Exhibitions 1

What is he up to?

Martin Gayford

What is Lucian Freud up to? We know, of course, that he is among the most celebrated painters alive. He may well also be — though, naturally opinions are divid- ed — among the greatest (there are other candidates, Jasper Johns and Balthus among them, but not many). The small display which he has just mounted at the Tate Gallery is a remarkable manifestation of continuing creative power and audacity in an artist now in his mid-Seventies.

There are surprises, new departures, some magnificent paintings, some near- misses. But as a whole, there is no doubt about it, this is a tour de force. Indeed, it is all the more so because it is presented almost casually — not a show, but a 'show- ing', just a few recent works, and of those, not all the best. In a typically grand, dandyish gesture, Freud has. omitted per- haps the most spectacular paintings he has executed in the past few years, those of the mountainous model known as Big Sue.

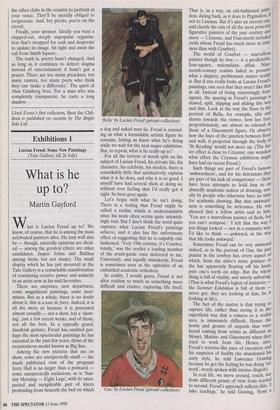

Among the new pictures that are on show, some are unexpectedly small — the much publicised view of the pregnant Jerry Hall is no larger than a postcard some unexpectedly audacious, as is 'Sun- day Morning — Eight Legs', with its unex- pected and inexplicable pair of knees protruding from beneath the bed on which `Bella' by Lucian Freud (private collection) a dog and naked man lie. Freud is remind- ing us what a formidable artistic figure he remains, letting us know what he's doing while we wait for the next major exhibition. But, to repeat, what is he really up to? For all the torrent of words spilt on the subject of Lucian Freud, his private life, his character, his celebrity, his models, there is remarkably little that satisfactorily explains what it is he does, and why it is so good. I myself have had several shots at doing so, without ever feeling that I'd really got it right. So here goes again.

Let's begin with what he isn't doing. There is a feeling that Freud might be called a realist, which is understandable since his work often seems quite astonish- ingly real. But I don't think the word quite captures what Lucian Freud's paintings achieve, and it also has the unfortunate effect of suggesting that he is culpably old- fashioned. 'Very 19th century, it's Courbet, totally,' was the verdict a leading member of the avant-garde once delivered to me. Conversely, and equally mistakenly, Freud is sometimes seen as the upholder of an embattled academic orthodoxy. In reality, I would guess, Freud is not after realism so much as something more difficult and elusive: capturing life itself.

`Gaz' by Lucian Freud (private collection) That is, in a way, an old-fashioned ambi- tion, dating back, as it does to Pygmalion, if not to Lascaux. But it's also an eternal one, and clearly the aim of all the most powerful figurative painters of the past century and more — Cezanne, and Giacometti included (with whom Freud has much more in com- mon than with Courbet). The world of Courbet — marvellous painter though he was — is a predictable, four-square, rationalistic affair. Nine- teenth-century realists failed to perceive what a slippery, problematic matter reality is. But if one really looks at Lucian Freud's paintings, one sees that they aren't like that at all. Instead of being reassuringly four- square, the spacing in Freud's paintings is slewed, split, slipping and sliding this way and that. Look at the way the floor in the portrait of Bella, for example, tilts and shoots towards the viewer, how her feet, proportionately, are almost as colossal as those of a Giacometti figure. Or observe how the lines of the junction between floor and wall, if projected through the body of lb Reading' would not meet up. (The lat- ter effect is close to Cezanne; one wonders what effect the Cezanne exhibition might have had on recent Freud.) Such things are part of Freud's famous `awkwardness', and for his detractors they are part of his lack of competence — there have been attempts to hold him to an absurdly academic notion of drawing, usu- ally by people who otherwise have no time for academic drawing. But that awkward- ness is something he welcomes. He was pleased that a fellow artist said to him, `You are a marvellous painter of flesh, but you can't compose.' I felt that the way I put things looked — not in a romantic way, I'd like to think — awkward, in the way that life looks awkward.'

Sometimes Freud can be very awkward indeed, as in the portrait of Gaz, the jazz pianist in the cowboy hat, every aspect of which, from the sitter's tense grimace to the hat apparently floating off his head, puts one's teeth on edge. But the whole thing is full of vitality, and utterly unboring- (That is what Freud's legion of imitators — the Summer Exhibition is full of them — never get; they are looking at him, he is looking at life).

The fact of the matter is that trying to capture life, rather than seeing it in the superficial way that a camera or a realist sees, is immensely difficult. Hence the howls and groans of anguish that were heard coming from artists as different as Monet, Matisse and Giacometti when they tried to work from life. Hence, also, Freud's tortoise-like pace of execution and his suspicion of facility (he abandoned his early style, he told Lawrence Gowing because he got the feeling he was doing 'art work', words spoken with intense disgust). In real life, we move around, touch, see from different points of view from second to second. Freud's approach reflects this. I take readings,' he told Gowing, 'from a number of positions because I don't want to miss anything that could be of use to me. I often put in what is round the corner from where I see it, in case it is of use to Me. It soon disappears if it is not. Towards the end I am trying to get rid of absolutely everything I can do without. Ears have dis- appeared before now.' The awkward truth- fulness of Freudian space may derive from his working method. It sounds as if, some- times at least, he is melding together differ- ent viewpoints. So much for realism. Trying to paint life also means capturing, so to speak, the spiritual vibrations of the subject. 'You are very conscious,' he has said, 'of the air going round people in dif- ferent ways, to do with their particular Vitality.' This might seem mystical mumbo- Jumbo, but you can see exactly what he means by comparing the portraits of Gaz, who seems nervously, perhaps aggressively, weary, with Tristram Powell, wary and .

It has been alleged that all Freudian sub- jects end up the same, victimised by his marathon sitting-sessions, sodden with exhaustion brutally stripped bare. This isn't so either. What his sitters are stripped of is the banality of conventional expecta- tions. That is why the nudes in particular can initially seem shocking. But the shock wears off, and then it's possible to recog- nise that Freud's people are seen without the superficial social facade, as what they essentially are — vulnerable, often melan- choly — but with more, not less, human ulgnitY. This is an achievement worthy of his enormous reputation.

Previous page

Previous page