbage leaves, cakes of stale maize porridge, and black beans infested with white grubs — that no one was tempted to pinch any one else's por- tion. Luckily I had some books to read. These were left-overs from the disbanded British Council library in Kampala, which Burton brought me. Among them were Cellini's Memoirs, Waugh's A Little Learn- ing and Fothergill's outrageously malicious An Innkeeper's Diary in which the landlord of the Spreadeagle in Thame describes the awful behaviour of some of his guests. His book renewed memories of how I had once taken eight Thame wickets in a cricket match. In my straitened circumstances the recollection filled me with an absurd sense of vanity.

Ingrid [Hills' former wife] and Burton were allowed to pay me several visits. We had to converse through a glass panel with a guard listening. My small son Johnny was amused when he saw me carrying my pat- tens (the straps were agonisingly tight). The first thing he said was, 'Mummy's car was stolen by gunmen.' Two armed kondos had stopped Ingrid after dark on Nakasero Hill, pointed guns at her and said, 'Car keys or we'll shoot.' I got on well with Burton. He advised patience: 'You are not forgotten.'

The monotony was broken for me by sev- eral visits to Mengo District Court, where I was formally charged with sedition (the 'vil- lage tyrant' reference). On 5 May the pub- lic prosecutor told the court that the sedi- tion charge had been withdrawn. I was to be charged with treason and tried by mili- tary tribunal. This was bad news. Treason was punishable by death: Amin, it seemed, was determined to get me. On 25 May I was manacled and, with an escort of two army officers and ten armed soldiers, hand- ed over to Malire Special Mechanised Reconnaissance Battalion at Bombo bar- racks. 'You are a very dangerous man,' said the officer who took me to the guard room. Here soldiers threw me to the ground, tore my clothes and tried to force a second pair of handcuffs over my wrists. When they had gone I lay down on the cement floor of my cell to think things over. Someone had writ- ten on the wall, 'I shall not see again this world'. Whatever I did, I knew that I must retain my dignity (soldiers despise cowards) and avoid upsetting the guards (who might be half drunk). I noticed a long nail sticking in the cell door. If my situation became unbearable I could cut my wrist with it. I played with the thought for a minute or two, then rejected it. Wrist-cutting would be shameful.

Lieutenant-Colonel Sule, the Battalion Commander, removed my handcuffs in the morning and I felt I could relax. Ten men with Kalashnikovs guarded me, another section sat in the guard room at the end of the corridor (all the cells except mine were kept empty). The latrine was a nasty hole in the floor. Soldiers stood over me when I used it. I was handed an amended copy of the charge sheet to brood over and a few days later, on 9 June, given ten minutes to wash and hurried to the courtroom. My

escort officer wore the glengarry and kilt of one of Amin's show units CI respect the Scots. They are better and braver than the English').

The trial, which lasted three days, was a sinister farce. The chairman of the tribune was a ferret-faced major, a promoted thug who didn't know English and was Amin's mouthpiece. The other four members were junior officers and mere passengers. All carried ceremonial swords. The proceed- ings were in English and Swahili. When Mr Wilkinson, who had agreed to defend me, entered the room the chairman said he had no right to be there and dismissed him. The last of the prosecution witnesses to be called was Ingrid. The prosecuting officer, a captain, as part of his tactics to discredit my relationship with Ingrid, had already referred to her as my 'former wife' (bibi zamani), and I had protested. Ingrid told the tribunal that in law a wife could not be made to give evidence against her husband, and that she would not do so. The chair- man gave her a nasty look and said one word, `Kwenda!' (Go away!).

There were some awkward moments. I had called Amin a 'black Nero' as well as a `village tyrant'. 'Who is this Nero?' asked the chairman. 'The cruellest of all the Roman emperors,' explained the prosecut- ing captain. The courtroom went silent and I looked through the window. But it was the reference in my text to 'spies' that the prosecutor seized on. Here is the passage: -

Amin is fond of calling us 'spies' (a white man seen bird-watching in a sugar-cane field or changing a wheel within a mile or two of a barracks had better watch out); and though the European bridles at the charge, there is some truth in it, for we foreign residents, whether we like it or not, are the eyes and ears of a wider world. Our presence in Ugan- da must have some inhibiting effect on the excesses of government. The African feels less isolated and less vulnerable while there are white faces around. Corpses may be dumped in swamps, individuals disappear. But the word spreads. It reaches the news media, and a Nairobi or a London newspa- per, though they may not always get the facts right, will announce their obituaries.

The prosecuting officer picked out a sin- gle phrase without its context, and misquot- ed it (`Amin calls us spies, and there is truth in it'), but it was enough for him to charge me and the British community with widespread espionage activities in Uganda. My book was deliberately intended to harm the Uganda government, which was trea- son; and I was a spy. By the time I had made my own address — no doubt to the ears of those imposters it must have sound- ed priggish CI have written what I believe is true') — the tribunal had had enough. 'Words,' exclaimed the chairman, 'words, many, many words.'

My appearance in the courtroom next morning was brief. 'You have bad eyes,' said the chairman, 'a bad look in your eyes.' The verdict was guilty. I was taken out, and brought back to hear the sentence: to be shot by firing squad. The five officers then sheathed their swords and I was left among the scattered papers. I could see my type- writer, which had been produced as evi- dence, on a desk with its ribbon broken. It was an old-fashioned Remington given to me as a schoolboy and I would not see it again. I had no feeling of shock. The tri- bunal had shown itself so unsympathetic that the death sentence was not unexpect- ed; and a firing squad was better than being hanged. A kilted sergeant and guards with fixed bayonets took me back to my cell.

This was a painful moment, and I remem- ber it clearly. Sun and shadow had cast a blue haze over the green valley below Bombo. Outside the thatched huts smoke was spiralling from cooking fires where

women were preparing matoke and chil- dren chivvying livestock. For 12 years I had lived among these people as a friend. Now I was an enemy, and soldiers were hustling me away like a goat.

Diplomacy saved Hills. The Queen wrote a letter, Hills officially expressed his regret, James Callaghan, then Foreign Secretary, flew out in person to escort him home. The White Pumpkin was published with only four words, 'like a village tyrant, omitted.

Previous page

Previous page