A real capital

Henry Fairlie

Washington There is an important point to make about the presidential election. I can best make It with two vignettes.

Last Friday, I was invited to join a

dinner in Washington for none other than our own Professor Hugh Trevor-Roper, and his Lady Alexandra. I suppose that American newspapers might describe Mr Trevor-Roper as the 'ranking historian' from Oxford. And then, as if there can be 110 end to the richness of life to which common people may aspire, Lady Alexandra and Mr Trevor-Roper were again my dinner companions on Saturday, and 1 at last went to bed satiated with the kind of talk which I have long forgotten.

I woke on Sunday, feeling that enough is

enough, when lo and behold! the Literary Editor of the Washington Post asked me to .1°10 a lunch for none other than our own br J. H. Plumb, whom American newspapers might as well describe as the ranking historian' from Cambridge.

It was with a certain glee of mischief, Perhaps caught from Christ Church, that I dropped into the ear of Dr Plumb the fact that Mr Trevor-Roper was also in town.

Imost—but not quite—at once, the biographer of Robert Walpole asked me Where the biographer of Archbishop Laud Was staying; and when I told him, Cambridge responded with an ineffable affability to Oxford's pretensions: 'Of course, I was called down here by the Ambassador, you know. . . huh?'

Satiation had by now given way to

common greed, and I hung around the telephone on Sunday evening, certain that someone would call me and say that A. j. P. Taylor was here doing a television Programme, or that Lord Macaulay had dropped in.

„_The point of this story is that it is about Washington, and that the coincidence of both visits of the two great historians was °oth surprising and not surprising. The ,,Greeks had come to Rome, but then the Greeks these days are always coming to lkome. 'Hi! Diogenes!' one is always saYing, 'What's brought you here?' And 1)logenes replies that he has come to teach rhetoric to the sons of the Roman senators. . Washington is becoming a real capital— IS Possibly even on the way to becoming a great capital—and why this matters is that it helps, to put in place the trendy talk hat the American people are 'against washington'. The two candidates who are most Obviously running 'against Washington' are the representatives of the extreme right Wing in each of the parties: Ronald Reagan

and George Wallace. It appears to some that their rhetoric has touched the other candidates, especially Jimmy Carter, of whom one sometimes feels—not always, but sometimes—that he could be fitted with any smiling ideology as with any smiling dentures. It is important, therefore, to understand what the rhetoric means. It is important also because in England and Europe, in the western world of which America is now the leader, there appears also to be a fashionable reaction against 'big government', and on this America may again teach.

Again ? Let us not forget that, faced with Mussolini and Stalin and then Hitler, after his election in 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the one formidable and needed demonstration that democracy can govern and succour its own people in a crisis. As soon as he took office in 1933, he proved that government in a free society could work. He did it—and no one else. No one else, that is, except the Americans who elected him, and then supported him. Since the West is now obviously in the same kind of trouble that it was in in 1933, it is worth attending very carefully—and not slyly, or mischievously—to what the American election will tell us.

In many ways, and at many levels, the issue is already alive, in the electors and in the politicians, and as they develop it, I presume that in the next months there will be much to say about it : whether a government should be allowed to have its own secrets, whether a government of a great power should be allowed to maintain an efficient and resourceful secret service . . . and so on.

But it seems to me important to establish, first, that Washington has become a very different place from what it was ten years ago. There is the smell of a real capital about it now, and it's very'strange to grasp.

Until now, the United States has had two capitals: its commercial and cultural capital in New York, its political capital in Washington. The genius of New York is dispersing what a great and brilliant city New York has been—everyone knows it— and that greatness and brilliance will not fade easily. But the genius of New York has begun to wither, and Washington is stepping forward to take its place.

It is difficult to put one's finger on the point in a hurry, in one column, and I hope to explore and develop it, because it is fundamental: that not only America, but the western world as such, is about to have a real capital again: a real, exciting capital, but still with the size of a genuine political city in the past.

The news from the provinces is very interesting—from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Florida, Illinois, even New York itself at the beginning of April—but it is news that is now more immediately directed to Washington than ever before. Even George Wallace says: 'Send a message to Washington, to tell Washington to reduce its power'. And that is a phoney message, if it is only Washington that can reduce Washington. The whole idea of redistributing power from the Federal Government to the States is similarly phoney, because it is a redistribution at Washington's command.

The Florida results confirm my prediction last week that the most remarkable immediate feature of this election will be the early elimination of the extreme right-wing candidates in both parties. President Ford is now all but impregnable and not only against Ronald Reagan but against any other corner. George Wallace's campaign has now suffered a very severe setback from which it is hard to believe that he can recover. But beyond the Florida primary something is already taking place in this election: a reflective assertion by the American people, through their candidates, that they cannot stamp their feet, like spoiled children, and say that they will not be a Great Power, with all that means.

They are standing up for government, in their own complicated way: not just sending one 'message' to Washington, as George Wallace would have them do, but sending a series of qualifying but not contradictory cables.

They are searching out—'the people' are, in that strange way in which 'the people' do exist—their own answers to 'bigness': to 'big' government, 'big' unions, 'big' corporations—and they are not panicking. It would be so easy for them to run away, to pretend that America is not a 'big' power, and that 'bigness' is a part of modern life. But however tempted, they will not do it.

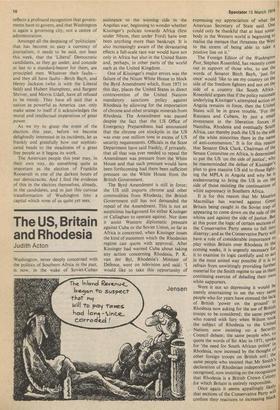

A lot of the rhetoric that is summed up in the words, 'against Washington' reflects a genuine dissatisfaction with unnecessary and inefficient government—but it also reflects a profound recognition that governments have to govern, and that Washington is again a governing city, not a centre of administration.

Amongst all the despising of `politicians' that has become so easy a currency of journalism, it needs to be said, not least this week, that the 'Liberal' Democratic candidates, as they go under, and concede at last to a standard-bearer for them, are principled men. Whatever their faults— and they all have faults—Birch Bayh, and Henry Jackson (who is with the Liberal field) and Hubert Humphrey, and Sargent Shriver, and Morris Udall, have all refused to be trendy. They have all said that a nation as powerful as America can only make sense to itself if it acknowledges the moral and intellectual imperatives of great power.

As we try to grasp the event of the election this year, before we become delightedly interested in its incidents, let us frankly and gratefully bow our sophisticated heads to the steadiness of a great free people as it begins its work.

The American people this year may, in their own way, do something quite as important as the election of Franklin Roosevelt in one of the darkest hours of our democracies. And I find the evidence of this in the electors themselves, already, in the candidates, and in just this curious transformation of Washington into a capital which none of us quite yet sees.

Previous page

Previous page